Static (2009), the paradoxically named video installation that opens the Steve McQueen retrospective at Tate Modern, jerkily loops around the Statue of Liberty at close range. McQueen’s study of the national icon is less triumphalist than it is ambivalent. Shot from a helicopter from on high – you can hear the choppers – Lady Liberty looks less ministerial than haunted. Her copper-green face bears slight marks of physical decay, and blue-toned city landscapes and sunlit Hudson River encircle her from a distance. In recent years, the statue has been at the centre of fresh debates on the meaning of America. On 4 July 2018, the activist Patricia Okoumou scaled its base in protest against the separation of immigrant families at the nation’s border. In August last year, the acting director of US Citizenship and Immigration Services, Ken Cuccinelli, proposed an amendment to the statue’s placard, which famously bears lines from poet Emma Lazarus’s The New Colossus: ‘Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’ It should read, Cuccinelli countered, ‘Your tired and your poor who can stand on their own two feet and who will not become a public charge.’

Static (still; 2009), Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery; © Steve McQueen

Shot shortly after the statue reopened to the public following the 9/11 attacks, Static could not have anticipated these controversies. Still, there’s an uncanniness in the way McQueen’s film lingers around its subject, scrutinising it with such close, unsparing – but also contemplative – attention. In this sense, it’s an archetypal work of the British artist who made his name as a Turner Prize-winning gallery star before venturing into the Hollywood mainstream as director of Widows (2018), Shame (2011), Hunger (2008), and the Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave (2013). Static takes a perennial subject – the meaning of America (likewise, McQueen’s feature films have examined Bobby Sands’s hunger strike; sex addiction, slavery, and women living in the shadows of dubious husbands), and subjects it to slow, steadfast examination, all the while avoiding didacticism or melodrama. Lady Liberty is often either a vaunted symbol of the grand American dream or an embarrassing indictment of all that the nation has failed to become. In Static, she is simply – or not so simply – a statue.

This rejection of overt metaphor, and valorisation of physical looking over runaway interpretation, may be what McQueen means when he talks about uncovering ‘truth’. The exhibition, which features just over a dozen of his works made over the past two decades, greets incoming visitors with a wall text citing the artist: ‘The fact of the matter is I’m interested in a truth […] It’s about not blinking.’ Though what is the nature of that truth, and the form of that looking? Western Deep (2002) offers a fly-on-the-wall view of workers in TauTona, the world’s deepest gold mine located just outside Johannesburg; in 7th Nov. (2001) McQueen’s cousin Marcus recounts the day he accidentally shot and killed his brother. Again, the artist opts for an understated, reflective way of framing these painful truths of life. Western Deep, shot on Super 8mm film (‘I wanted to shoot on something that had grain […] I wanted something that the viewer could hold onto, that had texture’), opens to a pitch-black descent down the mine’s 3.9 kilometre-deep elevator, set against the metallic clang of machinery. Then, grainy scenes of isolated labour done by young black men are overlaid with periods of absolute silence interrupted by deafening intervals of drilling. The result is eerie, distant. Likewise, 7th Nov. eschews the obvious cathartic offered by talking-heads-style confessional interviews. Instead, it sets a recording of Marcus telling his story against a still image of the top of his head as he’s lying in repose, his skull lined by a long scar. I find myself paying more attention to what is heard than seen; I listen to Marcus’s pointed silences, and sense the subtle demands for empathy in the way he intermittently ends his sentences: ‘Do you understand?’

Digitally scanned file from End Credits (2012–ongoing), Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery; © Steve McQueen

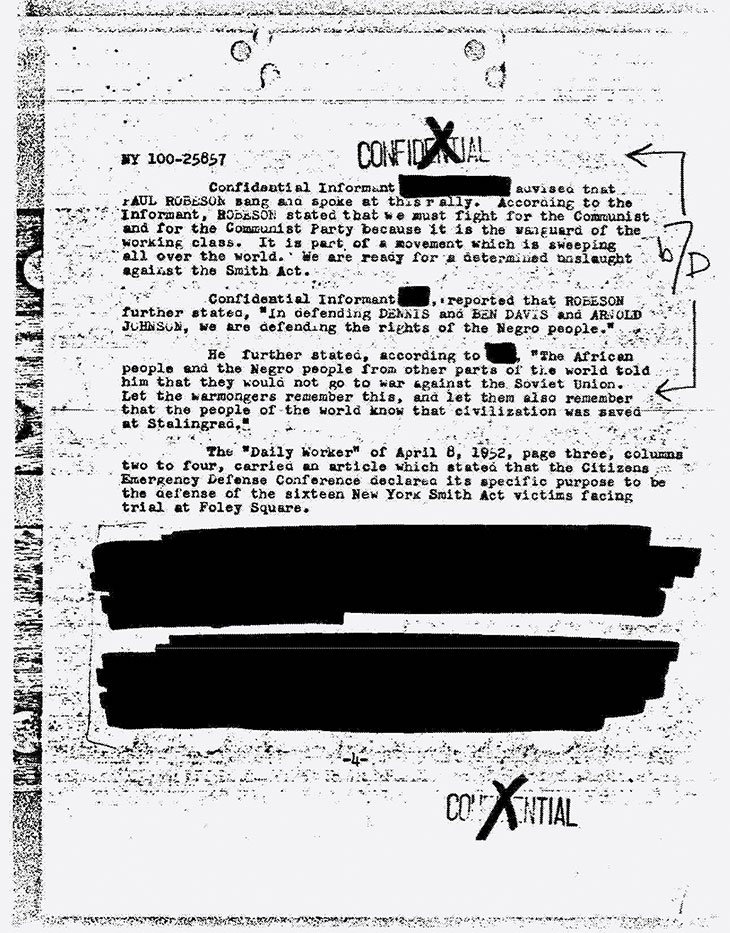

The truth-telling artist, in many popular imaginations, is associated with the renegade – often white – bad boy, inflicting on his audience a relentless, indiscriminate exposure to the ugly, the depraved, and the sensational. (McQueen was at Goldsmiths near the tail end of the YBAs: ‘I went for a drink with some [of those] people once. That was it. It was… isolating.’) McQueen’s approach is more restrained, leading you to a truth framed by what is not there as well as what is; what is foreclosed as well as what is possible. Many of his subjects, after all, have not been able to unleash themselves on to the world on their own terms. In the final video of the exhibition, End Credits (2012–ongoing), McQueen remembers Paul Robeson, the African-American baritone singer, actor, and activist whose work with left-wing anti-imperialist organisations abroad and the Civil Rights Movement at home saw him fall into disfavour with the US government (in 2014, it was reported that McQueen was preparing to make a feature film on Robeson but there has been little news of it since). The colourful life of this preternaturally accomplished multi-hyphenate, whose activism took him to the coal mines in South Wales and Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War, is instead conveyed in End Credits by a seemingly infinite scroll of black-and-white FBI reports on his political work, relationships, and day-to-day actions. An impersonal male voice with a nasal edge narrates the bare facts of these heavily censored documents, listing their dates and the hazy contours of their findings. But a woman’s voice cuts in before anything gets too interesting, such as when her counterpart is about to reveal the names of the FBI’s sources. ‘Redacted.’ It’s the only word she says, set on a loop.

‘Steve McQueen’ was originally scheduled to run at Tate Modern, London, until 11 May. It reopens on 7 August (until 6 September).