This article was published in the November 2020 issue of Apollo. Museums and galleries in the UK are closed from 5 November due to Covid-19; visitors are advised to check venue websites for further updates.

It is hard not to smile on first stepping inside the Box, an ambitious civic museum that opened in Plymouth, South Devon, in late September. For a start, it is quite simply gladdening, in a year in which all UK museums have been forced to close, to walk through the doors of a shiny new cultural institution – and one that, following investment of more than £40m, is a reminder of more optimistic times. But the pleasure is also visual. Overhead, flanking the reception area like cartoonish household gods, hangs an armada of 19th-century naval figureheads, most of them painted colourfully following an extensive conservation campaign. For a moment, I feel as though I’ve stumbled on to the set of a particularly jaunty production of H.M.S. Pinafore.

A collection of 19th-century naval figureheads, installed in the entrance hall at the Box, Plymouth. Photo: Wayne Perry

This bright foyer is part of a new building by the architecture firm Atkins, which has pulled together the Edwardian City Museum and Art Gallery and the post-war Central Library into a single cultural complex bordering a sloping square, opposite what was once the parish church of St Luke’s and is now a space that will be dedicated to contemporary art installations. That the figureheads seem to deny their bulk, held aloft by just a few cables, in a sense reiterates what is, from the exterior, the top-heavy nature of the museum’s design: a vast, mirror-clad structure caps it, jutting out from the glass facade like the discarded shoebox of a giant.

This box, which gives the museum its name, provides storage for more than two million items in its collection – not only from the old museum, but from other regional collections such as the Plymouth and West Devon Record Office and the South West Film and Television Archive. (The Box is also now home to the Cottonian Collection, a remarkable holding of prints, drawings and rare books that was passed between generations of antiquarians before its donation to the city in the mid 19th century.) If the structure is visually cumbersome, it nevertheless makes an intriguing symbolic gesture. It has become commonplace to talk of how the lion’s share of museum collections languishes in basements; to hoist one into the air, above galleries and other public spaces, is a reminder of how any museum’s activities take place under the aegis – and, yes, sometimes the burden – of its permanent collection.

Tobacco jar by the Martin Brothers (19th century). The Box, Plymouth. Photo: © Plymouth City Council, the Box

The breadth of the Plymouth collections becomes apparent in permanent galleries that explore the artistic, historical and natural-historical legacy of the city and region. The wit and theatre of the foyer carry over here. A replica of one of Devon’s prehistoric inhabitants, a woolly mammoth, presides over the natural history gallery. In the double-height art gallery, highlights from the decorative-arts collection are shown dramatically in a floor-to-frieze cabinet that stretches across an entire wall (ceramics are particularly well represented: it was a Devonian Quaker minister, William Cookworthy, who manufactured the first hard-paste porcelain in Britain).

A Fish Sale on a Cornish Beach (1885), Stanhope Alexander Forbes. Photo: © Plymouth City Council, The Box

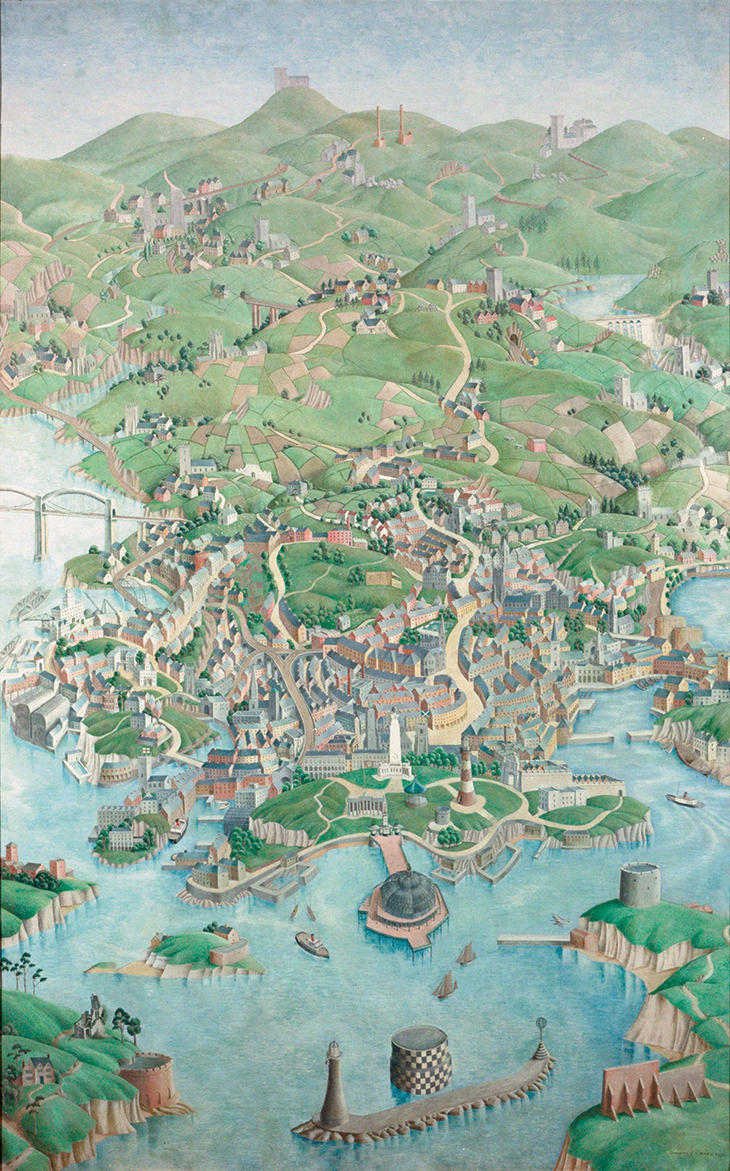

The paintings on display include old favourites such as Stanhope Forbes’s A Fish Sale on a Cornish Beach (1885), as well as works by local boy Joshua Reynolds. But there are also surprises. A section given over to views of Plymouth opens with Dorothy Ward’s An Aerial View of Plymouth and Environs (1933), an Arcadian vision of the city before the war, somehow made strange by its tall portrait format. Stanley Spencer’s Hoe Garden Nursery (1955) allows only a glimpse of Plymouth Hoe, scene of so much local commemoration and pageantry, behind a more provisional world of sheds and potting beds.

An Aerial View of Plymouth and Environs (1933), Dorothy Ward. The Box, Plymouth. Photo: James Bannister; © Plymouth City Council, the Box, and artist

That the ocean and the artefacts, traces and complex legacy of ocean-faring should take centre stage at the Box is hardly surprising. The ships that have sailed from Plymouth make for a roster that has long been a marker of civic pride but which has more recently been the focus of scrutiny: the Golden Hind, the Mayflower, HMS Endeavour, HMS Beagle. The dockyards at Devonport were the chief target of the bombing raids which razed the city during the Second World War, killing almost 1,200 of its citizens and entailing its post-war reconstruction (oft scorned, but increasingly the subject of reappraisal and preservation campaigns). HMNB Devonport is still the largest naval base in Western Europe.

All this is explored extensively at the Box. On the ground floor, a ‘Port of Plymouth’ gallery gives on to ‘100 Journeys’, moving from the city’s historical infrastructure, and the population it supported, to the global order it helped to occasion. There is a strong sense here of, on the one hand, the residual prestige of the stories that the city has told about itself and, on the other, the prospect of rephrasing those stories in the future. The Drake Cup, for instance, which – tradition has it – was presented to Drake by Elizabeth I after his circumnagivation, is displayed in a case that draws attention to Drake’s role in early Transatlantic slave voyages, but also records how the object was presented to the city in 1942 as an emblem of its determination during the Blitz. Local and global narratives interject one another, asking visitors to hear both.

The Drake Cup (1571–95), Abraham Gesner. Photo: © Plymouth City Council, The Box

That the Box is a place for such conversations is evident throughout the building. Its major opening exhibition, ‘Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy’, has been co-curated with the Wampanoag Advisory Committee to the quatercentenary programme; it presents Native American perspectives on English colonisation alongside a look at how the Mayflower’s voyage has exerted such a hold on British and American cultural imaginations (until 18 September 2021). Elsewhere, in the ‘Active Archives’ gallery, artefacts from the Second World War and its aftermath consort with hundreds of volumes on the history of Plymouth, which visitors are free to browse (there are ample cushioned benches).

The fused glass window designed by Leonor Antunes and installed in St Luke’s Church, the Box, Plymouth. Courtesy the Box and the artist

In St Luke’s Church, the inaugural installation also dwells on local heritage, but finds a way to present it afresh. The Portuguese artist Leonor Antunes has suspended a forest of rope, leather and brass sculptures from the ceiling, a contemporary take on Plymouth’s historical ropemaking tradition. Antunes has also designed a fused glass window for this space, which takes as its cue the marbled end papers of an 18th-century book on entomology by Maria Sibylla Merian, an original copy of which is housed in the Cottonian Collection across the square. Throughout the Box, it feels like the conversation is just getting started.

From the November 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.