Everyone loves to hate at least one artist. My particular bête noire is Stanley Spencer. There’s something about his roly-poly figures, his whimsical religious scenes and his obsessive nudes that puts me in mind of a village pervert. As I see it, his work is sentimental and disturbing, creepy and cringe-inducingly wet. It makes my skin crawl.

I was invited to the reopening of the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, Hampshire. The building is home to a series of paintings by Spencer, which took the artist six years to create and is acknowledged as his most important work. Heavily inspired by Giotto’s frescoes at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, these paintings were Spencer’s response to the Great War, stuffed with religious allusions and imagery based on his own memories of the conflict.

Strolling up the red brick path that leads from the road to the chapel, the first thing you notice is the tall central block. Lionel Pearson’s design is an example of the cheery utilitarianism applied to any number of suburban British buildings from the inter-war period. It could be a cinema, a tube station, a town hall, even. But then you notice its symmetrical annexes, built in an approximation of the Arts & Crafts style. It’s a not entirely successful conversation between Charles Holden and William Morris.

I am not looking forward to my visit. But as I’m shown into the chapel, something extraordinary happens. I wouldn’t call it an epiphany, exactly. But it certainly made me look at Spencer’s paintings in a different way.

The chapel itself is tiny – it fits only about 25 people. The building was commissioned by Spencer’s patrons Louis and Mary Behrend in the early 1920s as a tribute to the conflict’s forgotten dead. More specifically, it was to be a memorial for Mary Behrend’s brother, Henry, who had fought in the Salonika campaign and died of malaria shortly after hostilities ceased.

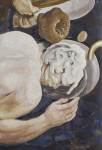

Map Reading, Stanley Spencer, at the Sandham Memorial Chapel Image courtesy John Hammond, National Trust © The Estate of Stanley Spencer; The Bridgeman Art Library

Salonika, where Spencer too had served with the Royal Army Medical Corps, was ‘the forgotten front of the forgotten war,’ remembered as a mere sideshow to the campaigns in Belgium and Eastern Europe. It nonetheless sucked in around a million soldiers from nine national armies.

There were a vast number of casualties, and malaria was the biggest killer, incapacitating around 40% of the 300,000 strong Franco-British expeditionary force. By the time he arrived in Greece in 1916, Spencer himself was no stranger to the human cost of war. He had joined the Medical Corps the previous year, and was immediately posted to the Beaufort Hospital in Bristol, where he served as an orderly.

Many of the paintings in the chapel draw directly on his experience at the hospital; the first in the series shows a lorry-load of wounded soldiers arriving at the gates of the Beaufort, which are being swung open by attendants. The perspective is bizarre, almost a premonition of how a CCTV camera might record the scene. You’re forced to crane your neck to get a sense of where you stand as an observer.

Stanley Spencer’s paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel, on display at Somerset House (2014) Image courtesy Sam Roberts

Others – such as the enormous The Resurrection of the Soldiers – are a hallucinatory representation of the frontline. In the latter painting, which shares its theme with The Cookham Resurrection, the artist’s most famous work, dead soldiers rise from their graves, uprooting the white crosses that marked them into a jumble. Unusually for a resurrection painting, Christ himself is not the focus; he sits in the distance, watching quizzically as the dead claw their way up through the mud.

The horizon is immediately familiar. Although Spencer would have preferred to set the series in his beloved hometown of Cookham, the Behrends insisted that the paintings should be in some way specific to Burghclere. Thus those hills in the distance are based on the view of Watership Down one sees from the entrance to the chapel.

You could spend weeks in here searching for details and hidden significances. The qualities that can seem nauseatingly twee in Spencer’s work are here transformed into something else entirely, and grouped together in the chapel, the series is immensely powerful. I will never be a fan of Stanley Spencer as an artist. But I can at least acknowledge that at Sandham, he created a masterpiece.

The Sandham Memorial Chapel is a National Trust property in Burghclere, Hampshire