An endearing doodle of a gondola is among the contextualising ephemera displayed in a room adjoining this show of paintings by Howard Hodgkin from 1978–99, touted as his ‘classic’ period. Patrick Caulfield drew it in a tiny visitor’s book at Hodgkin’s show for the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1984, when indeed the artist was propelled into what pop-music critics call an imperial phase. How useful is it to suggest a ring fence around a certain period and call it the apex? This circumscription casts the work of preceding years, featuring such gems as Small Durand Gardens (1974), as gestative – and suggests a subsequent decline in quality, when Hodgkin’s later work is, by and large, a blaze of glory. But for those in the business of defining a classic period this show, curated by Paul Moorhouse, gets it right. The ’80s and ’90s find Hodgkin newly fluent in a more pliable, upgraded version of his language, extending the game with demanding subjects and supports, giving rise to the most Hodgkinian Hodgkins.

After Visiting David Hockney (second version) (1991–92), Howard Hodgkin. © Howard Hodgkin Estate

These works are the product of sustained deliberation, accrued layers of painting, where means, medium and memory are in synergy. Hodgkin set himself a taxing task: to paint that ‘almost impossibly nebulous’ subject, his recollections. Fleeting sensations – that Indian sky, clean sheets in Venice – may be acutely vivid but are inevitably foggy, too. The hook in these paintings is the palpable sense that remains of the process of finding a supple resolution for the task of depicting them. They are like involved, wine-fuelled conversations. Hodgkin took as long as it took, which was often many years, working on a single piece. This patient solving of the riddle, through longueurs of reflection and an increasingly resourceful touch, is what untwists the lid a little for the viewer. They are offered a whiff of something pungent, of lived experience.

Several fundamentals intertwine to make this period Hodgkin’s most sui generis work. His repertoire of marks – stripe, the windscreen-wiper arc, the sweep, the wave, the macro-pointillist dot – is distilled. All manner of found frames are adopted as eccentric surface terrain. The oil paint, modified with Liquin, is applied in a range of manners – shifting from vanishingly thin glazes to frosting-like impasto. Sometimes the lamination is frenzied, more often it resolves daintily.

In Tangier (1987–90), Howard Hodgkin. © Howard Hodgkin Estate

The framing of the pictures frequently suggests a glimpse out the window, from the corner of your eye, as a curtain is drawn or condensation wiped away. Or, as in From a Swiss Train (1996–97) – clean licks of pale cobalt blue, white, and green slipping away from a grey border – a view tugged out of sight on entering a tunnel. The prevailing emotional subject was best described by his friend Susan Sontag: ‘the rueful shadow cast on all pleasures when they are framed, theatricalized even, as acts of memory’. His marks are deployed to various effect: to tighten structure, compress glimpses and generate acute moments of feeling, or dance, glide and swim across the surface – witness the fluidity of forms in After Visiting David Hockney (second version) (1991–92).

Chinoiserie (1994–97), Howard Hodgkin. © Howard Hodgkin Estate

The physical frames, subsumed as they are into the painting proper, are home to much incident – snatches of underlayers peek through joins in the wood. Paint sometimes misses, sometimes clogs recesses, as in the rugged steps of Chinoiserie (1994–97). A frame’s design can significantly inform the rhythm of a painting. The distribution of the leopardskin-like dots in View from Venice (1984–85) is clearly guided by the frame’s dimensions; the ‘misaligning’ of the painted umber-into-mustard stripes and the successive inset frames that form the borders of It Can’t Be True (1987–90) creates a dizzying effect, perfectly evoking the light-headed nausea that comes with unpleasant news. In the case of Old Sky (1996–97), the warm sepia of the frame, its chipped moulding, and its abraded varnish all seem to have inspired Hodgkin’s gust of gold and Venetian red. It’s a glowing hearth of a painting.

Those who are cool towards Hodgkin wince at the collision of erudition and breathless gesture. Maybe After Degas (1993) would give them pause to reconsider. There can’t be many suaver Hodgkin paintings, yet beneath its lightly worn complexity primal forces lurk. A wild, russet landscape is stirring but hemmed in by a strange purse-lipped emerald green frame. An almost apprehensible form – perhaps a shoulder blade, perhaps a warm rock face – emerges from the blur. Characteristically, the emerald laps over on to the central panel, skewing its edges, a wonky border that, no doubt, is a precisely felt modulation. Going to America (1999) is brasher – a computer-desktop pastoral scene flanked by long strokes of black over Barbie pink. Like several of Hodgkin’s paintings, its slippery window frame is a close relative of De Kooning’s Door to the River (1960).

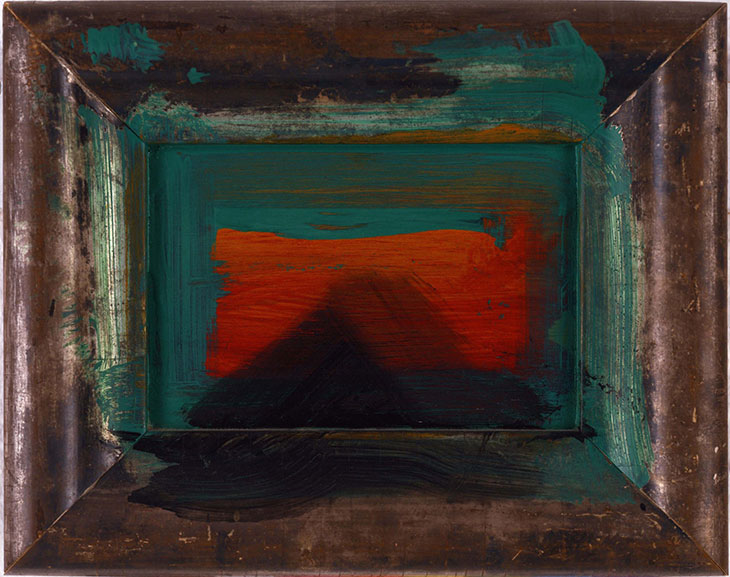

A Pyramid for Antony (1986–88), Howard Hodgkin © Howard Hodgkin Estate

The only large picture included, In Tangier (1987–90), slightly has the wind taken out of its sails by A Pyramid for Antony (1986–88), the tiniest. (The latter work’s title refers to Hodgkin’s long-term partner, the music writer Antony Peattie.) At 19 centimetres high, this smoky, ethereal miniature is a prime example of the ‘evasiveness of reality’ the artist sought. The pyramid itself shrinks from view, casting a translucent shadow – or, perhaps, caught in the act of becoming a dusky afterimage.

‘Howard Hodgkin: Memories’ is at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, London, until 11 December.