The collection of ancient glass at the Yale University Art Gallery has never been displayed as appealingly as it is in this small jewel of an exhibition. The rich, royal purple colour of the gallery, complemented by a gold band of pattern high on the wall, is inspired by the colour and design of one of the more noteworthy objects in the exhibition, a cylindrical cup dating to the 3rd or 4th century AD and bearing a gold-leaf inscription in Greek that also provides the show’s title.

The pieces in the exhibition, all drawn from the permanent collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, are attractively arranged in thematic groupings set atop a broad shelf that runs along the walls of the gallery. Rounding off the display are four freestanding cases in the centre of the room. Quotations from ancient writers, from Mesopotamian to Roman, provide a glimpse of how glass was made and used in the ancient world. My favourite is from the Satyricon of Petronius (section 50): ‘[Glass] doesn’t stink like bronze, and if it weren’t so breakable, I’d prefer it to gold. Besides, it’s cheap as cheap.’

While most visitors might disregard these quotations as present merely to provide ‘atmosphere’, they are, in fact, some of the few remaining written sources that refer to glassmaking in antiquity. Glass was not considered a luxury art in the ancient world although – since it was challenging both to make the material itself and then to shape it into functional objects – for the first 2,000 years of its existence it was a material reserved for the ruling classes.

Cup with a palmette band, bearing the inscription ‘Drink that you may live for ever’, 3rd–4th century AD, Roman, eastern Mediterranean, possibly Syrian. Yale University Art Gallery

We know the names of only a handful of glass artisans, compared to those of famous sculptors and painters; these survive because they were incorporated into the design of the moulds used to shape them. Yale is fortunate to have a mould-made cup by a 1st-century glassmaker named Ennion, arguably one of the finest glassmakers from antiquity who was known for the refined designs and elegant shapes of his works. (He was the subject of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Corning Museum of Glass in 2014–15.) Ennion’s wares, like much of Roman mould-blown glass, are paper thin and thus extremely lightweight. The modern equivalent would be drinking from the finest Lobmeyr wineglasses. The technique of mould-blowing allowed glassmakers like Ennion to create vessels that were the same shape and size, creating uniformity both in design and capacity – something we take for granted today when buying a set of wineglasses or a bottle of olive oil.

When museum visitors first encounter ancient glass, they are amazed to learn that manmade glass is such an old substance, and then are astonished that such fragile materials have survived for thousands of years. Most museum collections of ancient glass exist because many of the works were deposited in burials and survived in a protected environment. Yale’s collection, like so many others, was largely gifted to the institution from private collectors who acquired these works in the later 19th and first half of the 20th century, a time when archaeological contexts and modern provenances were less of a concern. But because Yale’s ancient art collection has an archaeological focus, important fragments from excavations are also on view to compare to complete objects, and to illustrate colours, shapes, and manufacturing techniques that don’t otherwise exist within the collection. These fragments serve to remind us of the value of context.

Fragments of a vessel (upper fragment inscribed ‘The[tis]’, 2nd-3rd century AD, Roman, Syrian, Dura-Europus. Yale University Art Gallery

![Fragments of a vessel (upper fragment inscribed 'The[tis]', 2nd-3rd century AD, Roman, Syrian, Dura-Europus, Yale University Art Gallery](http://new-dev.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/DRINKINGSOCIETIES-e1513792417153.jpg?resize=392%2C664)

Two fragments that are very important to glass scholars come from the excavations at Dura-Europos in central Syria; they were once part of a painted and gilded vessel and thus represent a type that rarely survives. While one of the fragments retains floral decoration, the other preserves the partial head of a woman wearing a diadem, and four letters of her name. She is Thetis, the mother of the Greek hero Achilles. It is tantalising to consider what a beautiful piece it must have been when made and used almost 2,000 years ago.

After marvelling at its age and fragility, the next question visitors usually pose about ancient glass is ‘How was it made?’ The exhibition’s curator, Sara E. Cole, who organised the show while a graduate student at Yale, has chosen to arrange the materials by their manufacturing technique, an approach that also roughly follows the chronological and geographic journey that glassmaking took from Mesopotamia and Egypt, and then west across the Mediterranean world in the 1st century AD. Small tablets displaying videos are adjacent to cases with technical focus. The videos, each of which shows a modern interpretation of an ancient glassmaking technique, have been provided by the Corning Museum of Glass and feature the skills of master glass-artist William Gudenrath. The techniques covered include cast and mosaic, free-blown, mould-blown, cut, and decorated free-blown and, with few exceptions, these methods developed for shaping glass in antiquity are still in use by glassmakers today.

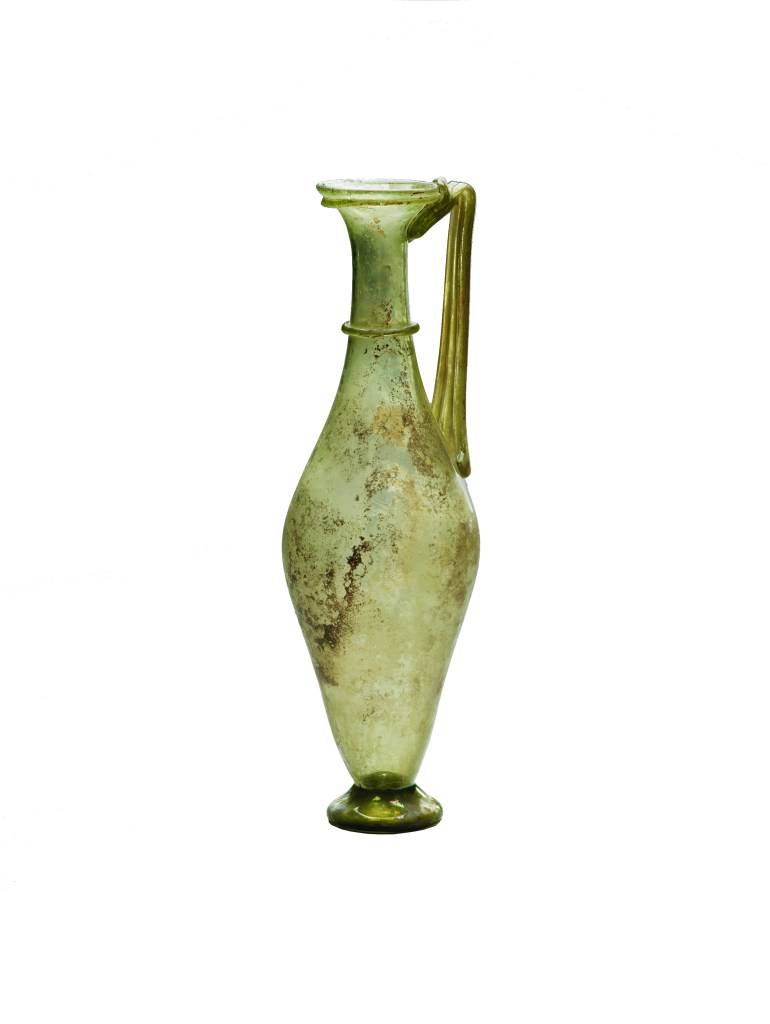

There are cases focusing on the function of glass objects in the ancient world. These note the role of glass in trade and commerce, and highlight the number of works related to drinking and dining in Yale’s collection (the latter are complemented with reproductions of Roman frescoes depicting glass vessels in use, another primary source of information for ancient glass). A tall elegant pitcher, used no doubt to pour wine, would feel right at home in today’s dining room.

Pitcher, 3rd-4th century AD, Roman, eastern Mediterranean. Yale University Art Gallery

The themes of making and function ably suit the needs of an exhibition that is seen by students and general visitors. But it is the rich diversity of Yale’s objects and their aesthetic appeal that make this show a visual treat. Additional works made of faience and terracotta are included in the two cases of Egyptian cast and Greek core-formed pieces. They serve as a reminder that glass vessels and objects (beads and inlays) existed side-by-side with works made of other materials. The unique properties of glass did not make it a ‘breakout’ material until the development of glassblowing in the mid 1st century BC. This change in approach to the design of glass in the 1st century can truly be appreciated in a single-room show such as Yale’s, where one can see the range of shapes and decoration at a glance.

The Yale University Art Gallery has a long history of mounting exhibitions conceived and shaped by their talented students, and is fortunate to have endowed funds to assist with their realisation. Such is the case with ‘Drink That You May Live’. After the exhibition closes, some of the glass collection will be installed in a main floor gallery with other archaeological material. Given its beauty and rarity, this is welcome news.

‘Drink That You May Live’: Ancient Glass from the Yale University Art Gallery ran from 4 August–12 November.

From the November 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.