Immediately after the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks took over the Imperial Porcelain Factory on the outskirts of Petrograd (today Saint Petersburg), renaming it the State Porcelain Factory. (In 1925, it was renamed the Leningrad Lomonosov Porcelain Factory after the great 18th-century scientist Mikhail Lomonosov.) Founded in 1744, it was the third of the European hard-paste porcelain factories after Meissen and Vienna and worked exclusively for the Imperial court to which it supplied dinner services for palaces and yachts and presentation pieces such as huge vases and figurines. At the outbreak of the First World War many of the factory’s workers became soldiers, leaving behind only a skeleton labour force. The remaining workers made plain plates and electrical fittings for the military hospitals.

The large inventory of glazed but unpainted white hard-paste porcelain platters, plates, cups and saucers found at the factory in 1917 was to be transformed into message-bearers for the Revolution. This inventory bore the ciphers of any of the last three czars. In the first few years after the Revolution when these items were decorated for propaganda purposes, the ciphers were covered with a patch of green or black paint, and the State Porcelain Factory (SPF) mark of hammer, sickle and cog – designed by Alexey Karev – and the year were painted alongside. After 1921, the Imperial cipher was often left uncovered.

Anatoly Lunacharsky, commissar for education and the arts, understood the useful role the factory could play in the Soviet leaders’ propaganda campaign within Russia and abroad. He arranged for it to be placed under the authority of his ministry, known by the acronym of Narkompros. Lunacharsky was a member of the Bolshevik inner circle who had access to Lenin, and a cultivated man who had travelled widely. He had been the arts correspondent of a Russian magazine in Paris before the First World War, understood art and artists, and was able to defend artistic projects and protect artists.

The new government needed to publicise its politics and to win the minds and the hearts of people throughout Russia’s vast territory. To do this in pre-radio and pre-television times in a country engaged in a world war and a revolution and on the brink of a civil war was no easy matter. It initiated a propaganda campaign using political posters and illustrated news bulletins placed in street-level store and office windows. It covered trains, trucks, and river boats with brightly painted pictures and slogans. These were sent to the war fronts, and toured the country with trained agitators on board and gramophones with which to broadcast Lenin’s speeches. Artists were urged to leave their bourgeois studio work and participate in the designing of street pageants and the decoration of entire squares; the façades of buildings became their canvases. The images and slogans that appeared on the trains, boats and newly erected monuments could also be seen at a smaller scale: on propaganda porcelain.

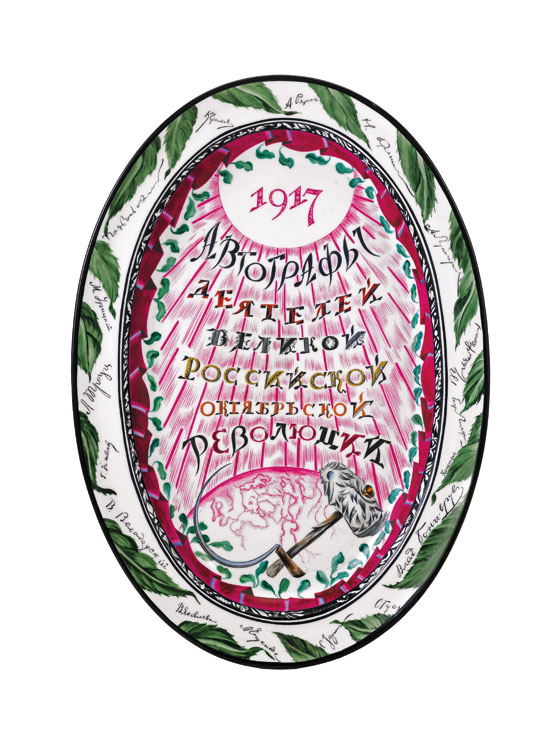

Signature Platter (1918), Sergei Chekhonin. Image courtesy the author

Revolutionary porcelain was painted by a group of talented artists under the guidance of Sergei Chekhonin, who was a well-known graphic artist, illustrator, watercolourist, and a major decorator of ceramics before the Revolution. It was for all these reasons that Narkompros appointed Chekhonin as the first artistic director of the SPF, where he remained until 1928 (except for the period in 1923–24 when he was director of the Volkhov Factory near Novgorod). Many famous as well as unknown artists worked for the SPF, regardlness of their political convictions, as working at the factory meant assured bread rations during the terrible civil-war years (1918–21). Chekhonin was the creator of the school of propaganda porcelain, known as agitfarfor (agitational porcelain) in Russian, which combined imaginatively designed revolutionary and political subjects with elegantly worked symbols, slogans and superb calligraphy, as well as colourful designs of Russian folklore, with flowers, fruit, foliage, and lots of cisele gilding.

The artists worked in many different styles, from neoclassicism, to cubism and Suprematism. However, all porcelain decorated at the SPF in the decade after the Revolution, even when free of slogans, or abstract in design, was meant for propaganda purposes. In the 1920s the Soviet government, desperate for foreign currency, sent hundreds of pieces abroad to exhibitions and trade fairs. Thanks to this, certain propaganda pieces which were later destroyed in the USSR during the Stalinist era have survived in foreign collections. Some of these pieces reflect the importance and activities of men such as Leon Trotsky and Grigori Zinoviev during the first years after the Revolution, whereas Stalin does not appear on any early propaganda porcelain.

A superb example of how porcelain can bear witness to the Revolution is the huge platter known as the ‘Signature Platter’ (1918), designed by Chekhonin. The centre part is covered with elegantly designed, multicoloured Cyrillic letters that read: ‘Autographs of the Architects of the Great Russian October Revolution.’ The lower part of the cavetto is decorated with a hammer and sickle on either side of a section of the globe representing Russia. A twirling red ribbon and oak leaves (traditionally associated with heroes) circle the cavetto. There are 17 facsimile signatures of well-known revolutionaries excluding that of Stalin who, though at the time a member of the recently founded Politburo, was still considered unimportant. (It is a pity that this platter was not included in the Royal Academy’s current exhibition ‘Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932’ among the portraits glorifying Stalin.) The ‘Signature Platter’ was brought back to England by Captain Desmond Allhusen who was assistant British agent in Moscow in the early 1920s. In 1923, Allhusen visited the State Porcelain Factory’s shop in Moscow with the British agent Sir Robert Hodgson, and purchased the object. Several copies were made but no such platter survived in Russia.

The Mind Cannot Tolerate Slavery plate (1918), Sergei Chekhonin. Image courtesy the author

From October 1917 to the spring of 1921, the Bolsheviks struggled desperately to maintain power as the civil war raged throughout Russia. Their survival depended in large part upon the Red Army created by Trotsky; many plates and cups celebrating the Red Army and honouring its creator Trotsky were painted at the porcelain factory. The cobalt-blue border of Mikhail Adamovich’s ‘Hail to the Red Army’ plate is decorated with oak leaves for valour. Within the cavetto there is a portrait of Trotsky, a red star with crossed hammer and sickle, a facsimile of Trotsky’s signature, and a worker and a Red Army soldier holding a sign that reads ‘1917 Red Army 1922’. They also hold a golden wheel with the numeral ‘5’ in the centre and ‘23 October, Moscow 1917’. Underneath in iron-red script are the words ‘Defence of the Workers’.

During the first few years of Communism plates were often painted with the same slogans and aphorisms that were appearing in the newspapers and posters. Class struggle and the new revolutionary morality were important themes; another was the conflict between old and new. Extracts from speeches by Lenin provided a source of inspiration, as did quotations from socio-Utopian writers, revolutionary activists of many nationalities, and the Communist Manifesto. Texts were also taken from classical authors such as Ovid and Cicero, from Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, and even from the Gospels. The range of source material was paralleled by an equally wide range of treatments; each artist had favourite motifs and a characteristic manner of execution.

He Who Does Not Work Does Not Eat plate (1921), Mikhail Adamovich. Image courtesy the author

In 1918 Chekhonin decorated a series of plates with slogans: ‘He who is not with us is against us’; ‘Struggle gives birth to heroes’; ‘The mind cannot tolerate slavery’; and ‘Science must serve the people’. The cautionary maxim ‘He who does not work does not eat’ is the message of a plate designed by Adamovich. This is an adaptation of St. Paul’s Second Epistle to the Thessalonians, chapter 3, verse 10: ‘if any will not work, neither let him eat’. It was incorporated into the Constitution of the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic) in 1918. Here it dances around the border in multicoloured letters, framing a composition that includes a portrait of Lenin (adapted from a famous portrait drawn from life by Nathan Altman), some ration cards, half an Imperial eagle and a red star. In the prototype of this plate created in 1921, the red star of the Revolution is on top of the eagle, crushing and obliterating it. However, when copies of the plate were ordered in later years, the factory artists were unfamiliar with the symbols and thought it a pity to cover up the eagle, so they painted the star alongside or underneath. One often finds such anomalies in agitfarfor.

Soviet heraldry acquired great importance in the decoration of propaganda porcelain. An elegantly executed hammer and sickle on their own or entwined with flowers and foliage, or the initials RSFSR, elegantly calligraphed, are often the only design elements in plates. A surprising amount of gold was used on propaganda porcelain. But, as the Soviet art historian Lydia Andreeva explains, although gold was associated with the luxurious past of the Imperial regime it nevertheless seemed appropriate for the emblems and monogram of the new republic. A plate by Rudolf Vilde celebrates the second anniversary of the October Revolution. It contains the emblem of the new republic and a fluttering red banner with the slogan ‘Victory to the Workers – 25 Oct.’ Above the banner are the dates ‘1917–1919’. The elegant cobalt-blue border is decorated with leaves, flowers and working tools, beautifully painted in cisele gold and oxidised silver.

Victory to the Workers – 25 Oct plate (1918), Rudolf Vilde. Image courtesy the author

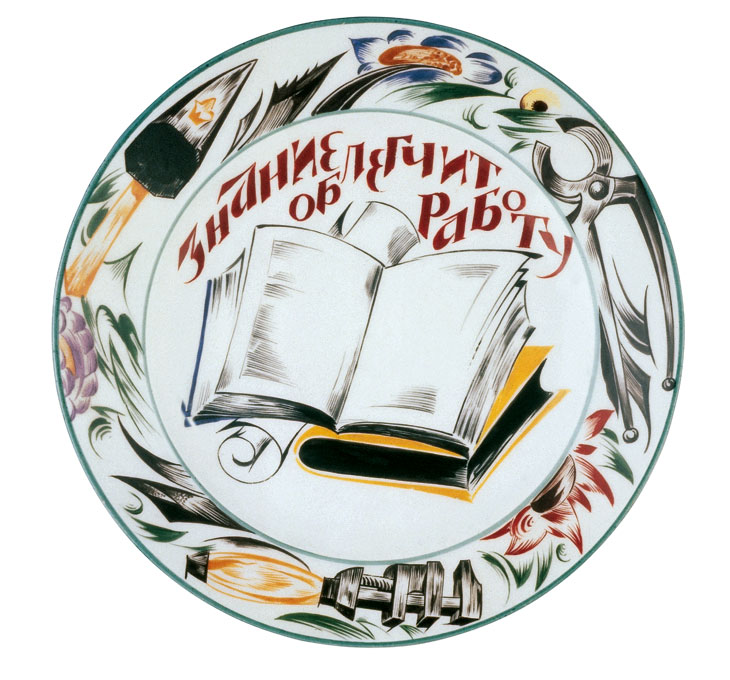

Also by Vilde is a plate showing tools and a book, which is known as the ‘Knowledge Lightens Work’ plate due to the slogan in Cyrillic letters in its cavetto. The large black part of the trowel covers a heraldic sign. One sees this quite often in propaganda porcelain painted on plates that had been made earlier. The slogan was popular and numerous copies of the plate exist. Also popular were the First of May plates and small dishes celebrating the workers’ holiday, which had been forbidden under the czars. These were usually decorated with a multicoloured bouquet of flowers incorporating a hammer and pliers, the whole entwined by a red ribbon.

Because the factory could not be reached by public transport which, in any case, had become almost non-existent, Chekhonin decided to relocate the artistic workroom in the centre of Petrograd. He found the ideal workshop in the building that, before the Revolution, had been the Baron A. Stieglitz School of Technical Design. Between 1918 and 1920 all design and original painting work took place here, but copying continued to be done at the factory itself. The artists worked at two long tables in a room that was often freezing – there was not always wood for the Franklin stove, which, even when burning, could not heat the vast room properly. The artists frequently had to work with their coats and fingerless mittens on. They later remembered it as an exciting and exhilarating time, despite the food and fuel shortages, and managed to express some of this excitement in their work. They were aware that they were part of an important propaganda campaign with lofty ideals and that their art had a valued place in Soviet life. And during the first three years of the SPF they were allowed a fairly free hand in what they designed.

Knowledge Lightens Work plate (1921), Rudolf Vilde. Image courtesy the author

The terrible suffering of the Russian people in the famine and the typhus epidemic of 1919–21, which claimed millions of lives, provided tragic subject matter for the porcelain artists. A series of plates and dishes were made for a special sale to raise money for the starving population of the Volga region. These items were marked on the reverse with a special gold mark designed by Chekhonin and painted by hand. Vilde painted the most striking of the famine plates in which a worker holding a sledgehammer and a rifle attacks a gloating figure of death – the Great Reaper – who holds a scythe and carries a sheaf of golden wheat. Golden Cyrillic letters circling the border read: ‘In Aid of the Famine-stricken Population of the Volga Region’. Chekhonin painted perhaps the most poignant of all the famine sale dishes, a grieving mother/Madonna figure holding two starving, wailing children. All three have pale green, skull-like faces.

After the October Revolution, the State Porcelain Factory also began producing sculptures, which reflected the new reality instead of the aristocratic ladies and gentlemen in 18th- and 19th-century dress. The first in 1918 was a bust of Karl Marx, produced in two sizes. Then came a statuette known as ‘The Red Guard’. Both were designed by Vasili Kuznetsov. However, it was Natalya Danko who became the acknowledged chronicler of the characters of the new Soviet era. She had received thorough training in sculpture under Kuznetsov. When he decided to leave Petrograd in 1919, Danko became head of the sculpture workshop until the factory was evacuated during the Second World War.

Great Reaper plate (1922), Rudolf Vilde. plate (1922), Rudolf Vilde. Image courtesy the author

Basing her work on the old Russian tradition of genre figurines, Danko created statuettes with contemporary relevance. Her subjects were the people in the street and everyday life: men, women and children, soldiers and sailors of the Revolution, bureaucrats, gypsy fortune-tellers, partisans, a little newspaper boy, a militia woman, a woman sewing a banner, actors, ballet dancers, and the poet Anna Akhmatova. Danko worked for 313 months at the porcelain factory creating 311 different works. One of her most notable figurines comprises two Soviet stevedores unloading sacks of American meal. One sack is stamped: ‘AMEPICAIN MEAL USA’ (in Russian P = R hence the misspelling. The ‘I’ is simply an error). The other is stamped in Cyrillic letters, ‘GOSTORG PETROGRAD RSFSR’ (Gostorg stands for State Trading Agency). The prototype of the figurine was created in 1922 and quite a few were produced. It is proof in porcelain and a surviving Soviet reminder of the generosity of the United States and the American Relief Administration (ARA) which saved hundreds of thousands of lives at the time of the famine. After Stalin came to power all Soviet citizens who had worked for ARA were arrested as spies and shot or deported. Examples of the figurine survived abroad.

In striking contrast to the representational, often didactic, character of agitprop porcelain, the aim of the Suprematists was to build ideal abstract forms based on the principles of geometry. Yet these works are usually grouped with agitprop porcelain since the two styles are contemporaneous. The Suprematists Kazimir Malevich, Nikolai Suetin and Ilya Chashnik worked at the factory for a few years when they arrived from Vitebsk in 1922 – they needed a worker’s card which provided bread. Suprematists considered the colour white – and therefore white porcelain – an ideal base because it expressed weightlessness and infinity. Their ideas were original and thought-provoking but not very practical, nor liked by the masses. Only a few Suprematist pieces were created. The prototypes were kept at the factory storerooms, and a few hundred copies were made for export to trade fairs abroad where they were more popular than in Russia. Few original Suprematist pieces remained in Russia. In the past 20 years many repeats have been made.

Plate with Suprematist design (1923), Kazimir Malevich. Image courtesy the author

Due to its high cost and its scarcity, propaganda porcelain seldom entered the homes of the masses, nor did it help spread the ideas of the Revolution. Today, propaganda porcelain is collected by museums and private individuals in Australia, Europe, Russia, and the USA, and fakes abound. Nevertheless, it has always commanded attention with its vibrant colours and bold designs. It sometimes repels and often attracts, but rarely leaves the viewer indifferent, thus fulfilling the intentions of its creators.

From the April 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Suprematist teapot (1923), Kazimir Malevich. Image courtesy the author