From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

With interest in Old Masters and traditional art growing, spurred on by the blockbuster Vermeer exhibition in Amsterdam as well as the recent multi-million dollar auctions in New York of masterpieces amassed by Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen, the time could not be more ripe for TEFAF’s return to Manhattan in May. TEFAF is known for the deep well of art history its exhibitors draw from, and the American edition brings a fresher perspective, leaning more toward modern and contemporary art. Dealers in the field seem to agree, however, that it is not enough merely to present beautiful objects with a pedigreed history: making new discoveries and telling forgotten stories are important. TEFAF New York offers many of these this year, particularly by women artists and designers.

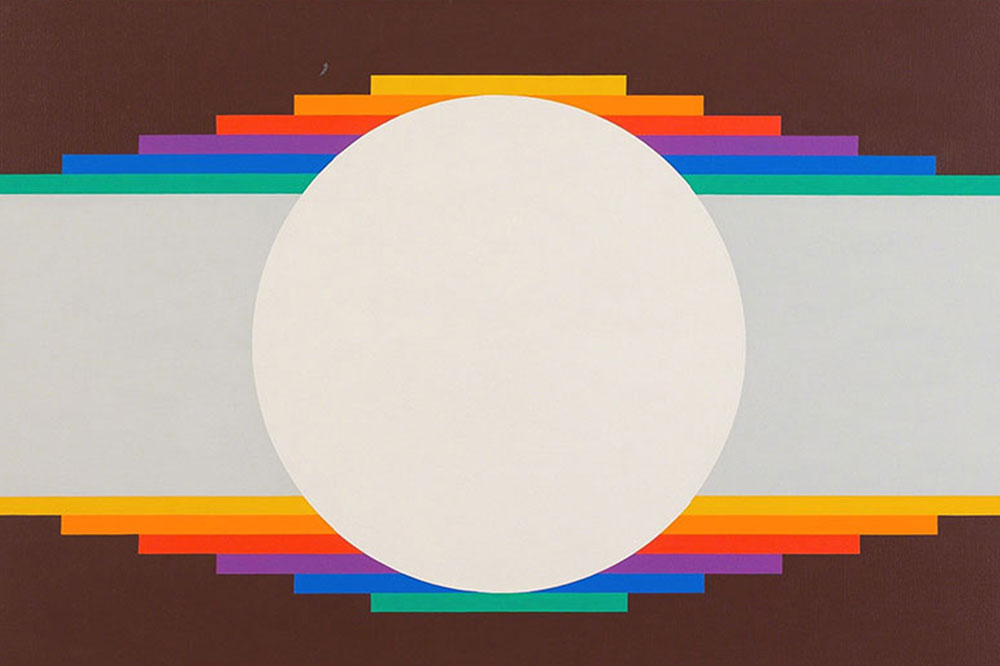

London’s Mayor Gallery, for example, is showing work by the Swiss painter and graphic designer Verena Loewensberg, a founding member of the Zurich Concretists and the only woman in the group, which included her close friend Max Bill. After studying weaving, design and colour theory at the Gewerbeschule in Basel in the later 1920s, as well as modern dance, Loewensberg turned to painting in the 1940s, following her own path to experiment with colour and geometric forms. ‘I have no theory, I am dependent on things that occur to me,’ Loewensberg said.

Erika Giovanna Klien was another pioneering woman artist, a leading figure of the Viennese Kineticism group, which had been founded by Franz Cizek, her drawing teacher at the School of Applied Arts. Influenced by theatre, dance and music, Kineticism and Klien’s work especially are marked by a sense of rhythm and movement, as seen on the stand of Viennese gallery Wienerroither & Kohlbacher. After visiting New York for an exhibition of her work at the Brooklyn Museum in the 1920s, Klien emigrated to the United States and supported herself as an art teacher at several city academies, including the Dalton School and the New School for Social Research.

Untitled (1965), Shirley Jaffe. Galerie Nathalie Obadia ($280,000–$330,000). Courtesy the Estate Shirley Jaffe and Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris, Brussels.

Taking the reverse route, New Jersey-born painter Shirley Jaffe studied at the Cooper Union in New York and the Phillips Art School in Washington, D.C., before moving to Paris in 1949. She would continue to live and work in the French capital, in a fifth-floor walk-up studio in the 5th arrondissement, until her death in 2016, at the age of 92. Part of the second generation of Abstract Expressionist artists, Jaffe was introduced to the movement by her friends Joan Mitchell, Sam Francis, Jean-Paul Riopelle and Al Held, but found more freedom working in the less hierarchical art world of Europe.

A residency in Berlin funded by the Ford Foundation opened up her work even further, allowing her to develop a unique, boldly geo- metric style, which can be found in the works shown by Galerie Nathalie Obadia, based in Paris and Brussels. Jaffe has been cited as an influence by younger painters such as Jessica Stockholder, Amy Sillman and Charline von Heyl, and a travelling exhibition that opened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris last year is bringing her work to wider attention, with stops at the Kunstmuseum Basel and the Musée Matisse in Nice this year.

Modern painters such as Picasso and Gauguin are known to have drawn on the work of Indigenous artists in their art, but borrowing from the opposite direction also occurred. New York’s Donald Ellis Gallery is showing a pair of wooden lion statues, likely carved around 1840 by an anonymous Haida artist. According to the gallery, North-west Coast artisans were sometimes commissioned to create certain objects, and the artist who created these more friendly than fierce felines was probably working from a photograph or published illustration – perhaps a museum catalogue given the objects’ resemblance to ancient carvings found across the Mesopotamian. ‘The nose, whiskers, and mane are fairly naturalistic, while the stylisation of the eyes, eyebrows, and mouth most identify the North-west Coast origin,’ the gallery says. ‘They present a somewhat startling and engagingly benign personification of a powerful carnivore.’

One half of a pair of lions (c. 1840). Donald Ellis Gallery (price on application). Courtesy Donald Ellis Gallery

On the more contemporary side, the French-Swedish designer Ingrid Donat is known for marking her hefty yet delicate bronze furniture with patterns drawn from the tribal scarification and decorative elements she saw on her childhood home of Réunion, a French island territory in the Indian Ocean. After studying at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Donat started work- ing in sculpture under the tutelage of Sylva Bernt, but turned to designing furniture in the 1980s on the advice of her friend Diego Giacometti. Unlike her usual darkly patinated pieces, the Table Basse Koumba coffee table with Carpenters Workshop Gallery (co- founded by Donat’s son, Julien Lombrail) is a bright, light bronze, with a thin shelf made from parchment suspended underneath the richly hammered top.

One surefire crowd favourite at the fair is Jorge Pardo’s crimson-lit bar, which served as the beating heart of the Mountain School of the Arts in Chinatown in Los Angeles. From 2009 until the bar closed in 2012, the space hosted lectures, performances and film screenings by artists and curators including Dan Graham, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Hans Ulrich Obrist – and served up delicious vanilla sake martinis. The bar has now been recreated as an untitled installation, brought to the East Coast by New York’s Petzel Gallery, ready for one lucky collector to belly up to a piece of West Coast art history at home.

TEFAF New York is at the Park Avenue Armory, New York, from 12–16 May.

From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.