Wampum belts – rectangular bands woven of white and purple shell beads – have been central to the maintenance of peaceful relationships among the Indigenous and settler nations of North America since contact began in the early 17th century. They have also consistently been misunderstood and appropriated into European regimes of value and hierarchies of culture – identified as a form of money and collected and displayed as curiosities, as examples of primitive technologies, and as ‘art’. Today acknowledged as key items of cultural patrimony, they have also been the focus of successful restitution claims. How did these misrepresentations and mistranslations arise? And how did wampum belts emerge as quintessential tools for the negotiation of new kinds of relationships among Indigenous nations and newcomers in the ‘contact zones’ of North America in the 17th and 18th centuries?

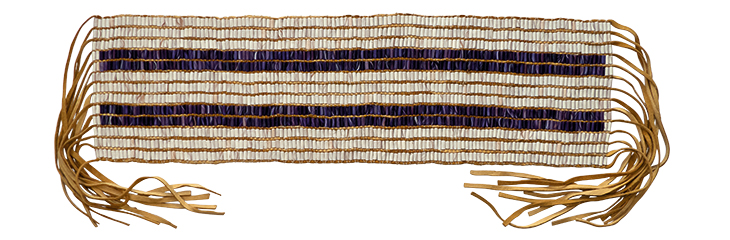

A 19th-century dictionary that defined kahionni, the term used for these belts by the Kanienkehaka (Mohawk), as ‘a river formed by the hand of man’ is suggestive of the eloquent poetics and intellectual power that found expression in the materiality of the belts and their interwoven images. Rivers divide territories and their human communities from each other, but also offer channels for interconnection and mutual support. Wampums were intended to realise these potentials through their combination of spiritual resonance and mnemonic function. The Two Row wampum – the belt that is most often invoked by Indigenous leaders today – expresses these ideals with compelling graphic simplicity. Two rows of purple beads representing the paths of an Indigenous canoe and a European ship, travelling down the same river, run across the centre of a field of white beads. Parallel, never intersecting, the image embodies the concept of kaswentha, or peaceful coexistence and non-interference in the affairs of sovereign nations. Documents suggest that this ideal relationship was first given material form – possibly that of the Two Row – in around 1613 to record an agreement reached by Kanienkehaka representatives with a Dutch trader named Jacob Eelckens in what is now New York State. The belt has been replicated and presented numerous times to remind colonisers and settlers of agreements and treaties made in the spirit of kaswentha but regularly betrayed and forgotten. One of its most recent renewals occurred in 2013, to mark the 400th anniversary of the Two Row, when a flotilla of canoes carried a new iteration of the belt down the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers to present it at the United Nations headquarters in New York City.

Replica of the Two Way wampum belt, made by Darren Bonaparte of Akwesasne in 2000. Photo: © Darren Bonaparte

The value of white shell for ornaments and communal rituals long predates the era of contact. The oral traditions of the Kanienkehaka and other nations that make up the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) confederacy recount that the Creator first revealed beads of white shell to the great culture hero Ayenwatha (Hiawatha) on the dry bed of a lake. As instructed, he used them to make peace and condole mourners after a long and destructive period of internecine warfare. Indigenous peoples throughout the north-east and mid-Atlantic regions have similar traditions of the spiritual origin and compelling power of white shell and other reflective materials characterised by the anthropologist George Hammel as ‘light, bright, and white’ – crystal, mica, and – after European contact – glass beads and silver. Jacques Cartier, one of the earliest explorers, reported, for example, that for the peoples he encountered along the St Lawrence River in the 1530s small white shells, used individually or strung together, were ‘the most precious article they possess’. The annual reports circulated in Europe by early Jesuit missionaries record presentations of wampums that took the form of large circular discs that invoked the power of the sun, the ultimate source of illumination. In a presentation made during the 1650s, for example, the speaker stated that one such disc was being presented to ‘dispel all darkness from our councils and to let the Sun illumine them’. Only a few circular wampums have been preserved, one of which, in St Petersburg’s Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, is a round gorget or neck pendant of purple beads with an inlaid circle of white beads marked by the four points of the cardinal directions.

By far the majority of wampum belts were, however, woven rectangular bands that were carried draped around the neck and thus termed ‘colliers’ by the early French colonisers. To present a belt a speaker suspended it from his outstretched hand while explaining its meaning. Wampum belts translated the richly metaphorical imagery of Indigenous rhetoric into visual forms that are among the most creative inventions of the intercultural ‘middle ground’ – to use historian Richard White’s phrase. In regions where diverse Indigenous and European nations jostled against each other and competed for trade, land, and resources, wampum functioned as an innovative and effective strategy for mediating the ever-present possibility of violence. Pre-contact archaeological sites yield primarily small, disc-shaped beads – for without metal drills the production of cylindrical shell beads was a laborious process. Once European trade began, Indigenous people who had access to marine shell in what is now southern New York State and New England began to produce cylindrical beads in quantity. Settlers in New Jersey later established small factories for the production of wampum, further increasing the supply. The majority of the beads produced were white and were made from the inner spiral core of North Atlantic channelled whelk shell, while purple beads were made in smaller numbers from the rims of the quahog or Western North Atlantic hard shelled clam.

Wampum string made by a Moratico or

Rappahannock maker, Virginia, and donated

to the library of Canterbury Cathedral by Canon John Bargrave in 1676. Courtesy Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library

By the mid 17th century wampum had become the most important commodity in north-eastern North America. The desire of Indigenous trading partners to acquire wampum motivated them to procure the beaver pelts that were all-important to European traders, and the supply of wampum also helped to solve the problem of the chronic shortage of currency in the North American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries. It is therefore not surprising that when wampums arrived in early European curiosity collections they were identified as a form of money. When Canon John Bargrave made an annotated list of the contents of the cabinet of curiosities he was donating to the library of Canterbury Cathedral in 1676, he described the string of shell beads collected 20 years earlier in the Virginia colony by the Reverend Alexander Cooke as: ‘The native Virginian mony, gould, silver, pearle […] The black that is the gold. The name forgot. The long white their silver called Ranoke. The small white their pearle, called Wapenpeake.’ This inaccurate translation between different regimes of value is representative of the many misunderstandings of Indigenous thought worlds that took root early in the contact period. Yet Canon Bargrave’s string also comes down to us as a rare example of transition between pre-contact disc shaped beads and the cylindrical beads that had almost supplanted them.

The demand for wampum beads was also increased by the ongoing need to produce the large numbers of belts critical to contact-zone diplomacy and the formation of military alliances. Europeans required them to present in the councils in which they negotiated the alliances with Indigenous nations critical to success in the almost constant wars for dominance in North America. Indigenous nations needed belts for the same purposes as well to negotiate access to resources in territories held by other Indigenous nations as they were pushed west by expanding settlement along the coasts. This diplomatic culture generated tremendous political and artistic creativity. Arguably, the need to communicate across linguistic barriers stimulated the invention of a graphic language that drew on existing geometric and figurative symbols and created an increasingly elaborate pictorial iconography that could communicate even more clearly across linguistic and cultural barriers.

Three examples must serve to represent the large and varied corpus of belts that were made by and exchanged with Indigenous nations throughout north-eastern North America and the Great Lakes. The Dish With One Spoon wampum was exchanged among Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee nations, often traditional enemies, who agreed to share resources in lands extending from the eastern Great Lakes into southern Quebec. Its central image is a simple cruciform shape that represents the land as a single shared bowl out of which all would eat with the same spoon. This belt, too, has been periodically renewed and its contemporary relevance made clear. As Métis historian Karine Duhamel comments, it stands not only for the use of land, but also for its protection: ‘All participants in the agreement [or treaty] had the responsibility to ensure that the dish would never be empty by taking care of the land and all of the living beings on it.’

The innovative potential of wampum belts is illustrated by two other belts. In 1674, Huron-Wendat Catholic converts in Quebec incorporated Latin letters spelling out ‘Virgini Pariturae Votum Huronum’ (‘Gift from the Hurons to the Virgin who shall give birth’) into a large belt they sent to Chartres Cathedral along with the text of the speech that voiced their needs. A still more elaborate iconography is displayed by a belt known as the Two Dog wampum. It was probably made between the 1720s, when encroaching settlement caused a group of Kanienkehaka to relocate their village near Montreal westward to present-day Kahnesetake – and the 1780s, when Chief Aughneetha presented it to colonial authorities in defence of their rights to the new lands. The white line extending across the bottom marks the length of their land, he explained, while the figures with joined hands represent their loyalty to the Catholic faith, symbolised by the central cross. At the two ends two outward-facing dogs guard the boundaries of the land and give warning of interference. Like the Two Row and the Dish With One Spoon, the Two Dog belt retained its agency despite its removal to a museum and the misrepresentation of its meaning by the museum’s founder. As Jonathan Lainey has found, David Ross McCord gave the meaning of the row of figures as a ‘white man and Indians with hands joined thus leading the Indians in the paths of righteousness which is the white line under their feet’. In recent years, however, community members have presented it as evidence in a court of law to defend their land rights yet again. That the inventiveness and pictorialism illustrated by the Chartres and Two Dog belts remains a living tradition is well illustrated by the rich array of animals and human and supernatural beings that populate a much more recent belt, created by contemporary Wampanoag people for display in museums in the UK during 2021 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the voyage of the Mayflower (at the Box, Plymouth, until 11 July, then other venues).

The role wampums continue to play as authoritative evidence of historical agreements is owed to Indigenous wampum-keepers who have preserved the details of important agreements with great accuracy across the centuries, transmitting the readings of belts from generation to generation. When used in diplomatic and political contexts, presentations of wampum are collective affirmations of statements and commitments that have been made, somewhat like the official seals used by Europeans to certify the authenticity and enduring validity of important documents. As the website of the Onondaga nation explains, ‘When a string of wampum is held in a person’s hand, they are speaking truthfully.’ A community’s wampums constitute its historical archive. As the French Jesuit Joseph-François Lafitau wrote in the early 18th century, the Haudenosaunee among whom he lived made ‘a local record by the words which they give these belts, each of which stands for a particular affair’. ‘These belts,’ he explained, ‘are varied and the purple and white cylinders so disposed and intermingled that they all represent different things.’

Lieutenant John Caldwell (c. 1780), unknown artist (British school). Museum of Liverpool

Wampums entered European cabinets of curiosities soon after contact and found their way into early museums. Some were brought back by military officers such as Lieutenant John Caldwell who had participated directly in the process of alliance-making. On his return to England the adventurous young military officer had himself painted wearing the magnificent clothing in which he had been reclothed during the ceremonial adoption that made him a member of an Indigenous kin group – with attendant responsibilities to support it – and that often formed part of the diplomatic rituals. He holds out a wampum belt as he would have presented it in the formal council while affirming the commitments it represented. That belt is now lost, as are the meanings of many belts whose entry into museum collections detached them from their contexts of communal memory and the official documentary records kept by European negotiators. During the heyday of ethnographic collecting from the mid 19th through the mid 20th centuries, wampums continued to be much sought after by modern museums and private collectors. As communal property, however, they were usually acquired from people who did not have the right to sell them. In recent decades Indigenous claimants have successfully repatriated wampums from major museums in the United States and Canada. Research and repatriation led by Indigenous scholars and knowledge-holders are gradually reconnecting the belts with their orally transmitted histories and reactivating their meanings.

TwoRow II (2005), Alan Michelson. Photo: © Alan Michelson

Today, in addition to the ongoing renewal of wampum belts, a number of works by contemporary artists offer profound commentaries on their current poetics and politics. In Mapping Iroquoia: Cold City Frieze, Onondaga photographic artist Jeff Thomas has mapped the territories of the original five Haudenosaunee Nations on to both the Hiawatha belt that represents the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and an urban landscape made up of romanticised monuments to a ‘vanishing race’. And in his video installation TwoRow II (2005), Kanienkehaka artist Alan Michelson renders the two banks of the Grand River that separates the Six Nations reserve in Ohsweken, Ontario from the settler lands on the opposite shore as two bands of images, tinted purple, that stream in opposite directions across the white screen. Although the purple rows remain parallel they pull against each other, expressing the tensions that continue to inform relations between Indigenous and settler nations. The bitter fruit of four centuries of misunderstandings and broken promises, these tensions await the peacemaking work represented by wampum diplomacy.

‘Wampum: Stories from the Shells of Native America’, part of the Mayflower 400 programme, is at the Guildhall Art Gallery, London until 5 September.

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.