In what has come to be considered by many as the era of the woman, the art world has just lost one of our most powerful matriarchs, Susan Rothenberg. The era began without her noticing. She understood the political complexities of gender, but she was too busy in her head and in her painting. ‘I think hard work makes art, not gender. I think art gets to a more guttural level,’ she told me years ago.

Few artists work harder than Susan Rothenberg did. A single mother for much of her early career, she painted in split shifts – during the day when her daughter Maggie was at school, and at night. For her, painting was the holy grail of image-making. However, like other painters of her generation in New York – Neil Jenney, Elizabeth Murray, Robert Moskowitz, Jennifer Bartlett – she was searching for a way to release it from the ethereal fog of Colour Field painting and the obdurate, static condition of minimalism.

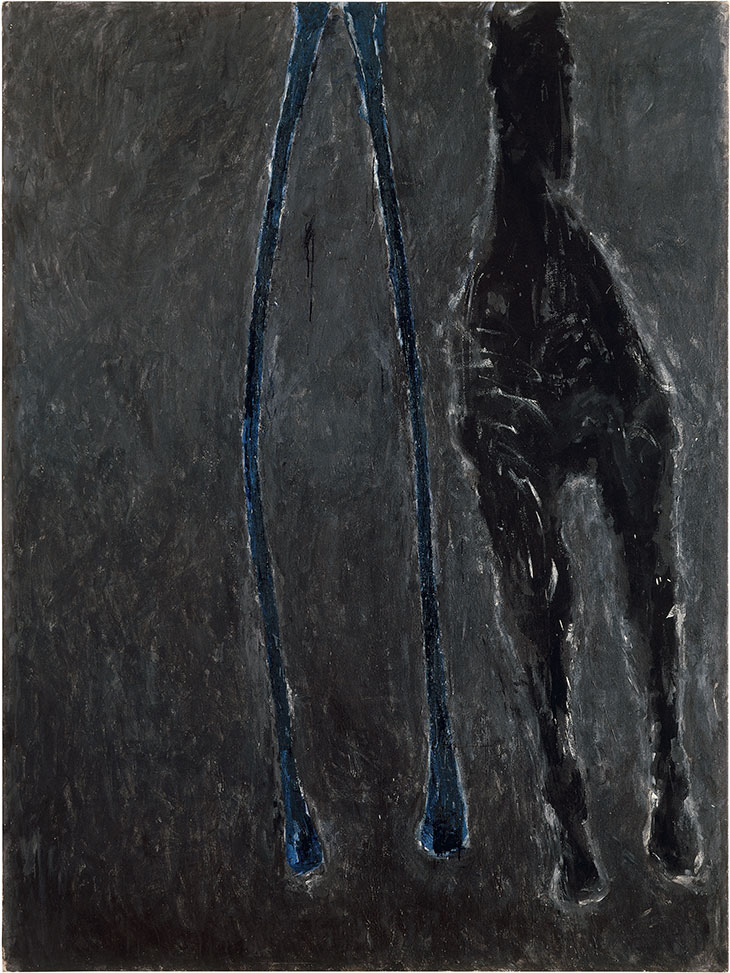

Wishbone (1979), Susan Rothenberg. Anderson Collection at Stanford University. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York; © 2020 Susan Rothenberg/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

When her first, massive horse paintings emerged in 1975, exhibited at the alternative SoHo gallery 112 Greene Street, she had clearly hit on something that resonated. Today, they hang in museums, as representative of a moment when abstraction would be forced to finally make room for new forms and identities, including those of women. And as it turns out, it was important that those horses were painted by a small, psychologically tough woman who recognised that this motif was a vehicle towards something deeper, and would soon be expendable. Many of her colleagues, mostly male, would have ridden those horses to the end of their careers, cashing in on a recognisable brand. Rothenberg later acknowledged, ‘One thing that I do think is a difference between men and women is that women generally go places that are deeper and messier than men, who generally want to make things coherent and iconic.’

Numerous writers, including myself, have explained Rothenberg’s horses stylistically, a painterly bridge between her minimalist elders and the new figuration her work would inspire in the late 1970s and ’80s. But Rothenberg’s work was never about style. If they are anything in the vicinity of style, they are powerfully expressionist. When I think about Rothenberg’s work now, I think of emotion. Even the horses have their human side, sometimes messy and even awkward. They run and jump and fall down. If you look closely, some drool and cry. One wears a bathrobe. We are drawn to these beings not only for their powerful grace, but also for their flaws. Some of the horses are turned from a profile image to a frontal one, exposing dark, human-like spectres moving toward us.

Blue Head (1980–81), Susan Rothenberg. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York; © 2020 Susan Rothenberg/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

The horses were a launching point for Rothenberg’s singular body of psychological figuration, unlike anything else we had experienced at the time, or perhaps since. She eventually tore the horse apart and reformed it into bones, arms, human heads and mask-like faces that had the feeling of ominous emotional signifiers. All art is biographical to some degree, but in those days, Rothenberg’s was mysteriously but brazenly so. In the late ’70s, with the horses in the rear-view mirror, and in the midst of a divorce, Rothenberg produced a series of stark heads outlined in paint: a gusher of black liquid spews from the mouth of one; a black stick-like form clogs the mouth and throat of another and fingers poke the eye socket and mouth of a third. She told me that her head was filled with ‘this messy crap of guilt and anger’, and that she had to get rid of it. In 1981, a series of massive heads covered by hands provoked Peter Schjeldahl to describe them as ‘from the very backbrain depths’ moving towards a ‘shivery force – the hint of a diabolical sense of humor, a strange, cold joy’.

Along with the dark side, there was indeed humour, joy and energetic enthusiasm in Rothenberg’s paintings. When in the ’80s she switched from using acrylics to oil paint a new exhilaration emerged in her brushstrokes, as if mirroring the usually forceful, tornado-like and exuberant temperament of the artist. And, of course, in the late ’80s and ’90s, there were the excited and colourful forms that came out of her move from New York to Galisteo, New Mexico, to live with her new husband, Bruce Nauman. The high desert landscape inspired more colour, new emotions, as well as literal action. Rothenberg and Nauman lived alone on a large section of land. Animals were everywhere around the ranch: dogs, goats, snakes, some sheep, cattle, and yes, horses. Susan loved them all and seemed to be in constant communication with them. I dare anyone to find a photograph of her without an animal in it.

Pink Raven (2012), Susan Rothenberg. Hall Art Foundation. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York; © 2020 Susan Rothenberg/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Animals once again became emotional surrogates, jumping, flying, bucking and sometimes just watching. ‘When I’m in the studio, I’m alone except for the animals,’ she told me. ‘I look at the canvas tacked to the wall and feel like I’m watching my mind. And the dogs look at me wondering what I’m looking at. And then I look at them and they end up being a part of the painting.’

Her last gallery shows were moody, including some large, menacing-looking black birds perched on limbs or just standing sentinel, guarding some deeper knowledge. One of Rothenberg’s last paintings was large and dramatic, depicting a wild woman, hair flying, hands pounding a piano. It is a very strange painting that is excited and dark, as if we are being a given a glimpse of pure mental and physical emotion. It is the work of an artist who was resolute and fearless in her expressionism. It’s work we will sadly miss.

Michael Auping has curated several solo exhibitions of Susan Rothenberg’s work, including her first museum exhibition in 1979 at the University Art Museum, Berkeley, and a touring retrospective which originated at the Albright Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, in 1992.