A round-up of the best works of art to have recently entered public collections

Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire

Moses (c. 1618–19), Guercino

In 2022 a painting of Moses, attributed to an unknown follower of Guido Reni, was put up for auction in Paris at an estimate of €5,000–€6,000. Several dealers believed it to be a rare work by Guercino from 1618–19, largely on account of its similarity with a known work by the Bolognese painter, Head of an Old Man (c. 1619–20). It was bought for €800,000 by Fabrizio Moretti, who had its authenticity confirmed by experts before exhibiting it at his new Paris gallery last year. Now the Rothschild Foundation, which manages Waddesdon Manor on behalf of the National Trust, has purchased the painting. It depicts the Old Testament figure in a striking pose: his head and hands raised towards the heavens, simultaneously in communion with God and in a state of seeming recoil. The canvas will go on display in the exhibition ‘Guercino at Waddesdon: King David and the Wise Women’ (20 March–27 October), alongside four later works by the Old Master, including the imposing King David (1651), which fetched £5.2 million at auction in 2010 – the record price for a Guercino. After the exhibition, Moses is expected to join King David in Waddesdon’s sizeable permanent collection.

Moses (1568), Guercino. Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire. Photo: Moretti Gallery

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Lady Gertrude Savile, Marchioness of Halifax (c. 1679), Mary Beale

Mary Beale (1633–99), often cited as the first professional woman painter in Britain, had a formidable reputation in her day. She slowly faded from view in the centuries after her death and has suffered countless posthumous misattributions. Her portrait of Lady Gertrude Savile, Marchioness of Halifax, is one of those formerly misattributed works: in 2021 the painting came up for auction, catalogued as being by one of Henri Gascar’s circle, and sold for just over £3,000. The buyer, Peter Harrison, found a Christie’s document from 1918 affixed to the back of the painting, naming Peter Lely as its creator. Now, after extensive research confirming the portrait as Beale’s, Harrison has sold it to the MFA in Boston for a six-figure sum. Interest in Beale’s work has been on the rise in the UK in recent years; the MFA becoming one of the first US galleries to own a Beale is a sign that enthusiasm is spreading across the pond too.

Lady Gertrude Savile, Marchioness of Halifax (c. 1679), Mary Beale. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

National Gallery of Art, Washington

27 artworks by Joseph Cornell

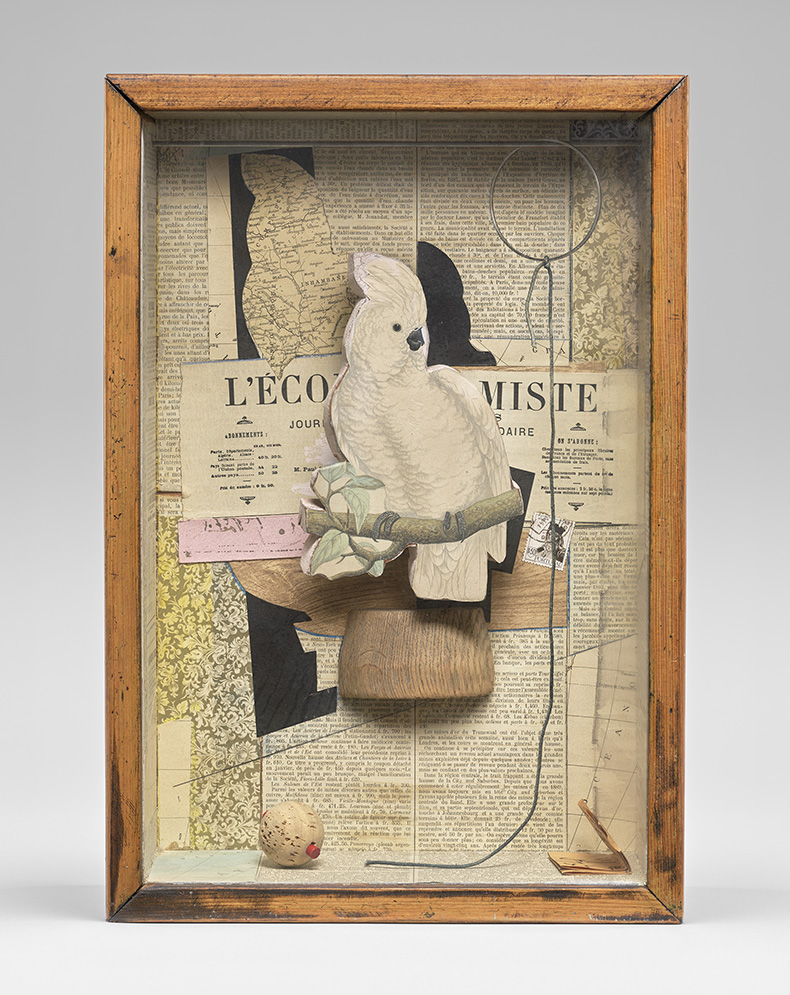

Twenty boxes and 7 collages by Joseph Cornell have been gifted to the National Gallery in Washington, more than doubling their collection of works by the avant-garde artist and filmmaker. Cornell was a fascinating figure: a recluse who for much of his life lived with his mother and rarely left New York, he was also friends with some of the giants of 20th-century art, from Warhol and de Kooning to Rothko and Duchamp. Cornell has never attained the same renown as those figures, but he was a strikingly original artist, known for his surrealist assemblages of paper and objects housed in wooden boxes. Some of those acquired by the gallery show evidence of Cornell’s influences, such as Variétés Apollinaris (1953), a box that includes a reproduction of the young ballet dancer in Picasso’s dream-like painting Family of Saltimbanques (1905). A Parrot for Juan Gris (1953–54), which references the Spanish painter’s 1915 work Fantômas (also held by the National Gallery of Art), is perhaps the most exquisite example of the Aviaries series that Cornell embarked on in 1943.

A Parrot for Juan Gris (1953–54), Joseph Cornell. National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The Hope Cup (1855), Jean-Valentin Morel

The Louvre’s collection of objets d’art stops in 1848, at the end of the reign of King Louis-Philippe, so when the Musée d’Orsay opened in 1986, part of its intention was to provide a home for all those artefacts, created from the mid 19th century onwards, that the Louvre had no place for. The Orsay’s considerable collection now has a new recruit in the form of the Hope Cup, an intricate jasper, gold and enamel piece created by the skilled French jeweller Jean-Valentin Morel, with help from various craftsmen and sculptors. It was presented at the 1855 Paris Exposition, where it earned its creator a medal of honour. At the top Perseus is depicted slaying the dragon to liberate Andromeda, who stands in chains towards the bottom, flanked by six Nereids, all while a Medusa stares down fiercely from the other side of the cup. The Hope Cup joins another ornate 19th-century object that references Greek myth, Gustave Doré’s sculpture Fate and Love (1877), which was acquired by the Orsay in December.

The Hope Cup (1855), Jean-Valentin Morel. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Louvre Museum, Paris

Viscount Marcellus’s Venus de Milo (second half of 19th century), from the Louvre workshop

The Louvre has acquired a plaster cast of its most famous sculpture, the Venus de Milo (c. 130–100 BC), from the descendants of Lodoïs de Marcellus, the viscount who brought the original statue to France in 1821 after it was discovered in Greece. This copy was commissioned by King Louis-Philippe two decades later and presented to Marcellus. The sale also includes the contents of the library at the Chateau Marcellus near Bordeaux.

Viscount Marcellus’s Venus de Milo (second half of 19th century), from the Louvre workshop. Photo: © Artcurial