Flowers play a significant role in British artist Edmund Clark’s powerful exhibition ‘In Place of Hate’ at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, the result of a three-year residency at Europe’s only therapeutic prison, HMP Grendon in Buckinghamshire. The show opens with a lightbox installation set on the floor, which visitors can enter, and which features pressed flowers picked from the prison grounds set into its top. It has the exact dimensions of a cell, as per its title 1.98m2 (2017). As one stands within the tiny space allocated to each prisoner, the sense of claustrophobia is overwhelming. The work makes clear that these fragile flowers can exist in the prison’s harsh environment, yet the reality of confinement is always oppressively present. On another level the installation, which makes visible each plant’s veins and markings, can be understood as a metaphor for the inmates’ experience at Grendon, where every action and flaw is scrutinised by their peers and held to account in a rigorously democratic system that differs dramatically from conventional prisons.

1.98 m2 (detail) (2017), Edmund Clark. Courtesy the artist, Ikon and Flowers Gallery

Clark has much experience in dealing with issues of visibility, control, and censorship, having previously made series of works focusing on Guantanamo Bay (If the Light Goes Out) and the CIA’s secret detention centres, known as ‘black sites’ (Negative Publicity). For this exhibition, which includes photography, video and installation, Clark overcomes the limitations on photographing prisoners both by rendering their images indistinct and by presenting them in masks. He conveys the materiality of the prison infrastructure by incorporating Grendon’s actual furnishings. In the installation My Shadow’s Reflection (2017), for instance, Clark uses five green prison bedsheets as screens upon which are projected enlarged images – of flowers, of the stark prison architecture, and of the prisoners. These latter images, taken with a pinhole camera over six-minute-long exposures, loom blurrily out of the cloth like monstrous versions of the Turin shroud. Yet these phantasms exude vulnerability, pain and fear, as if the sheets themselves might reveal the anguish of the bodies they have enveloped. The prisoners’ responses to these portraits, displayed separately on a monitor, range from joy at feeling reborn, to anger at their own inhumanity. ‘It’s the best photograph of me ever,’ says one. ‘It’s like you are looking through me but you can see the warmth of my body or my organs or the energy inside me, like a heat recognition camera.’

Installation view, ‘Edmund Clark: In Place of Hate’, Ikon Gallery, 2017. Courtesy the artist, Ikon and Flowers Gallery

An exhibition like this could risk appearing patronising, but Clark’s compassion and respect are evident, both for the staff and for the inmates, many of whom have served decades in the prison system for serious crimes. Despite the inherent restriction of the prison setting, there’s an optimism at Grendon, fostered by its nurturing, therapeutic approach. Clark’s film Oresteia (2017) demonstrates group therapy in action: staff trained in psychodrama act out the roles of Aeschylus’s trilogy and invite the inmates, who wear white masks, to identify with characters driven by age-old emotions such as revenge, rage, or justice. Seated in a circle on the same blue chairs used in prison therapy sessions, the viewer has the feeling of participating in this forceful experience as the prisoners, guided by the staff, articulate remorse, disgust and sadness as they come to understand their own actions. One can only imagine the psychological turmoil they have undergone to reach this point.

Installation view, ‘Edmund Clark: In Place of Hate’, Ikon Gallery, 2017. Courtesy the artist, Ikon and Flowers Gallery

Clark’s show is aptly paired with the first UK exhibition devoted to the paintings, drawings and photographs of convict artist Thomas Bock (c. 1793–1855), who was sentenced to transportation to Tasmania in 1823 for attempting to induce a miscarriage in his mistress. There Bock’s artistic skills were soon put to use making portraits of British colonial worthies and of captured bushrangers before and after execution. These works are remarkable for their honesty, resisting the temptation to pass moral judgement through caricature or emphasis of physical defects.

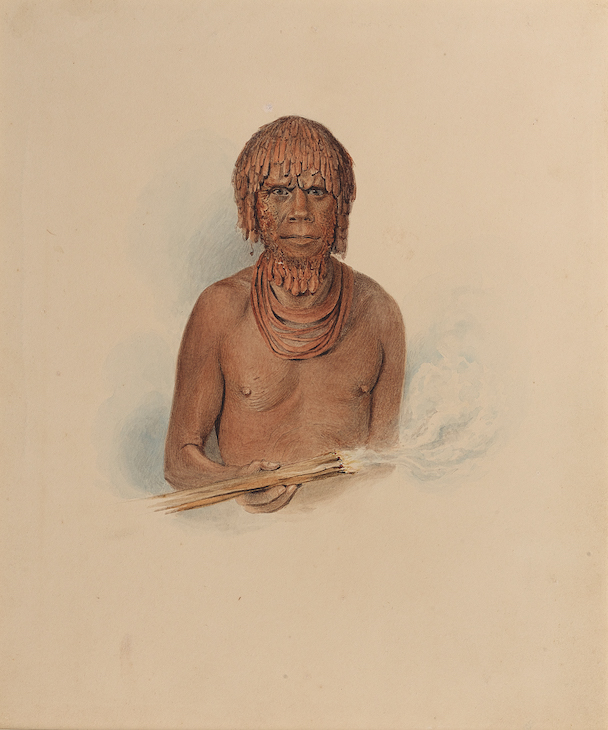

Bock’s most important legacy remains his portraits of Tasmanian Aboriginal people, commissioned by the government-appointed conciliator, George Augustus Robinson. These delicate, haunting watercolours are notable for the dignity they bestow upon the sitters, who faced brutal persecution from colonists. They include expressive paintings of indigenous leaders who resisted capture and of Trukanini, a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman. Prominently exhibited in the centre of the room is Bock’s portrait from 1842 of the orphaned Aboriginal child Mithina, who was adopted for a time by the Lieutenant-Governor’s wife, Jane Franklin. In a fashionable red Western dress, Mithina gazes calmly out of the canvas with wide, gentle eyes, not to know that at just 17 she would die, abandoned and an alcoholic.

Manalargenna (1831–35), Thomas Bock. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Although very different artists, Bock and Clark share a sensitive approach to their subjects by underscoring their humanity. Both of these exhibitions argue for an understanding of those who exist beyond mainstream society’s frame of vision. As a result, the viewer is invited to reconsider their attitude toward incarceration and to empathise with people whose fate was often determined at birth.

Thomas Bock and Edmund Clark is at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until 11 March.

From the February issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here