The stark white walls of the Serpentine Sackler Gallery are dotted with colourful eruptions, each contained within a 48 x 38cm canvas, the trademark format of the painter Tomma Abts. Their small size pulls the viewer in closer until we become intimately engaged with each concentrated schema. In their clearly delineated, geometric formations the works are superficially reminiscent of Constructivism, yet this comparison ignores the intrinsic incoherence of their structures, which collapse in illogical interruptions or trail off only to convulse again with new life. These works may appear ordered, but they have the lyrical, expressionist quality of a Kandinsky.

Comparisons with other artists may not, however, be all that useful. Despite winning the Turner Prize in 2006, Abts is something of a lone wolf in the art world. As the German-born, London-based artist told the Guardian the day after her win, ‘It [the Turner] used to be such a personality-based prize and I think that’s not appropriate necessarily, for art.’ Elusive about her life, Abts remains shielded by her work although we do know that she never went to art school, a fact that can only pique our curiosity about how she came to realise such a specific and solitary artistic vision. Works separated by a decade appear to be part of the same series, held together by repeated motifs and a shared language of line and shape.

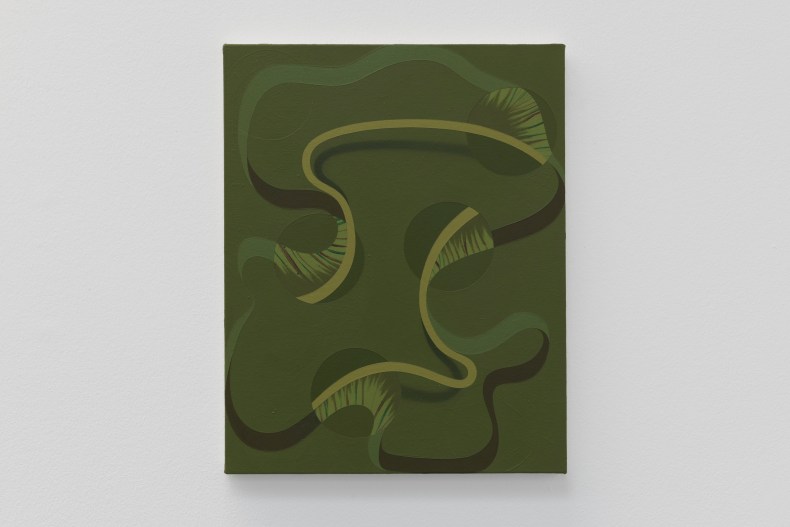

Lühr (2004), Tomma Abts, installation view at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London, 2018. © 2018 readsreads.info

This language relies heavily on colour, but it is equally determined by Abt’s precise layering of paint, which produces a map of visible ridges, areas of shading that introduce new dimensions of illusory space, a variety of surface textures reminiscent of collage and, at times, a canvas that has been pared or sliced in half. In Bilte (2008), an agile, frame-like structure projects quite sculpturally yet is entirely unembodied. Some of its bent limbs bear brighter patches of orange glow, as though just catching the light.

As overlaid planes unfold, the apparent relationship between foreground and background often does not correspond with the physical surface of the canvas, which has cut-outs for areas that seem illusionistically raised but have been built up with thicker layers of paint to describe the compositional structures beneath. In Weie (2017), long strips of semi-exposed canvas form ribbons that are laced across the length of the work; draped and suspended, they cast shadows over a bold red backdrop. Other works have quick flickers of figuration, such as the grassy tufts of the green-toned Lühr (2004).

As the eye roams, works that seem at a distance static and flat become living landscapes. This seems to be the result of Abts’ intuitive approach, in which she begins without source material or even a plan, but gradually allows the painting’s internal logic, or lack thereof, to unfold spontaneously. The resulting constellations are no more predictable for Abts than they are for us: ‘I can’t really ever say what it will look like or how it will finish or what will make it work. It’s a different idea or moment for each painting.’ Sierk (2012), which is striped with the muted brown and orange tones of a 1970s carpet, is unexpectedly animated by two curved projections that spring upwards and bend in disorientating directions.

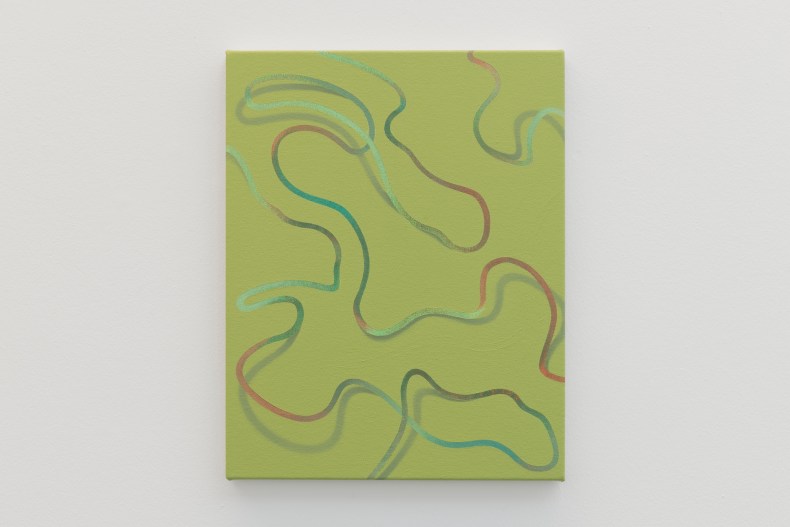

Lüür (2015), Tomma Abts, installation view at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London, 2018. © 2018 readsreads.info

There is a sense in which Abts has created seemingly infinite worlds. The multi-coloured tangle of loosely curved lines in Lüür (2015) could almost be a flyover from an unknown psychedelic sphere. Dako and Swidde (both 2016) are metal casts of painted canvases and each bears the same circular arrangement that beams out triangular rays. The monochromatic design is subtle, yet has a completely different effect depending on the material used. Swidde, in bronze, is like scorched earth, burnt a smouldering orange by the sun and marked by mysterious ancient imprints. The silver aluminium of Dako makes a far more new-age and industrial impression.

Dako (2016), Tomma Abts, installation view at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London, 2018. © 2018 readsreads.info

There is a contrast between the uniformity of Abt’s work overall and the way in which she relinquishes control over form and expression in individual paintings. The result is a succession of unbounded explorations carried out within a framework of tightly controlled variables. For this self-titled exhibition she has exercised the former by playing a significant curatorial role. Choosing a highly specific order and spacing for the paintings, she guides the viewer through a considered conversation about their similarities and disparities. This is Abt’s first solo show in the UK, and the largest of her career so far since winning the Turner Prize 12 years ago. It is long overdue.

‘Tomma Abts’ is at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery until 9 September.