On Sunday night Ulay, born Frank Uwe Laysiepen, died from cancer. Out of this illness, with which he was diagnosed in 2011, came a piece of art: the film Project Cancer (2013), which can be considered in retrospect as one of his defining works, although Ulay always opposed the idea of a recognisable ‘signature style’. Through his work – and his work was his life, and vice versa – Ulay always fought against himself; that is, against the idea of a fixed, and socially determined and accepted, identity.

From the early 1970s, Ulay mostly appeared in front of his polaroid camera to create what he called Auto-Polaroids, photographic stories of, for example, a transgender person or a person who is half a man, half a woman. One of his early performances, which immediately overwhelmed me when I first saw a video of it a few years ago, was titled Fototot (photo death). The performance (one of two with the same title) took place in 1976 in a then-famous gallery for performance art called Galerie Beyer in the German city of Wuppertal. Ulay was naked and handcuffed. A long mirror leaned against his front and stood there until he fell forward with exhaustion and the mirror shattered under his body on the floor. There was this raw energy combined with conceptual ideas about perception and imagery and a concern for human ethics, which I had never seen before. One of the many axioms that Ulay often created spontaneously was: ‘Aesthetics without ethics is cosmetics.’

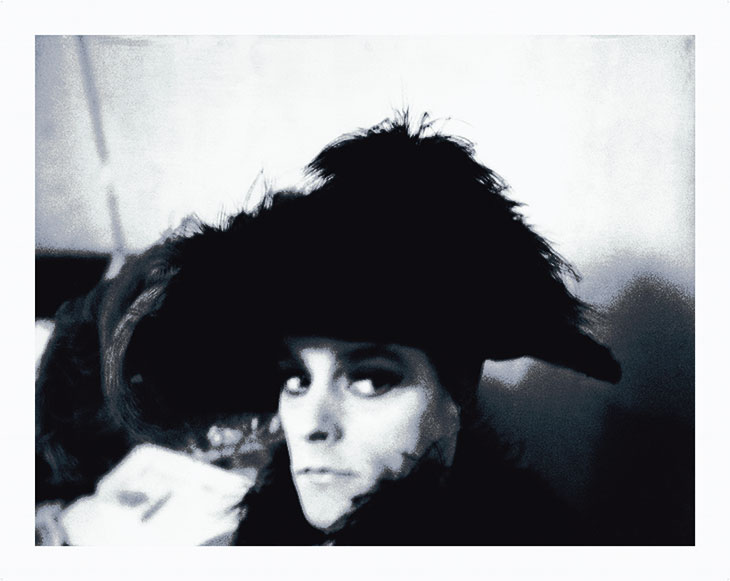

S’he (1973), Ulay. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London; © Ulay

His first really well-known work, before he stepped into his famous romantic and artistic collaboration with Marina Abramović, has its beginnings in Berlin, also in 1976, when he visited the Neue Nationalgalerie and spotted Der arme Poet (The Poor Poet) by Carl Spitzweg, who was one of Adolf Hitler’s favourite artists. Ulay’s intervention, which took place a few days after his visit, would become one of the most-discussed art thefts in the world. He entered the Neue Nationalgalerie, cut the painting loose from its hanging device and ran out of the museum with the painting underneath his arm, followed by security guards. He then entered his car, parked at the back of the building, and escaped with the painting to the neighbourhood of Kreuzberg, which at that time was the home of many so-called Gastarbeiter (immigrant workers). In the apartment of a Turkish family Ulay then replaced one of the family’s own works with the Carl Spitzweg painting. Finally, Ulay called the police and let them know where they could find the stolen canvas.

The years between 1976 and 1988 are recognised as the years of the symbiotic couple Abramović/Ulay. Already in 1974 Ulay had made a work in the vein of a suicide note, which announced Mein Abschied als einzige Person (My Farewell as a Single Man). What earlier had been the battle against his own self did not, I think, radically change when he was with Marina Abramović. Rather, it was expanded – as he viewed himself through the alter ego that Abramović became, which can of course be understood the other way round as well. Whether they would alternately hit each other’s faces with their bare hands or take turns shouting at each other – the performances always ended when one of the two decided to stop. The way the partners acted went beyond stereotypes of partnership: it stressed the power of humanity, of believing in another person, to move mountains.

Sex-stretcher (1974), Ulay. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London; © Ulay

I am still very proud of his first significant retrospective, which I curated with him in 2016 at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. To work with him was a great gift – always a lot of fun, always with his wonderful wife Lena, always with good food and good wine, and the show would not have come about in time if I had finished listening to all the anecdotes and stories that he shared for every single work in his archive in Ljubljana. He laughed out loud when I read from his so-called ‘aphorisms’ when we met once in his small apartment in Amsterdam. These aphorisms – which were obviously influenced by Samuel Beckett, the most important writer in the world for Ulay, who had a large collection of the writer’s first editions – were largely typewritten in German around 1968, when he was just leaving his home country for Amsterdam. One of the aphorisms written in English is simply: ‘nice-to-be’.