Abstraction has always had macho associations. It’s not just down to the atmospheric black and white photographs of rugged and brooding Abstract Expressionists, which did much to establish the artists in the imagination of the art world. It relates more profoundly to the cerebral theories of Malevich or the spontaneity of Pollock’s ‘drip’ paintings. These are qualities that, historically, have been assigned to men and the grand defences of abstraction as an art form – by critics such as Clement Greenberg, who rarely wrote about women – have much to answer for on this count.

The feminist art historian Linda Nochlin challenged the formation of such status quos in 1971, in her essay ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’. She points out that when we choose to believe in ‘the apparently miraculous, nondetermined, and asocial nature of artistic achievement’ that ‘must always out, no matter how […] unpromising the circumstances’, we overlook obvious social and institutional barriers. ‘Surface Work’, a survey show of women abstract artists across Victoria Miro’s Mayfair and Wharf Road galleries, reveals an alternative history of how much women have already achieved.

Non-Objective Composition (c. 1920), Liubov Popova. Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art

From the examples of the more than 50 artists in this show – some relatively unknown and others household names – it is obvious that women approached abstraction with just as much curiosity, innovation and overall gusto as men. Nochlin criticises the temptation to read art by women as evidence ‘of a distinctive and recognisable feminine style […] based on the special character of women’s situation and experience’. The temptation is particularly strong in the case of abstract art, where we are already inclined to seek hidden depths and emotions within the non-figurative forms. But to attribute a certain composition, brush movement or palette to an irrepressibly feminine intuition, softness, or domesticity, is horribly flattening.

Take Kusama’s INFINITY-NETS (HNBKU) (2012), a proliferating web of thickly impastoed arcs made by the repeated flick of a wrist. Kusama launched herself on the New York scene by exhibiting five of her Infinity Nets at the Brata gallery in 1959. Donald Judd wrote in ARTnews, ‘Kusama is an original painter’ whose ‘strokes are applied with a great assurance and strength’. The repetition in the Infinity Nets is more commonly seen as an expression of Kusama’s need to recreate the hallucinatory episodes she has experienced since childhood, in which her surroundings pulsate and dissolve into a self-obliterating field of spots. Both Judd’s reading and the standard psychobiographical analysis of Kusama’s work are surely gendered, but at least the differing interpretations focus on the artist as a distinctive figure and, taken together, they offer a more complete picture of Kusama’s complex inner psyche and self-possessed outward ambition.

Just next to Kusama in Mayfair is a wonderfully discreet hand-drawn grid by Agnes Martin, which might easily be overlooked. Untitled (1995) mimics the serial forms of 1960s minimalism, but if you lean in closer you’ll notice the odd smudge or swerving line; subtle subversions of a detached, industrially-produced aesthetic. The oldest work on show here is Liubov Popova’s Non-Objective Composition (c. 1920), in which a white circle is overlapped by a golden orb that glistens in the shiny gouache. A crosshatch of black lines in India ink gives the composition both balance and a dash of dynamism.

Untitled (1957), Gillian Ayres. Courtesy Gillian Ayres and Alan Cristea Gallery, London; © Gillian Ayres

The three rooms of mostly contemporary art at the Wharf Road gallery display works that demonstrate very diverse forms of abstraction, with rather mixed results. Among the works are some trauma blankets from Dala Nasser, Fiona Rae’s saccharine Kandinsky – and what looks like a coffee-stained sheet, for which one of the materials listed is ‘Bub’s urine’, by Lucy Dodd. The highlight must be the late Gillian Ayres’s Untitled (1957), a slim horizontal canvas in which little patches of rich colour grow upwards into bold swathes. The paint sits on the surface of a grainy board, often in thick clumps, but elsewhere as a flutter of creases like the wrinkles in wet sand, budding and swelling like multi-coloured mould. The effect is at once artificial and organic.

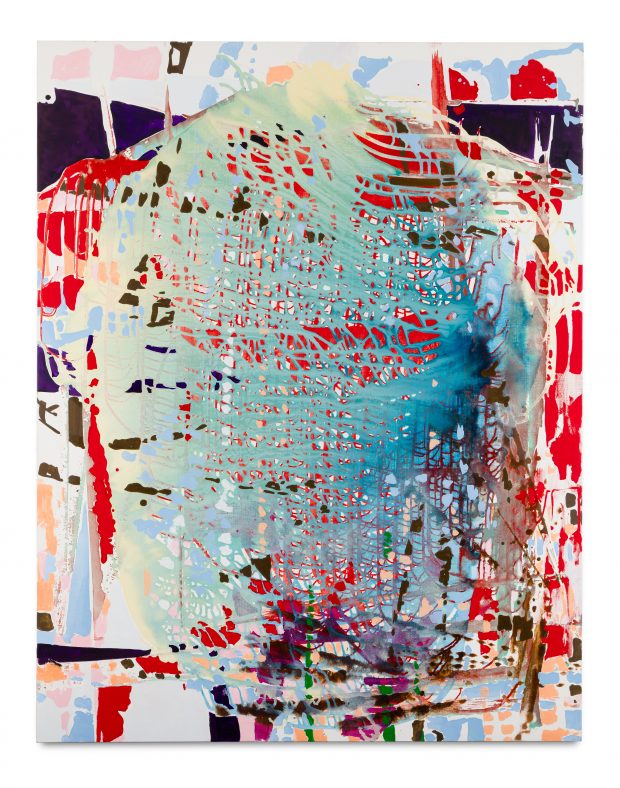

Portrait (captive) (2015), Jackie Saccoccio. Courtesy Van Doren Waxter, New York; © Jackie Saccoccio

Jackie Saccoccio’s vibrant Portrait (Captive) (2015) is achieved by dripping paint into long strings that droop, bunch and stretch like a loosely woven scarf. Other works push past the limitations of a flat, four-sided canvas. Sarah Cain’s Moonlight (2011) adorns the untouched canvas in unexpected ways, balancing objects along its top edge and strewing beads and strips of colourful canvas across its plane. For Deflated IV (White) (2009), Angela de la Cruz has abandoned the stretcher entirely, leaving a heavily painted, shiny white canvas to sag and fold into a voluminous structure that crosses the boundary into sculpture.

‘Surface Work’ takes its title from Joan Mitchell’s response to a journalist who asked her to define her technique: ‘Abstract is not a style. I simply want to make a surface work.’ In its abbreviated form, the exhibition title has troubling connotations that are in danger of removing women artists still further from their, apparently profound, male contemporaries but perhaps Mitchell was wary of being contained into a context that was already defined by men. What Mitchell said next underscores the difficulty of trying to appraise what women have contributed to abstraction, specifically as women: ‘This is just a use of space and form […]. Lots of painters are obsessed with inventing something. When I was young, it never occurred to me to invent. All I wanted to do was paint.’

Deflated IV (White) (2009), Angela de la Cruz. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice; © Angela de la Cruz

‘Surface Work’ was at Victoria Miro, Wharf Road until 19 May and is at Victoria Miro, Mayfair until 16 June.