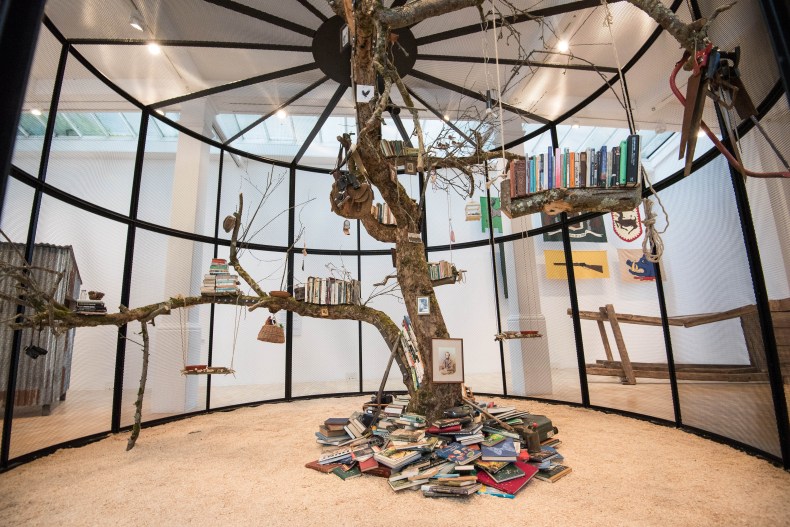

On entering Mark Dion’s exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery on a quiet, sunny Sunday morning I am met by the soft chirruping of zebra finches. Twenty-two of them currently inhabit a large aviary in the gallery as part of The Library for the Birds of London. Entering the aviary in small numbers, visitors observe the birds, which seem oblivious to their surroundings, (presumably) unaware of the witty play of books, images and objects that Dion has presented in their honour. A basket of wooden eggs sits next to a salt cellar, a series of bird-related postcards are pinned to the tree trunk.

Installation view of Mark Dion’s The Library for the Birds of London (2018) at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2018. Photo: © Jeff Spicer/PA Wire

‘There are no spectators, only participants,’ Mark Dion tells Iwona Blazwick in a conversation included in the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition titled ‘Theatre of the Natural World’. To a viewer standing in the gallery looking into the aviary, his meaning is immediately obvious. I become just as interested in the behaviour of visitors watching the birds, as in the birds themselves. The effect is even more pronounced in an installation called The Hunting Blinds, which surrounds the aviary. Each is based on a ‘hide’ or ‘blind’ used by hunters to watch animals in the wild, but each has a carefully elaborate interior that conjures the motivations of these different hunters. The lair of ‘The Glutton’ hosts a carefully laid table, the librarian’s a well-stocked bookshelf, chair and flask of hot drink. But, again, I am immediately struck by looking through and out of the blinds, for through the windows you see, not the hunter’s wild animal prey, but exhibition goers intent on their own object engagement.

Installation view of Hunting Blind (The Glutton) (detail) in ‘Mark Dion: Concerning Hunting’ at Kunstraum Dornbirn, Dornbirn, Austria, 2008 Courtesy Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna; photo: © Adolf Bereuter

Dion also makes the viewer think differently about each object. A pioneer of installation art, Dion drew inspiration from Surrealism and Modernism to engage in a thought-provoking way with the objects and institutions of natural history. His installations ask you to question what is a natural object, what is manmade, and how they should be looked at in an art gallery. In The Library for the Birds of London I become fascinated by how the zebra finches have concentrated themselves on a single high branch. Lined up, with their inquisitive faces staring down, they echo surrounding branches that have been carefully fashioned into shelves of books. The latter have been arranged by Dion, but the finches have arranged themselves in response to the gallery, visitors and objects.

Upstairs, the visitor becomes a character in one of Dion’s stage sets. The Naturalist’s Study is a space with furniture and books, where visitors can stop and read, playing the part of the naturalist. But it is also filled with objects and images, by Dion, which raises immediate questions about what it is you are studying. A (false) unicorn horn sits in a box, a series of carefully labelled photographs of polar bears on the wall are each actually of a different stuffed and displayed museum specimen. Even the wallpaper presents a specially designed menagerie of animals. As a visitor used to the displays of natural history museums, I am forced to question the categories of these objects and how I should understand them.

Bureau of the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and Its Legacy (2015), Mark Dion. Photo: Paul Cliff; courtesy Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester

Dion’s work often plays with such questions of taxonomy. Next door, Bureau of the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacy is not interactive. The visitor can only peer through the glass window into a study crammed with objects from stuffed animals to keys and wax teaching models. Partly you feel you are seeing inside the curator’s mind, and start to find unlikely connections between these disparate objects. Yet you are also forced to question the status of these items as ‘museum objects’ relegated to this study, closed off behind glass away from human interaction.

Adjacent to this, Tate Thames Dig reveals the simple power of opening a drawer or cupboard. Drawn again as much to other visitors as to the objects on display, I was fascinated by the expressions and exclamations of people as they tentatively opened a drawer to reveal a collection of ceramic shards excavated on the Thames foreshore near Tate Britain or of plastic bottle tops discovered near Tate Modern. The taxonomies of the drawers vary, with objects grouped sometimes by colour, sometimes by size, material or function. Thus, behind each wooden frontage is a group waiting to be decoded and explored.

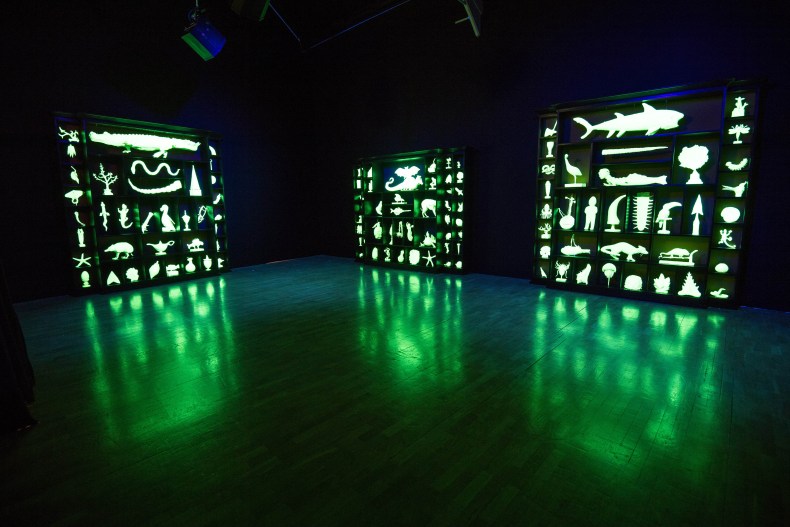

Installation view of The Wonder Workshop (2015) at ’Mark Dion: Theatre of the Natural World’ at Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2018. Photo: Jeff Spicer/PA Wire

The final installation, The Wonder Workshop, is the most striking. Entering a dark space you are presented with three display cases of strange plaster objects, illuminated by ultraviolet light so that they glow softly green. Each object embodies a complex history of production: they were produced in a project from 2015, in which Dion set up a Renaissance-style workshop in a Venetian palazzo which produced sculptures from 17th-century wunderkammer engravings. Now presented in this eerie, unsettling light they seem half alive, waiting for the visitor to activate them. A simple change of light and pace has worked wonders.

Dion’s emphasis on participation and immersion is no longer unusual in art or museums. Yet his works have lost none of their surprise and magic. Encountering the natural world in an art gallery, through the prism of Dion’s own careful engagement, is a surprisingly cerebral experience. Each piece requires the visitor to unpick its careful relationships, to act as natural historian and artist in tandem, behaving, as Dion sees it, like ‘detectives at a crime scene’, making sense of their environment through his accumulation and juxtaposition of rich material clues.

‘Mark Dion: Theatre of the Natural World’ is at Whitechapel Gallery until 13 May.