In Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Jane Bennett describes cultivating ‘the ability to discern nonhuman vitality’ as an explicitly ethical task. It is interesting, then, to consider ‘Slow Objects’, the current exhibition at the Common Guild, as a point in the ethical trajectories of the three artists included: Vanessa Billy, Edith Dekyndt and Erin Shirreff. What happens when attention is slowed down and turned towards the object? In this exhibition, object ethics becomes a leveller, refusing to prioritise value, fixity and fame over the mundane, mutable and domestic.

Installation view of ‘Slow Objects’ at the Common Guild, Glasgow, showing Vanessa Billy’s Old Cloud (2017) and Erin Shirreff’s Relief (no 3) (2015). Shirreff work: Perimeter, London

Slow objects of all kinds fill both galleries, the hallway and the stairwell. In such a show it becomes impossible to ignore the former domesticity of the Common Guild itself – a Victorian townhouse with its fireplace, cornicing and wrought-iron balusters intact. The artworks have been finely tuned to these original features, so that the half-moon shapes of Shirreff’s print Relief (no.3) (2015) mirror those of the fireplace opposite, and shrivel into the broken fusiform halves of Billy’s Refresh, Refresh (Mould Squeeze) (2016). These are overlooked by Dekyndt’s austere, dirty-hemmed wall hanging Underground 05 (Tournai) (2017), an upright oblong that speaks to the facing window. Such works actively encourage this alternating view from object to context, playfully undermining their own privileged status within the gallery.

Installation view of ‘Slow Objects’ at the Common Guild, Glasgow, showing Vanessa Billy’s Old Cloud (2017) and Edith Dekyndt’s Slow Object 01 (1997)

The awkward, in-between spaces are well occupied by Dekyndt’s film and sculptural work. At the top of the staircase to the lower ground floor, a mesmeric film simply titled Slow Object 01 (1997) shows a dustsheet-covered fireplace ‘breathing’ as air from the chimney sucks the material in and out. Further up, the pristine white stairs are tainted by the chemical, Fairy Liquid-like seepage of Deodant (2015), trickling from the corner of an otherwise nondescript wall piece.

Deodant conjures deodand: an object responsible for accidental human death under old English Law. These objects would be sold on to the crown to compensate for the harm caused, and are, as Bennett notes, ‘suspended between human and thing’, evidence of how humans collaborate with objects to populate realms of law, property and culture.

It’s refreshing, then, to encounter Erin Shirreff’s pseudo-minimalist works probing the afterlives of famous sculptures. Once these totemic, ‘seemingly authorless’ artworks become enshrined and recognisable as images, how do we encounter them in physical space? In the film Sculpture Park (Tony Smith) (2006), maquettes of Smith’s work are set in a model park in Shirreff’s studio, and subjected to an ersatz snowstorm. The grainy black and white footage belies this artifice, and fits seamlessly into the monochrome, monolithic tradition it gently undermines.

Installation view of ‘Slow Objects’ at the Common Guild, Glasgow, showing Erin Shirreff’s Signatures (1) (2011), Edith Dekyndt’s Slow Object 02 (1997/2016), and Vanessa Billy’s Les fonds qui plerent (2017). Erin Shirreff work: David Roberts, London

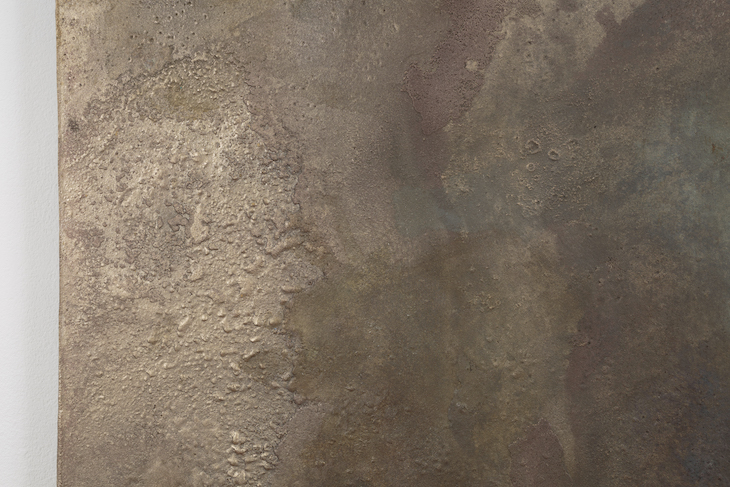

Vanessa Billy’s works engage in a less subtle dialogue with the Common Guild’s interior; the bright bio-resin splashes of Les fonds qui pleurent (2017) are a welcome punctuation to the subdued tones elsewhere, and, crucially, foreground the alchemy of material processes, as in the patinated bronze of Old Cloud (2017).

Old Cloud (detail; 2017), Vanessa Billy

The human actors involved in ‘Slow Objects’ – artists, curators and the gallery team – have successfully co-authored a contemplative poetics of space, but, in essence, it is the nonhuman ‘authors’ of environment, reaction and process whose voices are amplified. Such material utterances may appear slow and understated, but they figure broader, ethical questions of environmental responsibility: do we have time to notice and attend to the nonhuman? Time spent with ‘Slow Objects’ might be one way to practice.

‘Slow Objects – Vanessa Billy, Edith Dekyndt and Erin Shirreff’ is at the Common Guild, Glasgow, until 17 December.