When I listen again to my conversation with Giorgio Griffa, recorded at his studio in Turin last November, I am struck by its prominent soundtrack. Strains of Prokofiev and Mozart fill any pauses, as though the interview were taking place backstage at an orchestral concert. At one point, something more brassy and baroque sounds across the words – familiar to me in its rhythm, if not directly identifiable.

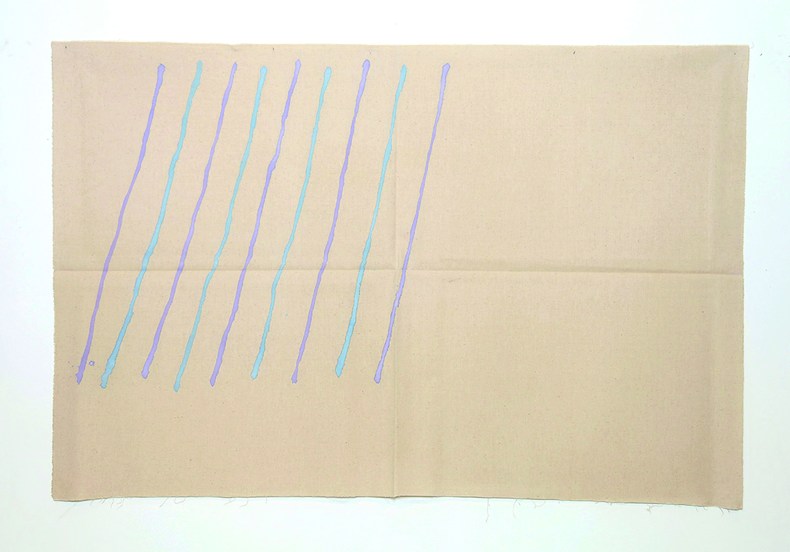

This accompaniment is entirely appropriate, since music – which plays continuously in the studio – has long been key to Griffa’s thinking about art and his own artistic process. For him, rhythm sits at the root of human experience and creativity. ‘Fundamentally, music, poetry, and painting have all worked with the first element of human knowledge, which is rhythm’ he tells me, ‘the rhythm of sowing and harvesting, the rhythm of the sun, of day and night.’ To anyone who knows his spare, if inadvertently lyrical paintings, which have sometimes been compared to musical scores, this will come as no surprise: these are works that find a visual form for rhythm – for the rhythm of their own making – in their ostensibly simple repeated marks, often applied to the canvas with a brush or sponge at set intervals.

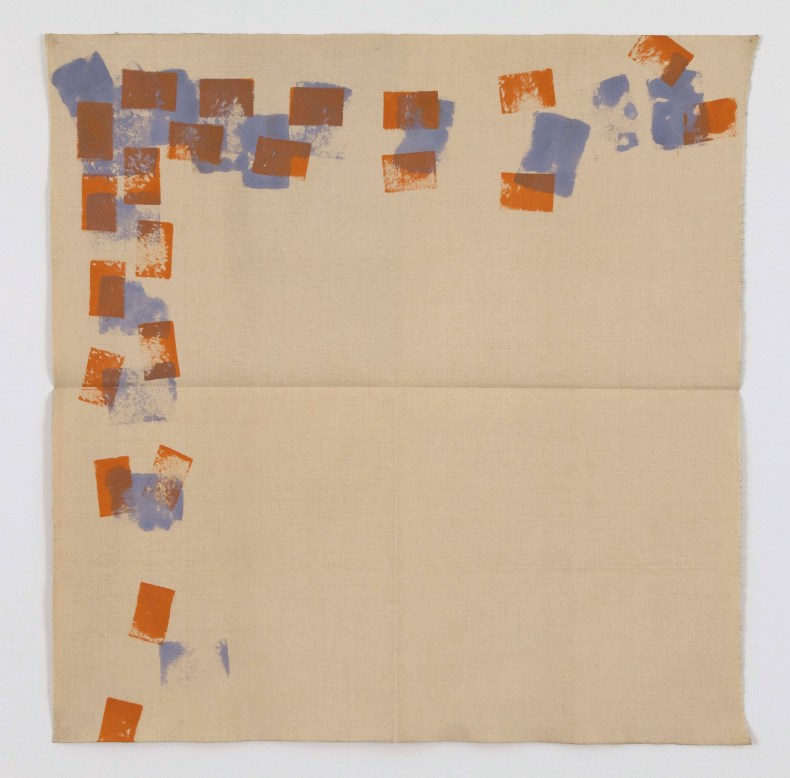

Spugne (1969), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Giulio Caresio; courtesy Archivio Giorgio Griffa

Griffa has been painting in his distinctive manner for five decades, creating an unusually consistent body of work that continues to ask questions about the relationship between painting and knowledge. Although his work is less well known internationally than that of some of his Torinese contemporaries, it is now having its institutional moment – ‘a stroke of luck’, says Griffa. In 2015, a retrospective organised by Andrea Bellini, director of the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, was staged at that venue in Geneva, with further exhibitions in Bergen, Rome, and Porto succeeding it as part of a collaborative curatorial project; last year, paintings by Griffa featured in the Venice Biennale for the first time since 1980. ‘Giorgio Griffa: A Continuous Becoming’, which includes works from the 1960s to the present day and is Griffa’s first solo exhibition in London, opened at Camden Arts Centre at the end of January (until 8 April).

Born in Turin in 1936, Griffa began to study painting while a boy, sent to classes after his family had noticed his aptitude for copying a postcard. But he went on to take a law degree, and later worked for a time as a lawyer alongside his father and brother in the mornings while he began applying himself to painting once again in the afternoons. If the law taught him anything, he says, citing favourite pastiches of legal jargon by Erasmus and Rabelais, it was that complex expression does not convey nuanced thought: ‘I probably realised that a very simple language – and I also realised this through poetry, whether Pound or Eliot or Ginsberg – can encapsulate an immense complexity. It’s fundamental.’

Griffa’s painting in this period was figurative, and executed in oils. It was not until 1968 that he began to develop the technique that still characterises his paintings to this day. Turin had grown rapidly in the post-war years, with an influx of workers from the south of Italy to join Fiat and other manufacturers, and this time of transformation generated an atmosphere of creative experimentation and possibility (Griffa also recalls how the shops in Turin began to sell fruit and vegetables from across the Italian peninsula, rather than just the Piedmont region). And the most significant artistic challenges came from those artists who, partly as a reaction against the gloss of Pop art and the sleek lines of minimalism, began to create sculptures from crude or simple materials – which led the critic Germano Celant to group them as proponents of what he called Arte Povera.

Griffa became closely associated with many of these artists, not least because he was taken up by Gian Enzo Sperone, whose gallery in Turin was so instrumental for the development and promotion of their work. From them came a feeling for materiality that transformed how Griffa thought about painting. He saw, he explains, how they understood ‘the intelligence of the material’ – in the way, for instance, that Giuseppe Penone embedded a bronze cast of his hand and lower arm in the tree trunk that would slowly envelop it, or that Giovanni Anselmo positioned large stones by reading the compasses that he incorporated into his works. In his own work, Griffa began to make marks ‘that existed for their own sake’.

It was in the context of such experimentations, and through his friendships with Alighiero Boetti, Aldo Mondino, and others, that Griffa’s own original thinking about painting and the role of the painter emerged. ‘Rather than an artist taking an object,’ he says ‘and making it live like the statue of Pygmalion, there had been a shift whereby the artist no longer had the material in the service of their own hand, but put their hand in the service of the intelligence of the material.’ Where painting was concerned, he realised, this meant quelling any desire to make Romantic, gestural brushstrokes, in favour of a technique in which self-expression was suppressed and the artist shared the same creative status as his tools. ‘I realised that it was necessary to cool down the emotional relationship between the painter and the painting,’ he says, ‘and that helped me to realise that painting has its own identity which is not just the projection of the individual. […] I realised that I needed to forget myself.’

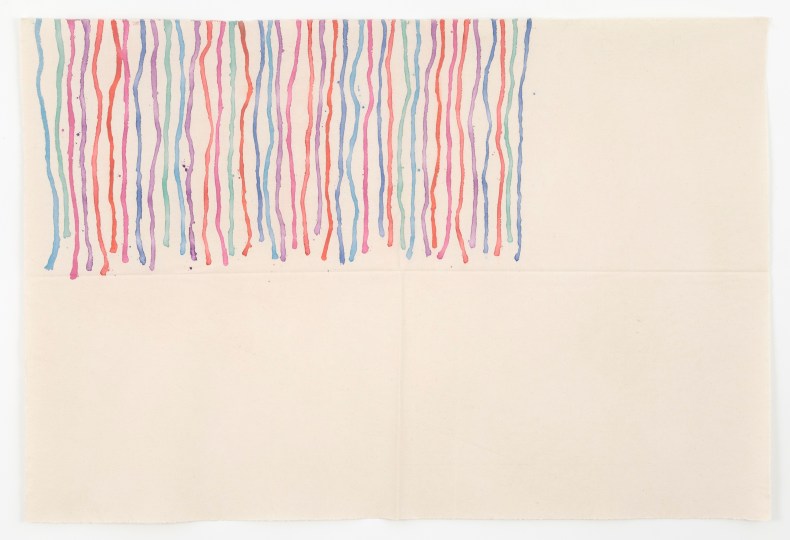

Dall’alto (1968), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Giulio Caresio

It was with an exhibition at Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone in early 1969 that the implications of this became clear. Sperone, along with the journalist and gallerist Luciano Pistoi, was one of the great ‘catalysts’ for the Turin avant-garde, and Griffa is still thankful for what that show made possible. This was the first time that he had painted on unprimed, unstretched canvases. These were laid out like sheets on the floor, and he worked slowly across them, crouching or kneeling on the material in a way that aligned him with his tools. The paintings were then displayed unframed, pinned to the wall with small nails. ‘[Sperone] was the first to accept that I could have a canvas without a stretcher,’ Griffa says. ‘In fact, he liked it.’

Griffa continues to paint on horizontal canvases to this day; when I visit his studio, several large works in progress line the floor of his studio, each spanning several metres like unfurled rolls of fabric. I ask him whether, at the time, he knew Hans Namuth’s photographs of Pollock in full flow on an action painting, all movement and bravado. Although Pollock has influenced his thinking, he says, painting on the floor has for him never approached the conscious drama of the American painter’s method. In fact, it has meant quite the opposite, enabling ‘a slow gesture, controlled, in the sense that I needed and still need today to proceed as the work dictates, but while understanding it’. It encouraged a Zen-like mode of concentration – and Griffa had discovered Zen philosophy as a young man – through which, as he moved physically across the canvas, becoming but one element alongside those of brush, paint and surface, the temporality of painting was ‘no longer the time of the clock, but the internal time of the work’.

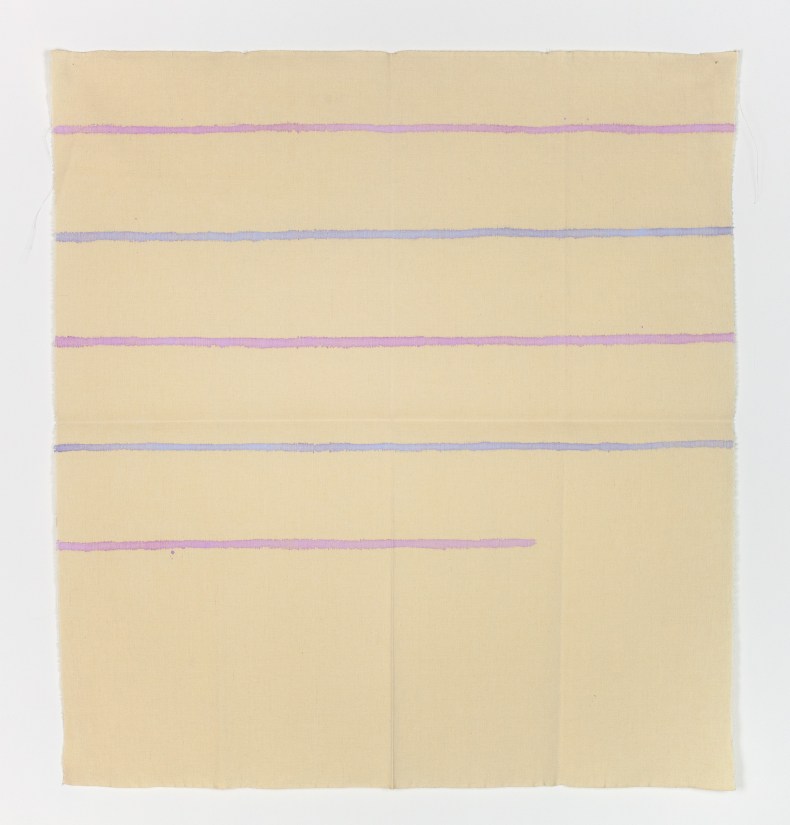

Linee orizzontali (1974), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Giulio Caresio; courtesy Archivio Giorgio Griffa

His new attitude to the material also led him to abandon oil paint. He began to work with water-based acrylic paints, which, mixed thinly, seeped into the unprimed canvas and bled into one another as he applied them in simple repeating marks, or in groups of horizontal, vertical or oblique parallel lines. The rawness of the resulting colour fields, along with the large areas of unpainted canvas, gives many of his paintings a provisional feeling, emphasising his convictions about the independent life of the materials. And like the frescoes that he studied as a teenager, his own watery paintings seem to fluctuate as they are viewed: ‘Oil paint has its own internal light, but water-based paint reflects the light and changes as the light changes.’

Linee oblique (1969), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Giulio Caresio

For all that he was indebted to the leading figures of Arte Povera (he later pays homage to Mario Merz, Anselmo, and others, in the Alter Ego series, which began in the late ’70s and which also refers to artists from Tintoretto to Brice Marden), Griffa’s association with this loose group also isolated him as an artist. Indeed, as Andrea Bellini has written, ‘Griffa was one of the most discreet and isolated in [the] group of young people who revolved around Sperone’s gallery’. As he persisted with painting, his work sat at a remove from the sculptural experiments of his peers – and from the market for them. His sympathy for their thinking, meanwhile, meant that he was detached from other developments in Italian painting; although he has sometimes been grouped with the Pittura Analitica movement of the 1970s, with its critical investigations of what it means to paint, Griffa has just as often declined the label.

Instead, his closest companions have in a sense been those poets and scientists whom he has encountered through reading and rereading. ‘I’ve always travelled through books’, he tells me. ‘I am a nomad, as it were, in my mind and in painting’. For Griffa, poetry has provided an intensity of thought and expression that surpasses the local specificities of their languages (he likes to read editions with facing-page translations, preferably by poets). Among his most significant influences are T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound; in 2002, Griffa published Nelle orme dei Cantos (In the Footsteps of the Cantos), an artist’s book in which his own marks flourish around fragments of Pound’s vast, cryptic poem.

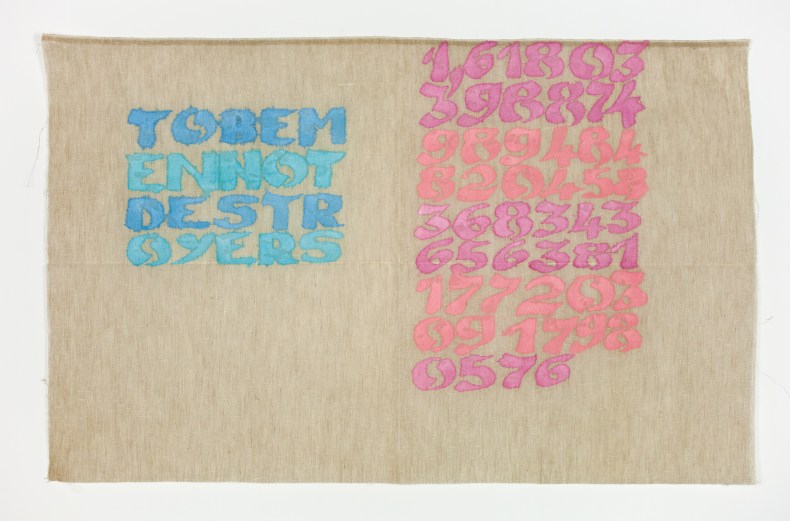

Canone aureo 576 (Pound) (2016), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Giulio Caresio

The work of Allen Ginsberg has also provided a touchstone; Ginsberg’s elegy for his mother, ‘Kaddish’, is for Griffa ‘one of the most beautiful things that has ever been written’. He vividly remembers Ginsberg’s visit to Turin in 1967, when he read at the bookshop, at that time called Hellas, which was owned by the radical activist Angelo Pezzana: ‘He read Howl, in this small bookshop, […] we were all in the basement – today it wouldn’t be possible because of health and safety laws – we were packed in there, and he read with this wonderful voice’. He shows me a City Lights Books edition of Howl, signed by Ginsberg, with petals or fronds scrawled by the poet springing from the ‘O’ on the title page.

It is Griffa’s interest in physics, and in particular particle physics, that has informed much of his thinking in recent decades. ‘In the first half of the last century, there was an incredible transformation in human knowledge,’ he says, ‘largely brought about through the study of physics, which only scientists really understood, but which we are now starting to become more aware of.’ He has read widely in this area, and cites the impact of books by scientists such as Richard Feynman and Fritjof Capra, which brought complex ideas to wider audiences. For him, one effect of such publications has been to reconcile his own earlier intuition about material with those scientific discoveries about the structure of matter that have transformed the framework of human knowledge: ‘From ancient times until recently, the world was divided for us between the inanimate and animate worlds,’ he says. ‘Now we realise that the whole world is living, because what we thought was the solid, stationary part of it has, with the advent of subatomic physics, been revealed as something that is alive.’

Tre colori (1998), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Cathy Carver; courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York

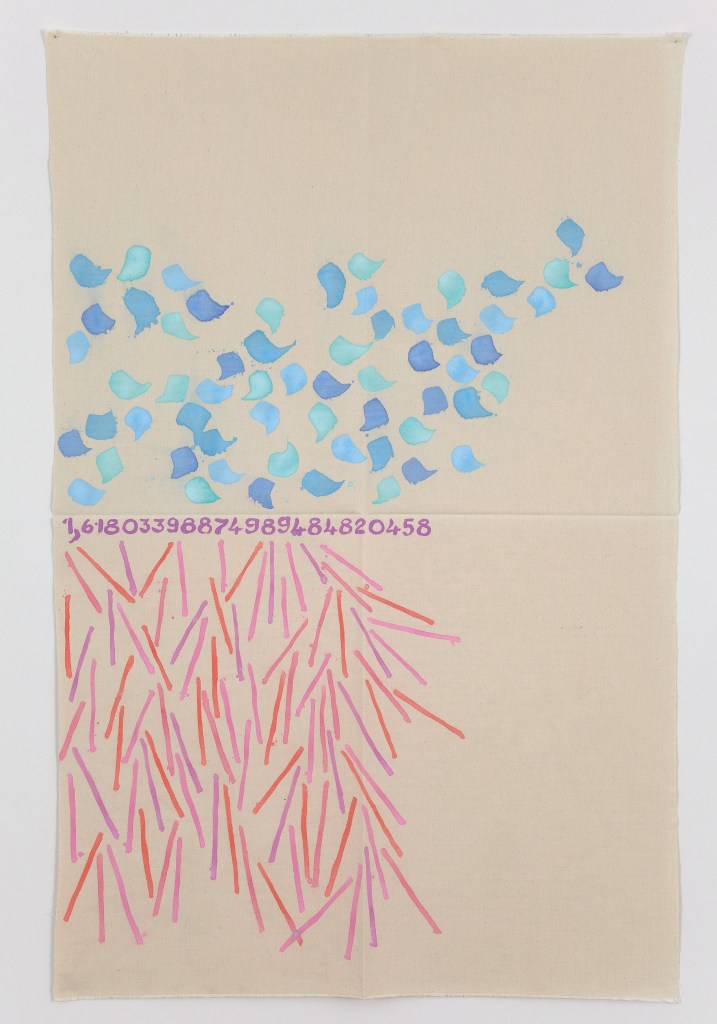

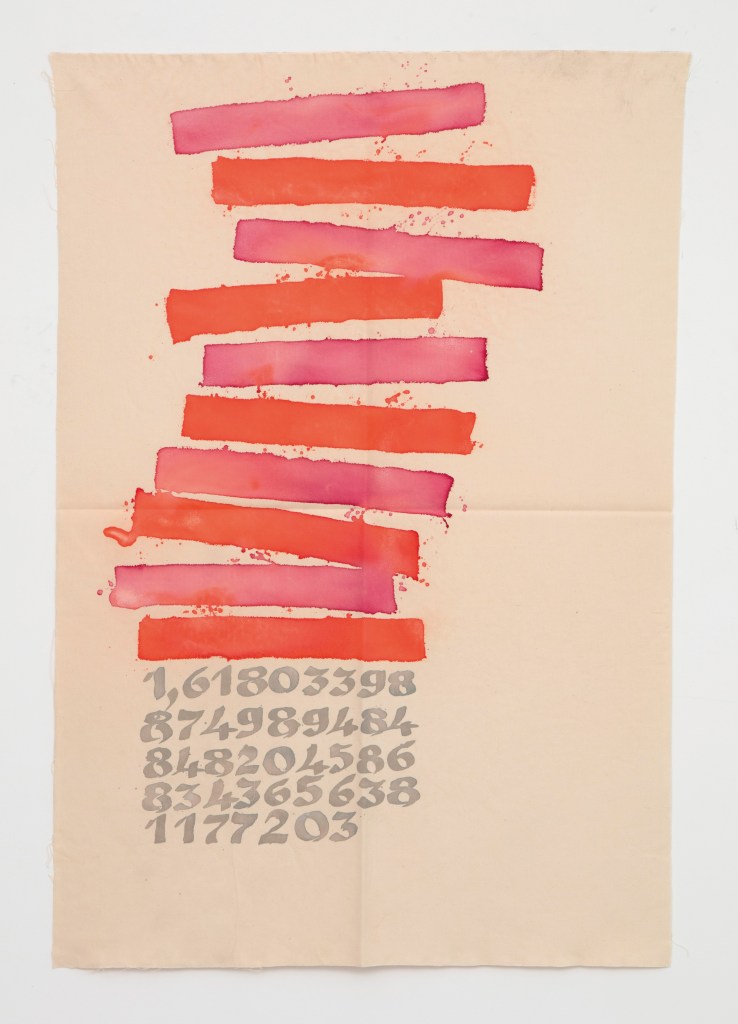

Griffa’s exploration of physics, and the corresponding world of mathematics, has made itself apparent in his mark-making. It is there in the arabesques, wavy lines and diverse symbols that began to appear in his work during the 1980s. ‘The arabesque’, he says, ‘represents at once linear time and circular time, because it goes backwards while moving further forward.’ Most prominently, it has led to a fascination with the Golden Section, the never-ending (or ‘irrational’) number that has so occupied mathematicians from Euclid onwards, and that has engrossed so many artists and architects. For Griffa, the intellectual allure of this number lies in its endless nature and in the way that, however many decimal places are added to it, it always heads further into the unknown.

Canone Aureo 458 (2012), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Jean Vong; courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York

‘Knowledge is always temporary: it has never been definitive,’ he says. ‘Today we know that many things are unknown, and that the unknown is one of the positive aspects of science and no longer on the negative side.’ In Griffa’s paintings, then, the Golden Section has come to stand for the contingency of human knowledge and experience, as well as our new-found acceptance of that state. In his Canone aureo series, which runs to hundreds of works, Griffa has painted the number ‘1.618…’ on to the canvas to varying decimal places – foregrounding the mysteries of knowledge, and the mysteries of painting, and suggesting that his works are not so much unfinished as unfinishable.

Canone Aureo 203 (2016), Giorgio Griffa. Photo: Jean Vong; courtesy Archivio Giorgio Griffa and Casey Kaplan, New York

For all his avant-garde sensibilities, Griffa sees himself as a traditional painter. ‘I do what painters have always done,’ he says, ‘which is give an image to the world that accords with the knowledge and culture of their time.’ Painters, he continues, are like ‘antennae that pick up whatever’s in the air.’ But in his case, as he recognises, many of those signals are richly indecipherable.

‘Giorgio Griffa: A Continuous Becoming’ is at Camden Arts Centre until 8 April.

From the February issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.