From the January 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1583 the Venetian senate toyed with the idea of dismantling the well-preserved Roman amphitheatre of Pula, in Croatia, and reconstructing it in the middle of Venice. Happily, the scheme was rejected – but it speaks volumes about La Serenissima’s relationship with antiquity. Among the myriad ways in which Venice is an unusual place, one is that it is a great Italian city with no Roman past. It had to acquire its layers of antiquity – just as it had to steal the body of its patron saint from Alexandria. Attune your eyes to this collage-like quality as you wander Venice’s streets and squares, and you see examples of these (mostly looted) acquisitions everywhere – from discs of coloured marble sliced from Roman columns and set into facades to, my personal favourite, the porphyry tetrarchs huddled together on the south-west corner of the Basilica di San Marco, snatched as booty in the Venetian-led conquest of Constantinople in the 13th century.

In Venetian Renaissance sculpture particularly this produced ‘a special climate’, says Philippe Malgouyres, curator in the department of decorative arts at the Louvre. ‘Its relation to antiquity is not what it was in Renaissance Florence, for instance, where artists were looking to the antique to find inspiration for the expression of life in their art. Venetian art is colder in tone, perhaps, and more concerned with a correctness of shape – perfecting the antique rather than being inspired by it.’ Malgouyres is speaking to a group of journalists gathered at the Ca’ d’Oro, one of the Grand Canal’s most distinctive palazzos, some weeks before many of the works in its collection travel to Paris for an exhibition he has curated at the Hôtel de la Marine, home of the Al Thani Collection. ‘Ca’ d’Oro: Masterpieces of the Renaissance in Venice’ (30 November 2022–26 March) coincides with the start of a two-year renovation project at the palazzo, funded by Venetian Heritage (and a number of private donors).

View of the facade of the Galleria Giorgio Franchetti at the Ca’ d’Oro on the Grand Canal in Venice. Photo: Matteo De Fina; © Galleria Giorgio Franchetti alla Ca’ d’Oro, Direzione regionale Musei Veneto – reproduced by permission of the Ministry of Culture

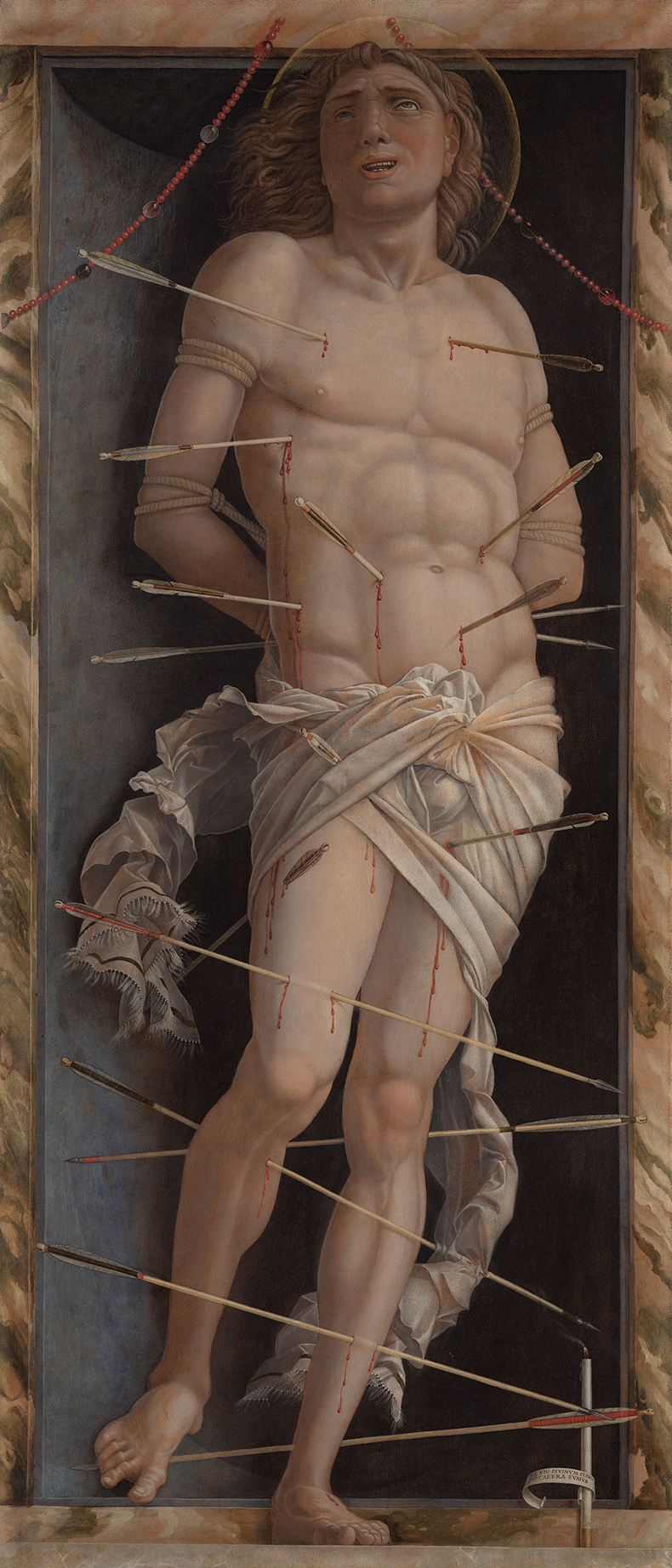

Built between 1420 and 1434 for the merchant Marino Contarini, the Ca’ d’Oro is often mentioned in the same breath as the Palazzo Ducale as an outstanding example of Venetian gothic. Not for nothing was it admired and drawn by Ruskin, who in 1853 wrote of ‘a noble pile of very quaint Gothic’, while lamenting the fact that the palazzo was ‘once superb in general effect, but now destroyed by restorations’. Around half a century later Baron Giorgio Franchetti, a Turinese industrialist, bought the palazzo, restoring (and amplifying) much of its late gothic character. Ruskin would surely have approved of the fact that Franchetti tracked down and reinstalled the palazzo’s marble wellhead, carved by Bartolomeo Bon in 1427–28 and sold by one of the building’s previous owners. He would have been less pleased, we can imagine, with the nascent collection of Renaissance art that Franchetti installed, the star of which was and is Mantegna’s San Sebastiano from the 1490s. ‘This was the great coup of Franchetti’s life as a collector,’ Malgouyres says. Attesting to that is the marble-lined anteroom the baron designed especially for the painting on the first floor – essentially a chapel without an altar, but with Mantegna’s arrow-skewered saint as altarpiece; aesthetic veneration is the point here.

Franchetti selected ancient statues from the Museo Archeologico to supplement his own collection, which he intended to leave, along with the palazzo itself, to the Italian state. After the Ca’ d’Oro opened to the public in 1927, five years after Franchetti’s death, the gallery continued to acquire works from various state-run properties in Venice, with a focus on Renaissance sculpture. One of the masterpieces of the collection – and one of the most striking interactions with antiquity – is Tullio Lombardo’s Double Portrait from c. 1490–99. Carved in high relief so that its enigmatic couple emerge almost in the round from their marble panel, this twist on the Roman funerary monument is somehow both subtle and arresting. ‘Tullio is the most emblematic sculptor when it comes to the antique style in Venice,’ Malgouyres says, ‘with this attention to the accuracy of detail’ – but there are departures, too: the woman’s breasts bare above the cut of her dress; both figures’ mouths open sensuously – dopily, even. There’s a dreamlike atmosphere here that has drawn comparisons with Giorgione’s paintings just a few years later.

Saint Sebastian (1490s), Andrea Mantegna. Galleria Giorgio Franchetti all Ca’ d’Oro. Photo: Matteo De Fina; © Direzione regionale Musei Veneto – reproduced with the permission

To put some of the Ca’ d’Oro’s collection in context, Malgouyres leads us to the basilica of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, whose structure was completed around the same time, its style another last hurrah for Venetian gothic. Elements from the church of Santa Maria dei Servi, demolished in the Napoleonic era, found a new home here, notably Tullio Lombardo’s grand funerary monument for Doge Andrea Vendramin (whence came the life-size marble figure of Adam which gave ‘the Fall’ a whole new meaning – and conservators an unprecedented challenge – when it smashed to the ground from its pedestal in the Met in 2002). At the back of the basilica, Tullio’s father Pietro’s monument for another doge, Pietro Mocenigo, is more Roman triumphal arch than Christian meditation on the afterlife.

In the church of San Giovanni Crisostomo we find another homage to antiquity by Tullio Lombardo: a marble altarpiece depicting the Coronation of the Virgin, in which the assembled apostles, their heads aligned frieze-like at the same level, resemble figures on a Roman historical relief, or sarcophagus. The artist has carved his name in Latin under the figure of Christ, leaving no room for doubt over its authorship.

By contrast, over the entrance to the jewel box of a church that is Santa Maria dei Miracoli, the sculptor of a Virgin and Child installed there has included a plaque inscribed not with his own name, Giorgio Lascaris, but with an adopted one: Pyrgoteles, recorded by Pliny the Elder as the only gem carver permitted to execute Alexander the Great’s portrait in emerald. ‘We don’t even know of any work by Pyrgoteles,’ Malgouyres explains; ‘it’s just a name from Pliny. So this relationship with the ancient past could operate on a very personal level. It really speaks to the way people here were striving to reach the heights of these great artists from antiquity.’

From the January 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.