From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

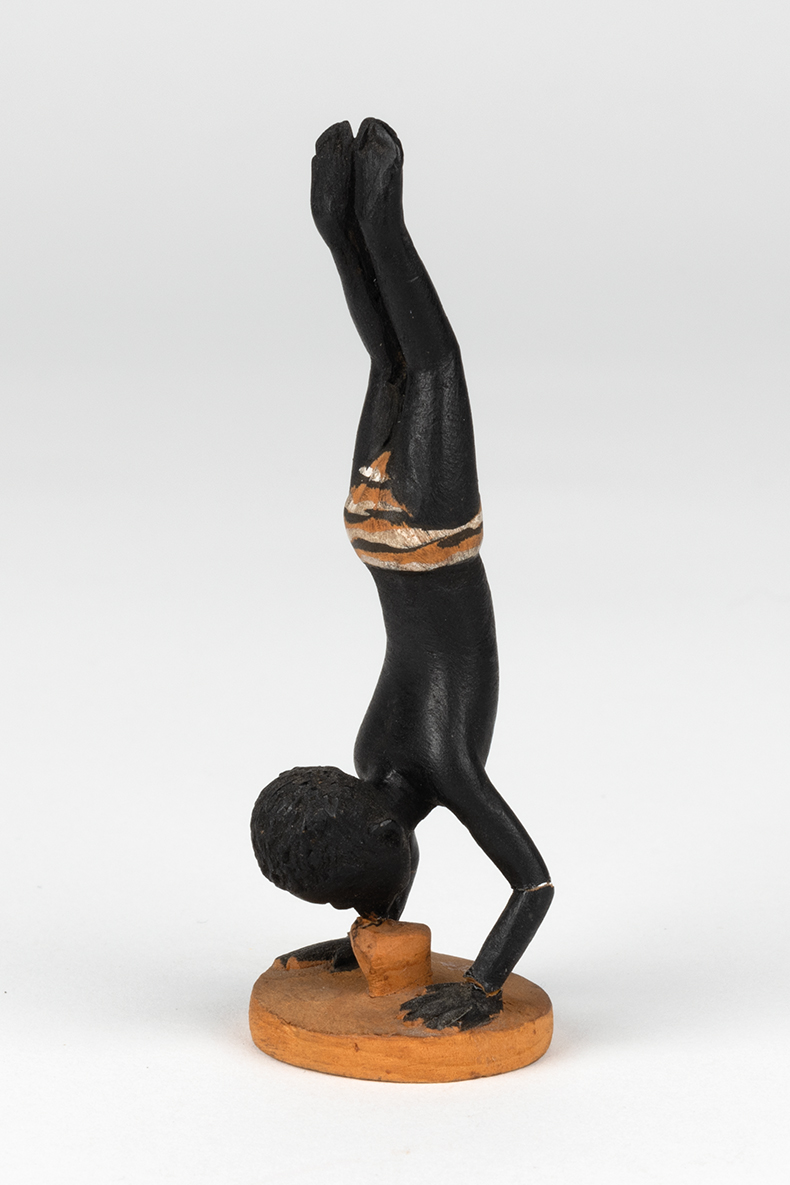

He has the pose and poise of a diver in flight. Legs and spine are in perfect alignment as he raises himself into a handstand that looks assured enough to last forever – which, in a sense, it might. This acrobat’s feat was captured in wood by the carver Justus Akeredolu in 1957. From the base of the platform on which he rests his chin to the tip of his toes, the boy spans just under 8cm. He has been carved out of a single thorn.

An unsigned article in the June 1938 issue of Nigeria magazine noted that thornwood carvings, of the style pioneered and passed down by Akeredolu during his years as a craft teacher at the Government School in Owo, were ‘much appreciated by Europeans’. They could be slipped into your pocket as keepsakes – and they have also slipped too often and too easily into that most maligned category of African art. For the historian of Yoruba art William Fagg, work made for the tourist trade was not only ‘without any merit’ – it was also directly responsible for ‘the degradation of carving traditions’ among the Yoruba. Such miniatures have also been given short shrift in the history of artistic modernism in Nigeria; anecdotal and unassuming, they are a far cry from the ambitious attempts to define a new national style in painting and sculpture, in the years before and after Nigerian independence in 1960, by the likes of the Zaria Rebels.

At the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, however, there is currently a rare opportunity to see a group of these carvings up close – part of ‘The Trembling Museum’ (until 19 May). The exhibition takes the writings of the Martinican philosopher Édouard Glissant as a rationale for digging out seldom displayed African objects from the museum’s stores and considering what it means to show them in a Western gallery space today. In two prominent display cases, works by Akeredolu – ranging from the acrobat to pipe-players, or men and families simply lounging around – are juxtaposed with those of George Craft Studios, active in Ibadan in the 1960s, allowing viewers to assess how the style changed as it passed down the generations. The latter are a little larger and more elaborate, with the makers no longer confining themselves to a single thorn. They have been thought by some – not least Frank Willett, an expert in Nigerian art who acquired many of these works during his time as director of the Hunterian – as lacking Akeredolu’s ‘delicacy of touch’, perhaps helping to cement the impression of this genre as tourist work, although the vignettes they present are no less vivid.

Figure of a boy (1957–58), Justus Akeredolu. Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow

Akeredolu happened upon his medium in the 1930s. He began by carving simple name-stamps on the large thorns of the silk-cotton tree, before giving these tools little handles in the form of human heads and realising in the process how apt the thorns were to supporting minuteness of detail. The exquisite figures he soon began to produce procured him a scholarship to study museum work in London in 1950, after which he returned to Nigeria to work as a restorer in the Antiquities Service. From that decade on he began to incorporate colour, juxtaposing the natural red, yellow or dark brown of the thorns with black ink for flesh. He continued carving, even after the loss of an eye in 1963, until his death in 1984. Akeredolu also produced paintings and sculptures of a larger scale that were recognised as contributions to Nigerian modernism in his day. Quite what he thought of his thornwood miniatures – jeux d’esprit, souvenirs for sale, or something more – is hard to say. But each of them bears his signature on its base, and perhaps the clearest mark of his success is that the style he invented outlived him. At the National Museum in Owo, a display opened in January of works by Akeredolu and his son Olulaja, who continues to practice and to advocate for the medium.

Taken together, the works of Akeredolu and his protégés comprise a panorama of everyday life in Nigeria as it modernised: Yoruba men and women at work with the hoe, or grinding meal, or scaling palm trees to collect fruit; riders of horses and bicycles and scooters; children at play; drummers in a groove; carvers, potters and hairdressers at their craft and scribes at their Qur’an. Yet they also hark back to long-established Yoruba traditions. In the elaborate superstructures of Gelede masks, the handles of swords or tools and the relief panels decorating palace doors, Fulani nomads from the north or colonial officers of the West have appeared in portraits both satirical and serious since the early 19th century – and local characters running the gamut from mischief-makers to dignitaries for many centuries more. Like the stunt of Akeredolu’s acrobat on his diminutive podium, perhaps these thornwood sculptures are above all a feat of balance – an unlikely equilibrium between tradition and modernity at the very moment in Nigeria when they were perhaps most radically opposed.

From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.