From the November 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The 19th century did much to mythologise Florence and its art. Conjure the spirit of Stendhal swooning in Santa Croce, submit to Ruskin organising your Mornings in Florence, or linger over Henry James’s evocations of the ‘Florentine character’ in his Italian Hours. But perhaps a better guide might be a lesser-known female writer who knew the city’s artworks more intimately than most of her contemporaries. Violet Paget lived in the city from the 1870s until her death in 1935 and was, in James’s words, ‘far-away the most able mind in Florence’. Known by her pen name Vernon Lee, which encouraged ambiguity about her gender, she wrote numerous studies on Renaissance art and culture, as well as supernatural tales and travel essays which vividly conjured the ‘spirit of place’ she detected in living landscapes.

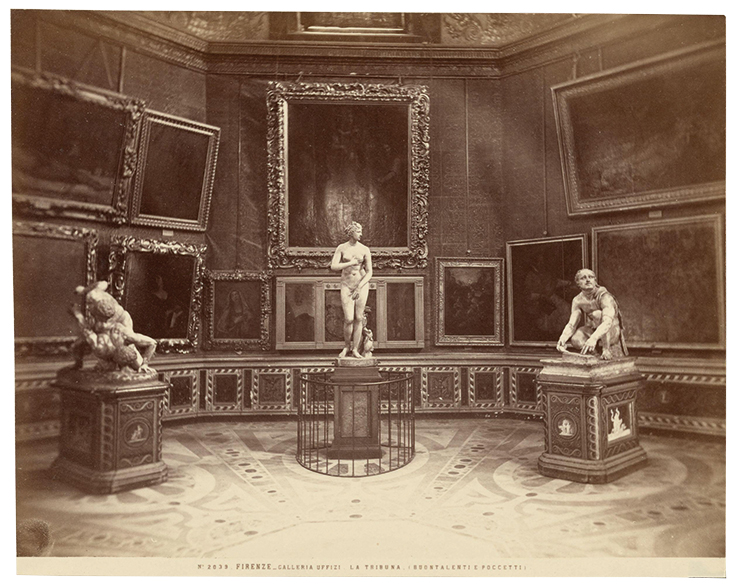

As a writer, she came of age as a disciple of Walter Pater, but she sought to extend the inquiries he had set out in his influential Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873), which asserted the significance of the individual’s subjective response to works of art. Lee would ask herself, ‘What is a work of art? What does it do for us, or rather, do with us?’ as she haunted the museums and galleries of Europe. In the late 1880s she began to develop innovative practices for investigating the psychological and physiological effects of art on the body. Lee worked in collaboration with her close companion, Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, who had trained as a painter and according to Lee displayed heightened physical receptivity to works of art. First-hand encounters in the museums, galleries and churches of Florence were at the heart of the women’s research as they recorded bodily changes such as quickening of breath or raised temperature in response to certain sculptures and paintings. As Lee affirmed in 1911, ‘My aesthetics will always be those of the gallery and the studio, not of the laboratory.’

Lee was ahead of her time in anticipating modern museology and its emphasis on viewer response. In recent years museums and galleries have given increasing thought to visitor experience, redisplaying collections and inviting sensory engagement through sound, immersive experiences, and even taste. Lee understood the multisensory nature of viewing art, and sought to reconnect art, life and the body. Over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, we have become more attuned to our bodies and yet more estranged from physical encounters with artworks, even as digital interventions provide a different mode of encounter. What does Lee’s approach have to offer us today?

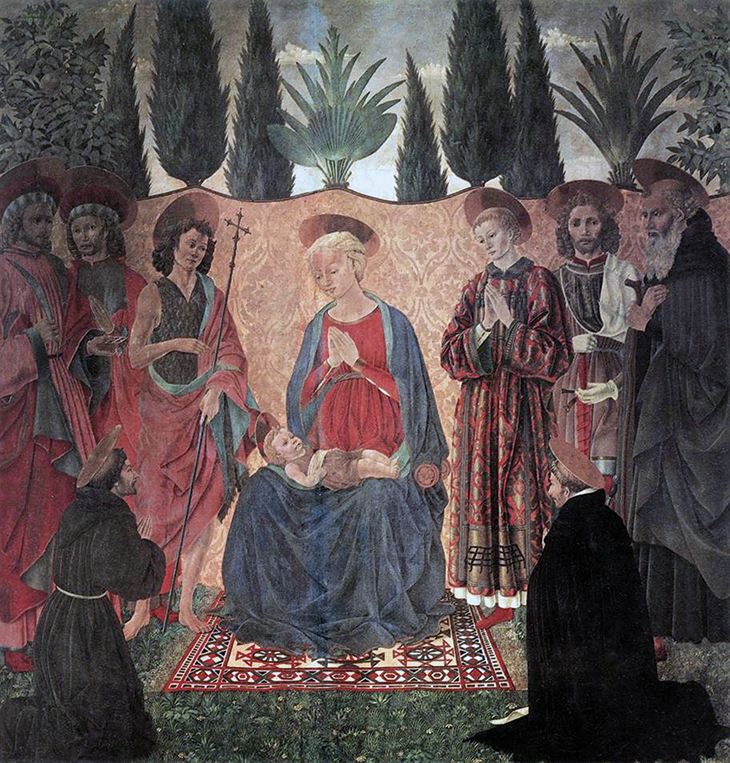

Madonna and Child with Saints (c. 1454), Alessio Baldovinetti. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Few writers have charted the nature of their physical encounters with paintings and sculptures as intimately and precisely as Lee in her ‘Gallery Diaries’. Written at the turn of the 20th century in a hybrid of autobiography, psychology and aesthetic commentary, they trace her shifting responses to form, line, rhythm and colour on her many visits to study works in the Uffizi or the Bargello, among other galleries. Sections of the diaries from the winter of 1903–04 in Florence chart her ‘observations in the museums with especial reference to rhythmic obsessions, palpitations and aesthetic responsiveness’. Take one occasion, on a winter’s day at the Uffizi, when she records a synaesthetic journey taking in, first, Baldovinetti’s Madonna and Child with Saints:

Coming up the stairs (no palpitations) I discover a tune in my head and which I am actually singing or whistling […] It is Allegro of a Mozart Sonata. […] I walk quickly and stop at the Baldovinetti Madonna and Saints. I know I like the picture and immediately get into a superficial examination. Pleasure comes suddenly with perception of bearded saint’s white gloves. I then begin to see the relief, go into the picture. Light bad; I can’t see whole well. Left-hand corner; I take pleasure in bearded man and much bulk pleasure in Saint Lawrence and his very beautiful dress, and in his flat but solid existence. Am a little worried by his wrong spatial relation to bearded man. . . . Saint Anthony (though I spotted him at once, saying how like Baron A– F–) is difficult to look at, all because he is without solidity […] A sort of raising of my hat and scalp and eyebrows seems necessary to see this picture; otherwise it is swimmy. By the way, the lilac and crimson give me a vivid cool pleasure, like taste.

And on to Cosimo Rosselli’s Magi, where colour similarly attracts her; but by the time she reaches the Venetian Room she finds herself (and who hasn’t felt this after hours in a museum) ‘tired, bored, disinclined to look at anything’, until, arriving in front of Veronese’s Sophonisba, she is seized by a ‘physical [pleasure], located almost in my mouth’. Melodies would often accompany these encounters – Lee was a passionate musicologist, and described ‘secretly “sampling” statues and pictures with “tunes”’.

The Tribuna at the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photograph by Fratelli Alinari (founded in 1852). Photo: BG/OLOU/Alamy Stock Photo

Lee’s experiments in the galleries were not as eccentric as they might first seem. At the end of the 19th century, many artists and writers were shaping debates about the experience of art and its relationship to physical and moral health. They were confronting new theories of evolutionary science promoted by figures such as Grant Allen and Herbert Spencer who explained the experience of beauty and perception in evolutionary terms. In recent years, the work of pioneering contemporary visual neuroscientists, notably Semir Zeki, into the cerebral cortex’s response to artworks, seems to confirm the links Lee was making between art and the brain as her physiological aesthetics broke down entrenched ideas of a split between mind and body. For Lee the experience of art was visceral, often violently registered in the body and translated into vivid metaphor. She studied and began to correspond with leading psychologists and philosophers, and her investigations drew on theories of the emotions developed by William James in his Principles of Psychology (1890), and on the work of German physiological psychologists Karl Groos and Theodor Lipps. She has been credited with introducing Lipps’ concept of Einfühlung or ‘empathy’ into English in her ‘Gallery Diaries’. An attempt at ‘feeling into’ an object or person was at the heart of her collaborative approach. As she summed up her own ‘Aesthetics of Empathy’: ‘the work of art requires for its enjoyment to be met halfway by the active collaboration of the beholder, or, I may add, the listener and the reader’.

In their co-authored essay of 1897 ‘Beauty and Ugliness’, Lee and Anstruther-Thomson had defined the distinguishing criteria for great works of art as prompting ‘feelings of vivid fellowship’ and making the spectator ‘feel more keenly alive’. They suggested that great works of art have a detectable atmosphere, or ‘climate’, which permeates the air around them, and which the viewer may enter or find ‘encompassing’ them. In one evocative reading of Catena’s painting of Saint Jerome (now in the National Gallery in London) they identify the painting as giving ‘to the air which we inhale a sort of exhilarating power; and the special colour quality of coolness’ so that it ‘awakens […] a feeling of temperature similar to that of a spring day’. What variations in aesthetic weather might we experience as we walk through re-opened galleries at home and abroad, and what effect might they have on our own psychological climate?

Vernon Lee photographed in 1902 by Ernestine Fabbri in her study at Villa Il Palmerino in Florence. Photo: akg-images/Rabatti & Domingie

In 1889, Lee and her family moved from the centre of Florence to Villa Il Palmerino – on the very edge of the city, with the Etruscan city of Fiesole and the woods of Vincigliata rising above it. Like generations before her fleeing the plague, Lee had sought out a villa in the hills above Florence partly to escape an outbreak of cholera in the city’s congested inner walls. Her travel writings, written around the same time as she was formulating her physiological aesthetics, offered another form for embodied response, evoking her deep sense of connection with the Tuscan landscape surrounding her home. As she urged in her book of essays on the spirit of place, Genius Loci (1899), we need to rethink our relations with places: certain localities ‘can touch us like living creatures’ and we can form with them ‘friendship of the deepest and most satisfying sort’. If, as she believed, such relations to places could enrich one’s connection to the world, then deeply sensory relationships – one could even say friendships – with artworks made familiar by frequent visits and intense physical response could do something similar. Travelling in Lee’s footsteps through her writings around Florence we uncover a different character to the Renaissance city. Statues, paintings and architecture beckon the viewer to meet them in a mysterious overlapping of past and present, the ‘vivid fellowship’ that constitutes aesthetic experience.

Portrait of Vernon Lee (1889), John Singer Sargent. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

At Il Palmerino – one of her most beloved of localities – Lee created a salon where artists and writers such as Henry James, John Singer Sargent and Edith Wharton could gather and share ideas. A friend to Lee from childhood, Sargent captured something of her alertness and readiness for conversation and debate in his oil of 1881 and a pencil sketch of 1889. Unlike many of her fellow expatriates, Lee spoke fluent Italian and formed strong bonds with Italian literary figures such as Carlo Placci and Tuscan artists such as the Macchiaioli painter Telemaco Signorini. The creative and cosmopolitan spirit that she fostered at Il Palmerino imbued her writing, from fiction to aesthetics to pacifist manifestos. The impulse of Boccaccio’s storytellers from the Decameron who, five centuries previously, had escaped to the Florentine hills to seek refuge from the plague, must have felt as familiar to Lee as it does in our own time. As I experienced in living through last year’s lockdown in Italy, the spirit of Lee’s salon lives on: the current owners of Il Palmerino run their house as an artist’s residency, with exhibitions where possible, and music and poetry in the garden.

By the end of the century, Lee had become increasingly dissatisfied with the mantra of ‘art for art’s sake’ popularised by many of Pater’s decadent followers as his defining message. In her book Renaissance Fancies and Studies (1895) she pledged herself to ‘art, not for art’s sake, but art for the sake of life – art as one of the harmonious functions of existence’. The first decades of the new century would in fact be characterised by disharmony: dominated by political upheaval, war in Europe and the Spanish Flu in its cruel aftermath. In these years Lee increasingly sought a socially productive and practical role for art. Nevertheless, she retained her belief in its power to enhance life and physically rejuvenate the body.

Lee knew what it meant to spend periods of time estranged from the city and the artworks she loved. Following a visit to England in 1914 she was prevented from returning to Florence due to the outbreak of the First World War and spent most of the war in London. She became an increasingly outspoken – and as a result ostracised – critic of the war, publishing her pacifist satire The Ballet of the Nations in 1915, which envisioned war as a diabolical dance. Her staunch pacifism partly explains why her popularity faded in the early 20th century.

What might we learn from Lee’s sense of the profound relationship between art and the physical and spiritual health of the body? After more than a year warring against a virus and unable to walk freely into galleries, can we recover Lee’s idea of ‘art for life’s sake’? As we slowly reacquaint ourselves with collections out of sight for too long, her faith in art’s power to harmonise and rejuvenate seems all the more poignant.

Vernon Lee (1881), John Singer Sargent. Tate collection Photo: © Tate

But if the galleries close again, Lee reminds us not to despair. In her ‘Tuscan Notes’ on art and the country, she suggests that the best place to get to know the ‘special artistic temperament’ of a school of painting may in fact be ‘in the fields’. She advises that we might learn more from an afternoon spent on the hillside, savouring its sensory and atmospheric conditions, ‘its particular taste of air, its particular line of shelving rock and twisting road and accentuating reed or cypress in the delicate light’, than from hours inside gazing at Signorelli and Lippi, or Angelico and Pollaiolo, ‘all telling one different things in different languages’. Her strong sense of the need to understand the landscape from which an artist has originated in order to truly gain insight into their work underpinned her essay on the ‘Imaginative Art of the Renaissance’. She relates the experience of walking along the river near Careggi in Florence ‘with its memories of Lorenzo dei Medici’, where a strip of grass whitened with daises brings to mind ‘the remembrance of certain early Renaissance pictures: the rusty, green, stenciled grass and flowers of Botticelli, the faded tapestry work of [Fra] Angelico’. Walking in their footsteps, she feels a kinship with these artists from four centuries ago and her visual memory of their paintings makes the present more vivid: ‘the greenness greener, the freshness fresher, of that real grass and those real trees’.

Lee knew that the viewer could feel themselves permeated by – and connected to – works of art in ways that were hard to describe. She also knew that this experience could be sustaining in difficult times. As she wrote of the ‘world of enchantment’ created by Botticelli in the Primavera, ‘I fancy one remains in it even when not looking.’ Lee’s sense of the merging of self and works of art in ‘vivid fellowship’ is more important than ever today.

From the November 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.