This is a young man’s book, written by somebody aged 73 and here reviewed by someone 13 years older. If you have ever wondered, as I have, about the age of the art historian you are reading, you can Google the scholar and roughly deduce it from the year of their PhD. Or, more interestingly, you can infer it from the education they received. The point is not his or her absolute age, but rather the scholar’s degree of seniority in relation to the training he or she underwent, and ability to keep themselves out of the argument – an injunction I have already twice ignored.

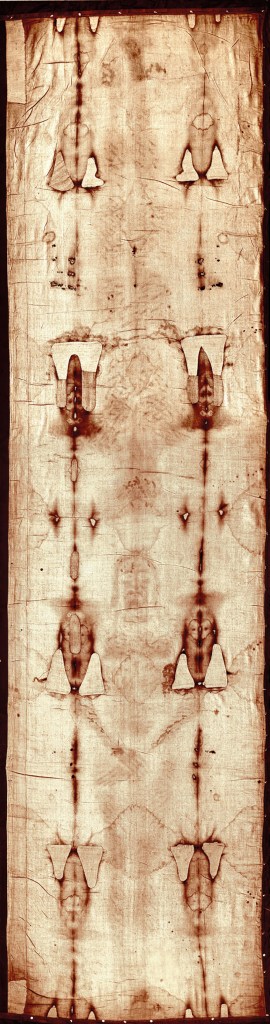

The Turin Shroud (mid 14th century). Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, Turin

In his first chapter, Vikan, ‘[a] towering figure in the art world’ according to the publisher’s blurb, describes how nearly 40 years ago he came across a facsimile of the Turin Shroud advertised (for $12) in a copy of the National Enquirer. (He’d found the tabloid crumpled in a snow bank as he walked to work at Dumbarton Oaks, Harvard University’s Center for Byzantine Studies in Washington, D.C.) The imitation was on linen, reproducing the material of the original as prescribed in all four Gospels. It would, the advertisement promised, ‘bring you everything in life you desire and so rightly deserve’.

It may not have been this promise that tempted Vikan to keep hold of the paper. At that time, as well as long before and afterwards, he saw his real job as being that of whistle-blower where fakes were concerned. The title of his day job at Dumbarton Oaks was ‘Associate for Byzantine Art Studies’ and in March 1981, when the advert miraculously appeared to him, he was preparing for the following year an exhibition with the title ‘Questions of Authenticity among the Arts of Byzantium’. Undeterred then and later at the Walters Art Museum, where he became the director, he pursued his passion for hoaxes, lecturing and writing about the subject of this book’s title. In fact, this could be called The Shroud and I, for it bypasses the huge and sprawling literature (mostly online) on such matters as the transmission of the object to Turin. As a trained historian of Byzantine art Vikan uncovers the Orthodox origins and artistic expressions of the idea of a holy image before turning to what was literally the invention of the shroud in medieval Lirey, today a hamlet of some 89 people a few miles south of Troyes, the capital of Champagne, whose local beverage he put to good use.

As a medievalist, Vikan illustrates but does not discuss the famous canvas of about 1540, attributed here to Giulio Clovio, a pièce justificative that purports to show the first use of the object at Jesus’s deposition from the Cross, before it too was raised to heaven, and a painted exposition of why the legendary relic shows both the front and back of Christ. With lots of help from his scientific friends and a pilgrimage to Lirey, Vikan demonstrates how the shroud was made in the mid 14th century. The 20th-century medical knowledge involved is no less relevant than the medieval history. Vikan explains why the nails appear on the image to be driven through Jesus’s wrists rather than the palms of the hands (the flesh would tear and the body drop to the ground); he also attributes the excessively long arms suggested by the shroud not to Marfan syndrome (the genetic disorder from which Abraham Lincoln is thought to have suffered) but to the artist’s wish to cover Christ’s groin. In short, the Turin Shroud is a contrivance, a work of art, not something ‘made without hands’, as the Byzantines conceived of their most holy icons. Nor, of course, is it part of standard Catholic iconography as is Manet’s Dead Christ with Angels (1864) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the genitals are covered with a loincloth and the stigmata are prominent features of the dead man’s palms. For a Byzantinist, Vikan is an acute interpreter of images generated in the wake of the Black Death. Ingeniously, for example, he explains the reason for the popularity of St Sebastian: a panel in the Walters from the last years of the 15th century shows the saint interceding for the victims of the plague, his body pierced by arrows – a perfect emblem for humankind being afflicted by an epidemic from which it is ultimately saved by God.

Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague-Stricken (1497–99), Josse Lieferinxe. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Such credence is of course remote from the concerns of those who have essayed several mistaken efforts to carbon-date the shroud, and the loonies who to this day constitute STURP (the Shroud of Turin Research Project) and publish a journal in the effort to make their case. For my money, Vikan’s book, unfurling this famous cloth with its accreted myth, is one of the most stimulating things I have read on the shroud. There are mistakes, mostly in the captions, in French (‘Mont Sante Victoire’), German (‘Andachsbild’) and Italian (Giulio ‘Clavio’), but these hardly matter. It has all the twists and turns of a classic detective story, illuminated by Vikan’s intelligence and willingness to admit – to us and to himself – where over the years his hypotheses have been wrong, and what to do to check and correct them. The Holy Shroud is a work of empiricism in the service of both art and faith. As such it is very much a book for our times.

The Holy Shroud (c. 1540), attrib. here to Giulio Clovio. Galleria Sabauda, Turin Photo: © akg-images/De Agostini Picture Library

The Holy Shroud: A Brilliant Hoax in the Time of the Black Death by Gary Vikan is published by Pegasus Books.

From the November 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.