Art Basel Hong Kong takes place in the giant turtle-shaped conference centre which hosted the 1997 handover of the city to China. It is an apt setting for a fair defined by East-West crossovers, in which Asian contemporary art mingles – and often seems to merge – with that of the west. This year’s event, the fourth held by Art Basel, hosted 239 galleries, half of them from the Asia-Pacific region. The international profile of the participating galleries was mirrored in the clientele: roughly half of the major collectors were Chinese or Asian.

Yang Maoyuan’s version of Michelangelo’s David on Platform China’s stand. Photo courtesy the author

At the stand of Beijing gallery Platform China, a stumbling distance from the entrance to the fair, was a work which embodied this mood of cultural crossover – an enlargement of the head of Michelangelo’s David, set on a pallet on the floor, by the Beijing-based Yang Maoyuan. The hero’s nose and Florentine locks have been smoothed off (lost in translation), so as to resemble a piece of garbled 3D printing. Maoyuan’s David has the defiant frown of his Renaissance prototype, but is also neutered – a classical monument displaced and abstracted.

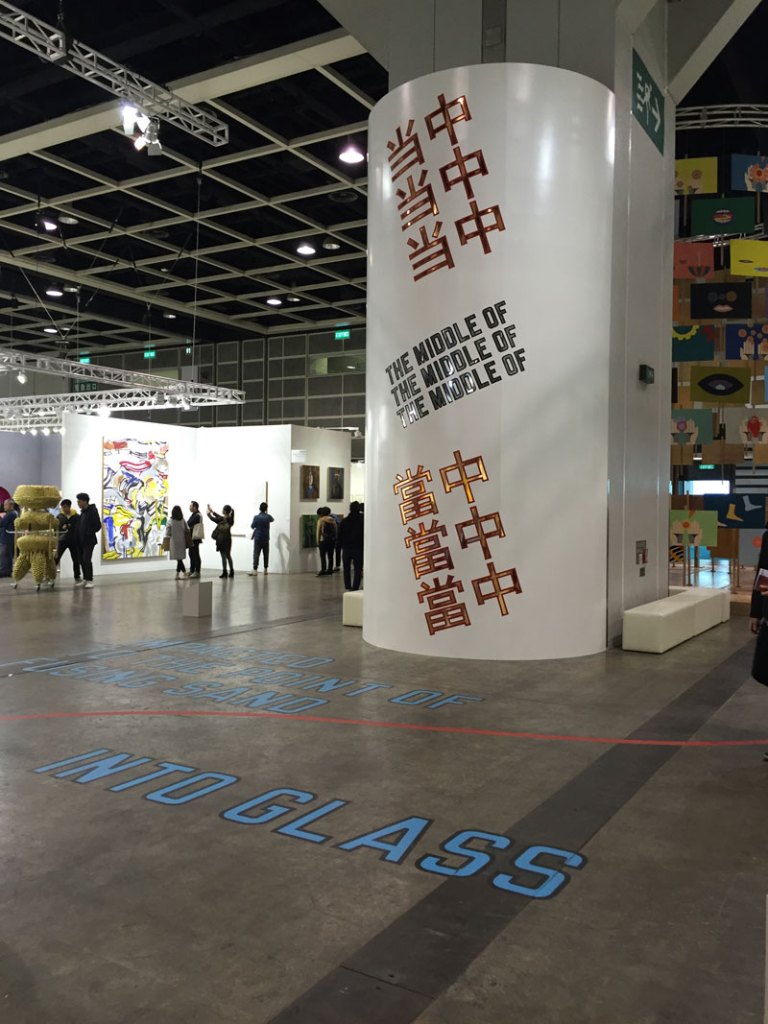

THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF (2012), Lawrence Weiner. Photo courtesy the author

The fair’s two vast floors were studded with attention-grabbing installations by single artists, billed ‘Encounters’. One of the less theatrical, and most compelling, was Lawrence Weiner’s THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF (2012), in which the titular text spread across one of the building’s mammoth pillars, in both English and Chinese, like an advert for something not quite graspable. Art adapted itself to context (a previous iteration of the work, at Documenta 13 in 2012, provided a German translation). It also spilled into its context – Weiner’s disjointed poetry continued on the floor with the words ‘IMPACTED TO THE POINT OF FUSING SAND INTO GLASS’.

The atmosphere elsewhere was one of breezy decompression. New York gallery Greene Naftali had dedicated their stand to an installation by Paul Chan, in which black nylon inflatable ‘gloves’ billow into the shapes of three dancing puffer jackets, animated by blowing machines.

Paul Chan at Greene Naftali was one of the highlights of Art Basel Hong Kong. Photo courtesy the author

Over at David Zwirner’s booth was an exhibition of stellar contemporary painters including Neo Rauch, Marlene Dumas and Michaël Borremans. If the painting-only display was calculated to appeal to the notionally more conservative clientele in Hong Kong, it had paid off – all of the works were sold before the end of the week (including a Luc Tuymans for $1.6 million).

In general, sales seemed to be progressing gradually, although London dealer Anthony Wilkinson was in upbeat mood, conceding that Art Basel Hong Kong is ‘slower than other fairs, but that may be down to the Easter holiday’. A large sombre canvas by George Shaw, Landscape with Fuck All (2015) had garnered lots of interest but no buyers: ‘I think people here prefer brighter colours in general’, he reflected.

Old Master (Angry Samuro) (2016), Nyoman Masriadi, on Paul Kasmin Gallery’s stand. Photo courtesy the author

Many international galleries were shining a spotlight on an Asian-born artist, or Asian-themed work – an obvious nod to the eastern context that was sometimes too obvious. Nyoman Masriadi’s Old Master (Angry Samuro) (2016) at Paul Kasmin Gallery, showed a raging samurai with tree-trunk limbs; while Gladstone Gallery offered the more sedate spectacle of Huang Yong Ping’s Puits neuf (2008), a pair of large ceramic urns. At Galerie Lelong, Spanish artist Jaume Plensa’s marble sculptures Mar Asia, Laura Asia and Paula Europe – giant portrait busts of three women – were proving a popular selfie-stop. The nearby text explained that ‘Their diversity reflects a fluidity between borders and identities.’

Jaume Plensa’s marble sculptures Mar Asia, Laura Asia and Paula Europe proved a popular selfie-stop. Photo courtesy the author

This work and its statement inadvertently summed up much about the fair itself. Art Basel Hong Kong is a microclimate in which cultural differences are accented and blurred by turns, sometimes simultaneously. A work by Wang Yan Cheng at Acquavella might have been mistaken for a Richter squeegee painting. (Chinese art’s absorption of western influence is, incidentally, the subject of an exhibition of paintings by Yan Pei-Ming at Massimo De Carlo’s new Hong Kong space: the artist presents poignant portraits after photographs, each a snapshot of an artist – Freud, Warhol and others – as a young man). At Dominique Lévy, meanwhile, were some examples of Korean Tansaekhwa painting – a salient reminder that modernist abstraction has its own eastern heritage.

Yan Pei-Ming’s portrait of Lucian Freud as a boy, on view at Massimo De Carlo, Hong Kong. Photo courtesy the author

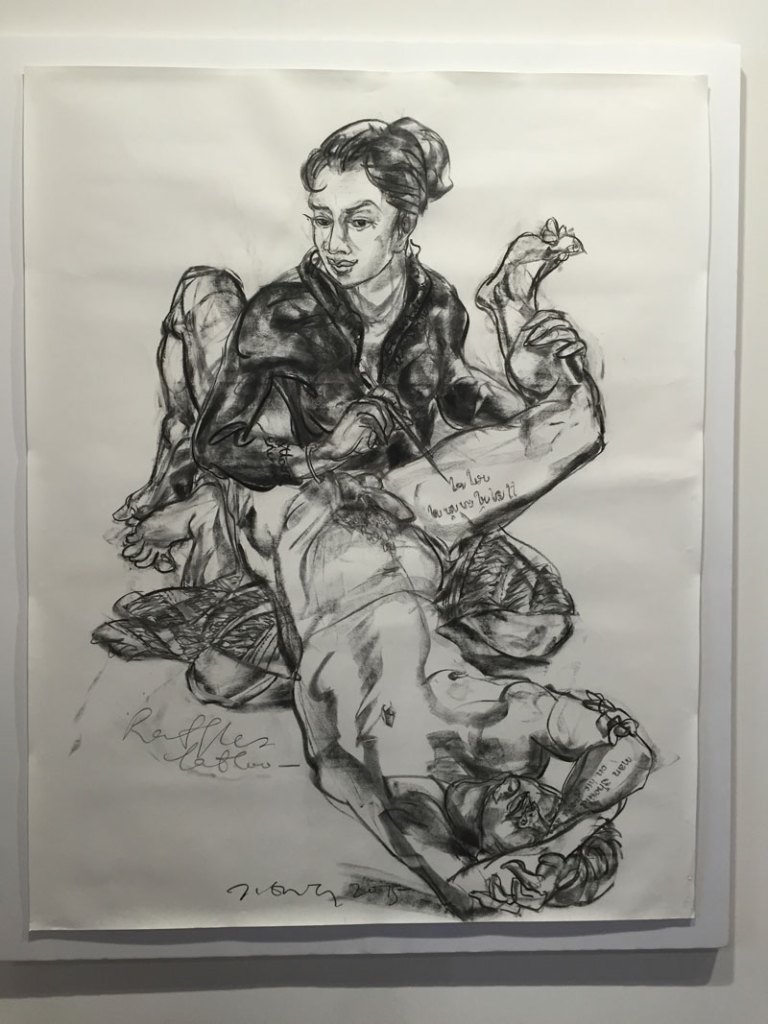

A section titled ‘Insights’ brought together a clutch of different galleries from the Asia-Pacific region, yet their exhibits felt little different – with one or two exceptions – from the rest of the fair, making this special grouping feel unnecessary. One stand-out display here was group of bizarre charcoal drawings titled Java Stories by Jimmy Ong at Singapore’s Fost Gallery. Among the faux-naïve (or perhaps just naïve) scrawled fairy tales and fantasies was Raffles Tattoo, showing a smiling Singaporean lady pricking some words onto a nude man’s thigh.

Raffles Tattoo (2015), Jimmy Ong, on Fost Gallery’s stand. Photo courtesy the author

Like the city in which it takes place, Art Basel Hong Kong is a melting pot, one in which cultural differences often seem to melt away in giddy melee: art can seem to blend into the lingua franca it is often hailed to be. But at certain moments this year, it fractured into something closer to Babel.

Among the exhibitions opening the same week at Hong Kong’s expanding number of international galleries is Tracey Emin’s ‘I Cried Because I Love You’, at White Cube and Lehmann Maupin galleries (until 21 May). Emin’s work is most powerful when it homes in on a single theme, and a condensed range of media, as was the case here. Bodies tangling together in moments of clumsy coitus were the subject, repeated and developed in the form of sketchbook drawings, bleary paintings, and a couple of embroidered canvases artfully copied from drawings. But Emin’s work is most arresting when it is most artless, raw and uncalculating. This sets her apart from the calculating wit and restraint of many younger peers. She has a gritty kind of gravitas that is rare.

Tracey Emin’s ‘I Cried Because I Love You’ at White Cube, Hong Kong. Photo courtesy the author

Art Basel Hong Kong was at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre from 22–26 March.

‘Yan Pei-Ming: It takes a lifetime to become young’, is at Massimo De Carlo, Hong Kong, until 22 May.

‘Tracey Emin: I Cried Because I Love You’ is at White Cube and Lehmann Maupin galleries, Hong Kong, until 21 May.