In September of 2017, following a summer in which debate regarding confederate statues swelled, Bill de Blasio, the mayor of New York, announced the establishment of an advisory commission on the city’s art, monuments and markers. A board comprising a diverse panel of sociologists, architects, anthropologists and historians would take into consideration each of New York’s public artworks and review them on a case-by-case basis. The general public were also invited to share their views, through an online survey and in person during public hearings. The advisory commission was not intended to discuss entire removal of any monument, but to consider their context and placements within the city.

The commission’s report was released in January of this year. It does not offer concrete answers, but identifies a set of guiding principles to use as a framework for evaluating monuments in future, and openly deliberates on the merits of action versus inaction: ‘Monuments and markers are nearly always political in nature, and thus actions relating to existing monuments and markers (including a decision to take no action) are similarly political gestures.’ The report puts forward recommendations for four monuments, ranging from the suggested fabrication of new pedestals and informative plaques to the possibility of relocating statues to less prominent locations – although opinion within the report was divided on the latter idea. These nuanced discussions and lack of consensus not only indicate the complex histories that pertain to these markers in particular, but also contribute to a more general discussion about our expectations for public artworks, both old and new.

Human Nature (2013), Ugo Rondinone. Rockefeller Center. Photo: James Ewing; courtesy Public Art Fund, NY

The exhibition ‘Art in the Open: 50 Years of Public Art in New York’ at the Museum of the City of New York, then, is timely. The advent of the show is not in fact associated with the mayoral commission, but rather the 40th anniversary of the Public Art Fund, an organisation responsible for many of New York’s best loved and most challenging public art commissions, from Rachel Whiteread’s shimmering resin Water Tower, perched on a SoHo rooftop, to Ugo Rondinone’s Human Nature at the Rockefeller Center.

The introductory half of the exhibition takes the form of a dense, informative timeline, which stretches back past the Public Art Fund’s formation in 1977, to the 1960s. It was this decade that saw attitudes towards public art shift. The established tradition of commemorative memorials or decorative sculptures tied within architectural design gave way to a practice of commissioning contemporary works intended to show the city’s cultural prowess to the world, reinvigorate underused areas and pull art from the confines of institutions.

We learn of the first major outdoor exhibition ‘Sculpture in Environment’ organised by the Parks Department in 1967, which saw Claes Oldenburg digging a grave in Central Park, and the formation in 1969 of City Walls Inc. by Doris Freedman, the Grand Dame of New York public art commissioning – a project initiated to use and brighten the proliferation of walls of half-demolished buildings in the city, as the optimistic boom of the 1960s slid into the recessive ’70s. City Walls Inc. would later merge with the Public Arts Council, founded in 1972 (also by Freedman), to become the Public Art Fund as we know it today.

Keith Haring’s Untitled (Three Dancing Figures) (left) and Yellow Arching Figure (right) installed at Doris C. Freedman Plaza, New York in 1997. Photo: Frederick Charles; courtesy Public Art Fund, NY

The text-heavy nature of this timeline may prove a turn-off to some viewers, but the volume of information provided is justified in order to address its sprawling subject, and it is supported by images, a short video documentary, and jaunty stickers urging us to ‘Go See’ permanent works throughout the city. The timeline speaks not only of great public artwork successes, but also its failures, most famously the removal of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc in 1989 after eight years of acrimonious opposition, circumstances exemplifying the risks of commissioning public artworks that neglect to take into account their audience and environment. (Serra’s sculpture is also the only contemporary work cited in the advisory commission’s recently published report.)

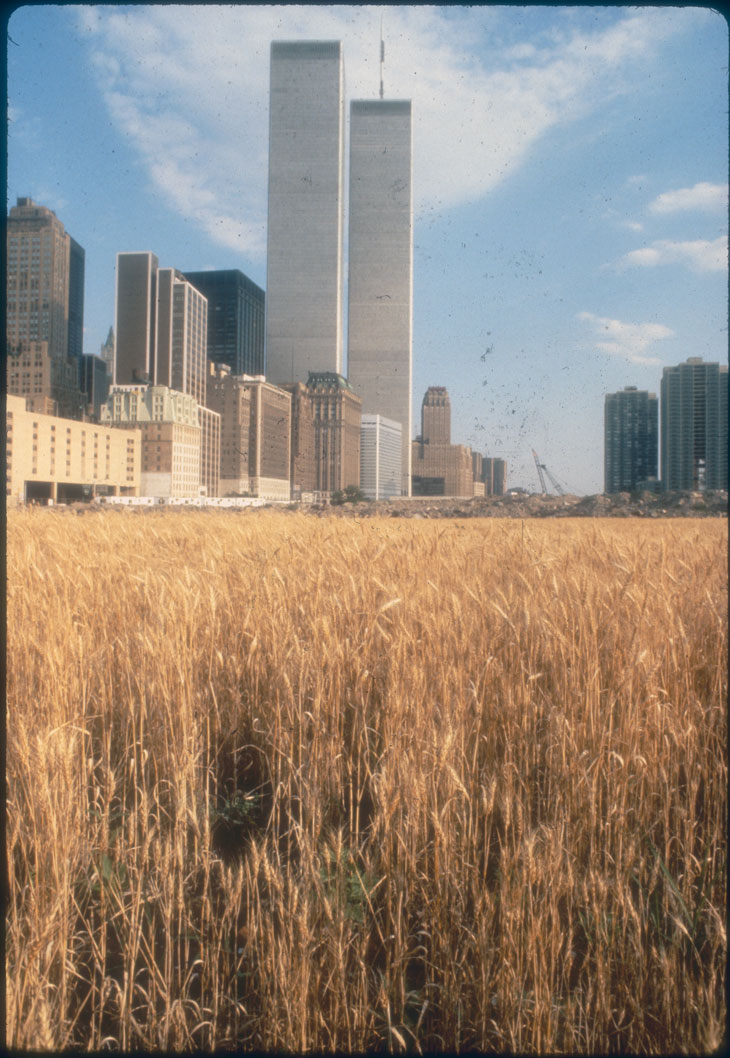

The second half of the exhibition presents displays with ephemera from key projects highlighted in the preceding timeline, and contextualises the development of ‘site-specific’ and socially minded public artworks. There is the site plan from Agnes Denes’s Wheatfield: A Confrontation (1982), which occupied Battery Park’s landfill site and acted as a powerful critique of the values of world trade as represented by the neighbouring Twin Towers; and one of Kara Walker’s sugar-coated boy sculptures from her installation A Subtlety, which held court in the shell of Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar factory in 2014. Other notable highlights include a video and maquette from Bill Brand’s extraordinary work Masstransiscope (1980), restored to full glory in 2008, which transforms a Brooklyn subway tunnel into a zoetrope as trains zip through, and Keith Haring’s fingerprint identification card – from one of his many arrests for tagging offences before his murals became some of New York’s most iconic artworks.

Wheatfields for Manhattan (1982), Agnes Denes. Battery Park City landfill. Photo: Donna Svennevik; courtesy Public Art Fund, NY

‘Art in the Open’ offers valuable insight into the journey an artwork goes through in order to reach public space, as well as the figures behind the organisations (many of them women) that have enabled such projects to happen over the last four decades. Perhaps more importantly, it asks us to consider what exactly makes a public artwork successful. As Kendal Henry (current director of New York’s Percent For Art public art programme) notes in the exhibition documentary, in early years this was predominantly measured by whether an artwork physically lasted for the intended duration of its installation. Now there are many, more subjective, criteria to consider, such as whether the artwork is embraced by, and fully inclusive of, the community it inhabits. Does it draw people to a different neighbourhood, generate conversation, or alter our urban experience in some way? No doubt, there are also the statistics of visitor numbers and tourism generated by large-scale projects, factors as much about keeping New York a frontrunner in culture now as over 40 years ago.

While the city continues to wrestle with how to handle its controversial historic monuments, ‘Art in The Open’ makes a powerful case for the legacy of New York’s contemporary public art programme – one that continues to grow, suffusing, rubbing against, and contributing to ever-evolving dialogues across the city.

‘Art in the Open: 50 Years of Public Art in New York’ is at the Museum of the City of New York, until 13 May.