Picasso once said, ‘If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a Minotaur.’ It is a beautiful image, and, as Picasso’s friend and biographer Sir John Richardson is well aware, the perfect epigraph for this stunning show documenting one of Picasso’s most persistent and revealing obsessions. As the familiar and seldom-seen works Richardson has managed to gather together at the Gagosian reveal, it is not just that Picasso kept returning to images of bulls, bullfighters, and bull-men, it is that the Minotaur, with all its monstrous hybridity, reveals something central about Picasso himself, about his entire oeuvre. It is a figure that speaks to almost everything he did, both in and out of the studio.

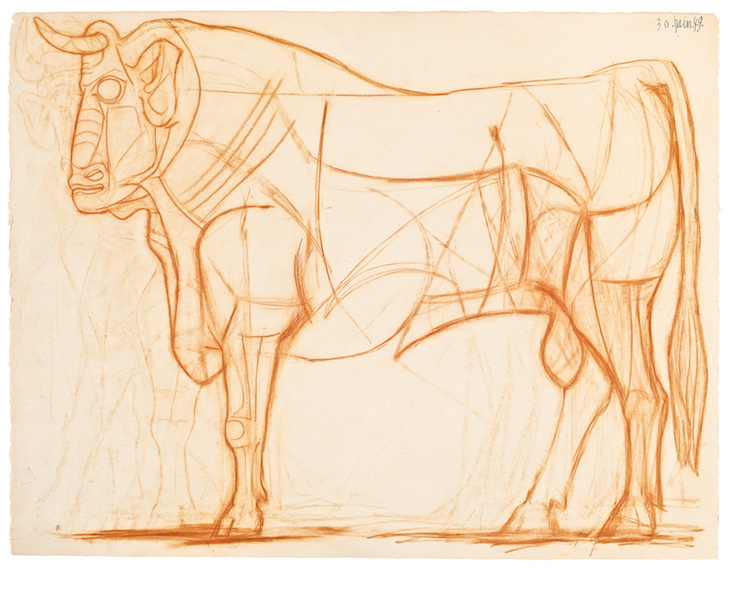

Le taureau (1949), Pablo Picasso. Photo: Marc Domage; Courtesy Gagosian; 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Many of the works here document bulls and bullfighting as a simple testament to Picasso’s Spanishness. The earliest work on display, Le petit picador (1889), dates to when Picasso was just seven years old, already attending bullfights. It is not just a familiar background, though. The bull cult of the Spanish corrida, and the semi-feminised machismo of the matador, feed directly into Picasso’s adult artistic persona. Both are what the anthropologist Clifford Geertz, writing about Balinese cockfights, called ‘deep play’: a game where the stakes are at once unreasonably high and unreasonably low, and which, in the end, keep coming back to projecting and securing certain kinds of male power.

Behind that, too, lies Picasso’s self-alliance to Goya: Goya who once signed himself Francisco de los Toros, who painted himself stood at his easel in a matador’s costume, and who, just as Picasso would with Guernica, took a break from depicting the disasters of war to attend and sketch bullfights. The Goya influence is on full display in 1925’s tender portrait of his son dressed as a bullfighter, Portrait de Paul en torero, holding the same typical red cape seen draped over Picasso’s own shoulder in a photograph from 1955.

Portrait de Paul en torero (1925), Pablo Picasso. Private collection. Photo: Robert McKeever; Courtesy Gagosian; © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

On the other hand, though, the bull and the torero are far from simply Spanish. Drawn by two Spanish transplants to France, Goya and Picasso’s bulls were as French as they were Spanish, charging to their deaths in Bordeaux and the Roman arenas of Arles and Nîmes. Nor are they just French and Spanish; the bull cult represents a cultural skein running all round the Mediterranean, and all the way back through its most ancient history. Picasso, having illustrated the Metamorphoses for Albert Skira’s 1931 edition of the poem, knew that bulls play a recurring role in the ancient myths, and in all the centuries of art drawing on them.

All of which was given apparent historical foundation by Sir Arthur Evans’ 1900 discovery of the remains of Knossos on Crete, supposed home of the Minotaur itself – exhaustively documented in a multivolume series published from 1926–1931, just as Picasso began to fix the monster’s place in his own personal mythology. As Picasso knew very well, to watch a tauromaquia – a Greek term itself – in a Roman amphitheatre in Southern France was to pick up one end of a thread that runs back and forth through history: from Picasso himself to Goya, to Ovid and Ancient Rome, to Velázquez and Titian, and back through Ancient Greece, and back further again to Crete, until it comes to the Minotaur, half-man and half-bull, lurking at the centre of his labyrinth.

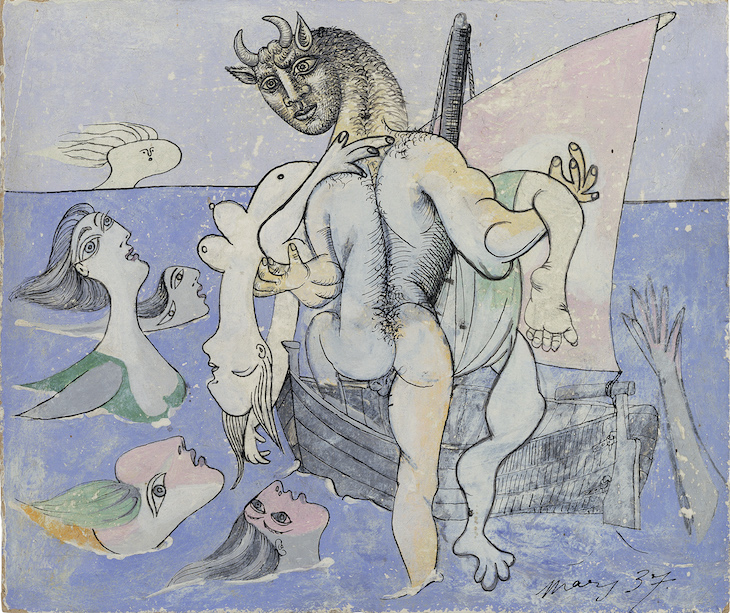

Minotaure et femme (1937), Pablo Picasso. Photo: courtesy the collector; Courtesy Gagosian; © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Monstrosity and monstering are important in this show. Monstrosity is itself a kind of play: a space in which things combine and recombine, altering each other in one body that is both in concert and in competition with itself. Monstering, especially the kind of self-monstering that Picasso engaged in, is another form of deep play – a kind of equivocality in which one gets to say and be two things at once. And the Minotaur is the perfect equivocal kind of monster, the ideal vehicle for Picasso’s self -mythologising. From the 1930s onward, it became an important alter ego for Picasso, who knew full well that he could be a monster, above all to women.

In the myths (recorded in varying versions by Ovid, Plutarch and a host of minor historians and mythographers) the Minotaur is the product of the adultery between Minos’ wife Pasiphae and a bull, condemned to live out his life in the prison of the Labyrinth built by Daedalus. Fed on the youths of Athens, exacted in tribute by their conqueror Minos, he is eventually killed by Theseus, the son of the Athenian king, who with the aid of Minos’ own daughter, Ariadne, enters the Labyrinth, kills him, and finds his way out along a line of thread.

In none of the myths does the Minotaur himself actually play much of a role. There is no particular sense that his cannibalism is desired – that is a punishment inflicted on the Athenians by Minos. And nor is he the real problem for the heroic Theseus – the real enemy there is the Labyrinth itself, inescapable without Ariadne’s string to guide him out. Despite a divine bloodline running back to the sun god Helios, the Minotaur is, in the end, as much a prisoner and a victim as the Athenians he is used to punishing. As Picasso put it to Françoise Gilot in the 1950s, the Minotaur knows he is a monster – something which, by itself, makes him a kind of victim.

Picasso wearing a bull’s head intended for bullfighters’ training, La Californie, Cannes (1959). Photo: Gjon Mili/Time and Life Pictures/Getty Image; Courtesy Gagosian; © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

If it is hard to see Picasso as a victim, especially vis-à-vis the women of his life, he no doubt saw himself that way, beneath the bull’s head of his own monstrosity. The protracted marital crisis caused from 1927 onward by his love for Marie-Thérèse Walter, and his wife Olga’s refusal to grant a divorce, plays out through the Minotaur across several of the works on display here, especially in the Suite Vollard etchings (1930–36, published 1937), and the astonishing Minotauromachie (1935), on display in each of its successive states. Picasso – not averse to literally donning a bull’s head and playing the Minotaur – knew that monstering himself was both a boast and a confession.

La Minotauromachie VII (1935), Pablo Picasso. Photo: Prudence Cumming Associates; Courtesy Gagosian; 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

His Minotaurs appear in scenes both of rape and of tender eroticism, as monsters and as victims and as heroes. In one piece from 1937, Minotaure dans une barque sauvant une femme, the monster is a saviour, hoisting a limp woman into his boat. In the Minotauromachie, the Minotaur, hulkingly huge on the right of the etching, reaches his arm out to block the light from a little girl’s candle. The girl is entirely unafraid; the monster, apparently, scared to be seen. But then he is also, as the viewer can hardly fail to notice, beautiful – a self-portrait that, once again, reads as a confession masking a boast, and vice versa.

There is, of course, too much in all this to do much more than scrape the surface. This is a compact show – two rooms, a carefully chosen selection of works, viewable in a brief visit – but it has astonishing depth. I have not seen such a brilliantly put together show in a long time; even aside from the quality of the works on display, it is a curatorial triumph for Sir John Richardson and Gagosian. See it while you can.

‘Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors’ is at the Gagosian, London until 25 August.