Zaha Hadid, who has died aged 65, was the most successful female architect of her generation. Regardless of gender, she was one of the most important British architects of the past 100 years. She had won every significant international honour architecture can offer – including the Pritzker, the RIBA’s Royal Gold Medal, the Praemium Imperiale – and is the only person to have won the RIBA Stirling Prize for best British building in consecutive years. Her death leaves British architecture immeasurably poorer.

The Hadid style brought together clashing volumes, razor-sharp prows, gravity-mocking cantilevers, and swooping, unstoppable lines. It makes for a brash, uncompromising body of work that was often highly controversial. Hadid’s first significant built work was a fire station on the campus of the furniture manufacturer Vitra in Weil am Rhein, southern Germany, memorable for a roof that jutted into a scalpel-point. But her prodigious talent, revealed through her teaching at the Architectural Association and startling conceptual work, had already made her something of a cult figure within British architecture. In the late 1970s, she had worked at the AA with Rem Koolhaas, Elia Zenghelis and Bernard Tschumi, a fascinating nucleus of 21st-century ideas; before setting up Practice in the UK in 1980, she worked at Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

She rose to general prominence in the UK as the author of the winning entry in a shamefully bungled competition to design an opera house for Cardiff Bay in 1995. This reversal gravely embarrassed British architecture and came to symbolise the deadening philistinism of British officialdom at the time. It undeniably stung for Hadid. But it may have been the making of her reputation.

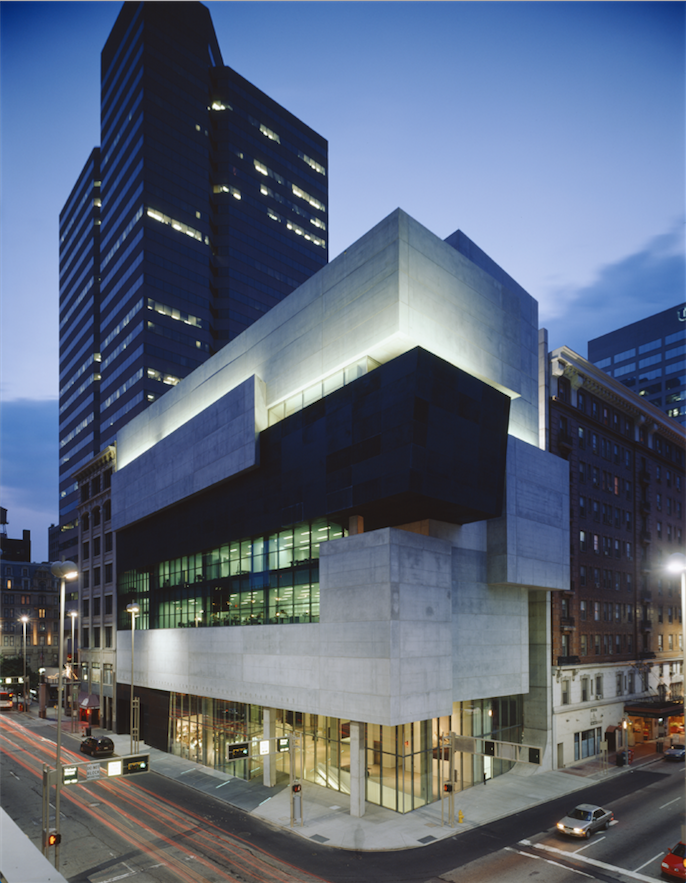

Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, designed by Zaha Hadid in 2003. Photo: © Roland Halbe

A trickle of international commissions followed: a sharp-angled tram terminal in Strasbourg, a ski jump in Innsbruck, and more notably the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, completed in 2003. This extraordinary building, a cuboid crunch of blocks around and enigmatic black slab on a corner site, was Hadid’s first triumph. While being identifiably rooted in avant-garde tradition – notably inter-war constructivism and sculptural brutalism of the 1950s and ’60s – Cincinnati was also undeniably new and distinctively Zaha. From that point on her practice was irresistible.

The world had changed in Hadid’s favour: in the wake of Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim, cities, nations, and corporate clients had woken up to the power of signature architecture to attract attention, visitors and investment. A succession of remarkable large projects followed. The Phaeno Science Centre in Wolfsburg, Germany, is a concrete leviathan with italic perforations, both monumentally solid and apparently ready to spring into motion. Her hub for the BMW plant in Leipzig is a futurist zigzag of glass and steel. The MAXXI Museum in Rome, which divided critical opinion, nevertheless has the power to stun the first-time visitor into silence.

The London Aquatics Centre, designed by Zaha Hadid for the 2012 Olympic Games. Photo: Clive Rose/Getty Images

The UK was still slow to catch on – as late as 2008 she was wondering to Jonathan Meades whether she would ever win a large project here. But the Olympics were already on site, and when the mutations in the Lea Valley at last cease, we are sure to regard her inspiring Aquatics Centre as the jewel in the architectural legacy of 2012. On a smaller scale there has been a run of Zaha projects in this country in recent years – the Evelyn Grace school in south London (which won the Stirling), the swooping Serpentine Sackler Gallery in Hyde Park, a transport museum in Glasgow and a Maggie’s Centre in Kirkcaldy, Scotland.

As her reputation grew to pre-eminence, a certain bombast entered her work, most notably visible in the controversial Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku, Azerbaijan. This, a landmark project for an autocratic ‘Father of the Nation’, is indeed somewhat overbearing – but once the thundering first impression passes, the interest and excitement of its circulation spaces, and the intimacy and warmth of its concert hall, are the features that linger in the mind. Hadid will be remembered for building forms that flowed and folded like silk over sports-car lines – a style much-imitated, but rarely successfully. She was a material and technological innovator like no other, pushing building services and structures to their absolute limit to achieve sometimes surprisingly subtle effects. She had a capacity to confuse opinion special to true mavericks and originals – even her fiercest critics could be moved to praise, and her most passionate admirers often had to admit qualms. She was possessed of a true genius for atria and circulation spaces, giving them unparalleled drama and verve – a gift in an era filled with atria and circulation. In those moments, it’s tempting to think of her as 21st-century architecture’s Beethoven, with work filled with struggle and intensity, but also deep and rich.

It was often said, early in Hadid’s career, that she was simply before her time. She has certainly passed from our company far before her time, with little sign of any slowing in output. But she was, perhaps, more important than someone merely waiting for the right moment to come along – instead, the world had to adapt to her. Future generations will regard us as being very fortunate to have lived in Zaha’s time.