On Friday 20 January, artists, critics, scholars, and curators around the United States will take part in a day-long Art Strike in response to the inauguration of Donald Trump. Many commercial galleries have decided to close for the day in solidarity with the strike while numerous museums plan to offer free admission and related programming. Among the many protests and demonstrations that will take place across the country, the Art Strike presents an important opportunity for members of the art world, as well as those who care about the arts, to consider how the production, reception, distribution, and display of art can register and inform aspects of social life (questions, it could be argued, that were equally crucial, if too often overlooked, in the pre-Trump era).

If the act of going on strike has traditionally functioned as a way of withholding labour in order to focus attention on critical issues and produce actual change, one should ask: What is the labour being withheld? What are the issues that should be foregrounded? And what sort of changes are demanded? Beyond the symbolic power of a day of ‘non-compliance’ and protest, an Art Strike dedicated to the redirection of artistic practices – whether creative, curatorial, or even commercial – in response to the feared imperilment of individual liberty and social equality that a Trump presidency might inaugurate could also be a much more sustained endeavour in which artists and institutions will have to ask themselves on a daily basis how their actions articulate what is most worthy of the category of art, and as a corollary what values are worth defending and declaring as valuable in the world at large.

Defined as a human activity that registers, questions, and influences social values, art can be understood as a realm of human activity where people can come together and consider what matters. That the claims and values surrounding art are contestable has been considered one of its greatest virtues, central to art’s role as a paradigm for human activity that, at least in its ideal state, is not instrumentalised or pursued solely for profit. This facet of art seems especially crucial at a moment when increasing aspects of contemporary life – including some of the pillars of civic life: healthcare, education, and even interpersonal communication—are increasingly monetised and privatised.

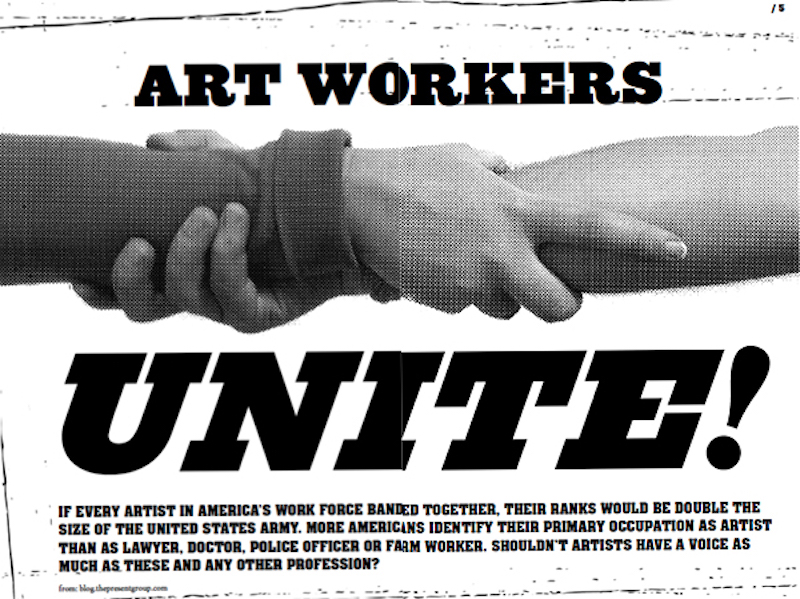

Image from Artist Bloc No. 1, a zine created by a group of Bay Area artists, scholars, and writers in 2011

Societies that are relatively stable are able to, and often do, take these virtues of art for granted. In such milieu, artists and their audiences have the privilege to explore other aspects of art: questions of materials and the creative process, the various influences that inform the work, its movement across time and space, biography and form. But there are moments when it seems that the social role of art – its capacity to draw attention to critical issues in the world in which it is viewed – becomes crucial. Art in this respect serves as a site where a community can come together, where a community can in fact be formed, and consider what matters, what is worth talking about, what needs to be addressed.

For many of us involved in the creation, study, and preservation of art, the election of Donald Trump is an event that calls for a renewed commitment to the social role of art and art institutions. At a moment when many Americans – and members of the global community – are concerned about the protection of fundamental human rights and more particularly the nation’s guiding principles of liberty and equality, art institutions can take on the essential role of bastions for these values. Historically, art museums have served as the stewards of culture and art itself as a sort of barometer of a society’s well-being. It is precisely because of the sense of threat to civil liberties, to civic justice, and to constitutional law that arts organisations need to declare their dedication to a free and open discourse, a respect for cultural difference, and a responsibility for historical events and objects that may be endangered by ideological extremism, profit-driven motives, and an apparent presentism engendered by a 24-hour mediascape.

The #J20 Art Strike will be held across the US on Friday 20 January.