Some have great exhibitions thrust upon them. That was my good fortune as curator of ‘Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light’, soon to open at the National Gallery in London. There hasn’t been a major exhibition of works by Joaquín Sorolla (1863–1923) in London since 1908. Back then, at the fashionable Grafton Galleries in Mayfair, he was unabashedly advertised as ‘The World’s Greatest Living Painter’. As opposed to in the United States, however, where success was instantaneous, Sorolla never caught on here. He is represented in UK public collections today by a few, scattered pictures, none of them major, none at the National Gallery, none at Tate. If Sorolla figures in British discussions of painting around 1900 at all, it is mostly in fleeting comparisons to his friend and fellow wizard of the paintbrush, John Singer Sargent.

Strolling along the Seashore (1909), Joaquín Sorolla. Museo Sorolla, Madrid

In 2016 the exhibition ‘Sorolla and the Paris Years’ in Munich caught our attention. The artist has even less of a track record in Germany than here but, unexpectedly, it turned out to be an enormous public and critical success. Similarly, the occasional Sorollas included in Royal Academy survey exhibitions in recent years have always stirred comment. To discover Sorolla today, it seems, is to be captured by his bravura technique and the freshness of his vision, even if his name tends to elicit little more than a flicker of recognition. And so we began to talk about a Sorolla exhibition in Trafalgar Square. Gabriele Finaldi, director of the National Gallery, had overseen the definitive Sorolla retrospective exhibition ten years ago in his former position at the Prado in Madrid. He knew the leading scholars, collectors, dealers and curators, not least Blanca Pons Sorolla, the artist’s great-granddaughter and doyenne of Sorolla studies.

Over the past few decades the National Gallery has sought to expand the modernist canon by introducing the British public through exhibitions and, more rarely, acquisitions to new or overlooked painters and traditions – Russian, Italian, Nordic, Australian, American. Sorolla is the representative figure of Spanish painting between Goya and Picasso, an interregnum barely known about here; we realised that all the elements were in place – not least the ability to engage the experts and to borrow the masterpieces – to ‘do’ him on a scale commensurate with the artist’s own vaulting ambitions. We got the go-ahead in 2016 and set to work. Pons Sorolla came aboard as consultant, sharing her acute insights, catalogue raisonné of paintings (in progress) and chronology of the artist’s life.

And They Still Say Fish Is Expensive! (1894), Joaquín Sorolla. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Born in Valencia, the son of modest shopkeepers, Sorolla was determined from an early age to establish himself as an artist on the world stage. His strategy was to send large-scale paintings, often on dark and troubling social themes, to major exhibitions at home and abroad. Another Marguerite! of 1892 – the subject is infanticide, the title an allusion to Goethe’s Faust – went to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago the following year and became his first work to be sold in America. And They Still Say Fish is Expensive! (1894), on the perils of life at sea, was acquired by the Spanish state when the artist was 31. Other exhibitions and sales to public collections followed, in Paris, at the Venice Biennale and in leading art capitals. Sad Inheritance of 1899 – an unforgettable image of disabled children making their way on crutches to bathe in the sea – was awarded a gold medal at the Universal Exposition of 1900 in Paris. These early pictures have been brought together in London, introducing an artist whose gaze on the ills of the world was pitiless – he insisted he painted only and exactly what he saw – and full of pity for the downtrodden.

Running Along the Beach, Valencia (1908), Joaquín Sorolla. Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias, Oviedo

They stand in startling contrast – I hope our installation shows this – to the untroubled, even joyous paintings that followed after 1900, on which Sorolla’s international popularity has been based. Here we are transported to the seashore at Valencia or San Sebastián to observe beautiful women in white dresses and wide hats strolling along the sand in brilliant sunshine; naked, carefree boys gambolling in the waves; fisherfolk hauling their boats to shore as the low evening sun turns the water to flickering gold. Sorolla’s dazzling technique was set free by sunlight. He found he could capture every evanescent effect with swift, confident, precise brush strokes. Increasingly successful and wealthy – during five months in America in 1909 he sold 195 paintings, portrayed the president, and met his Medici, the philanthropist Archer Huntington, founder of the Hispanic Society of America in New York – he turned more and more to his wife and three children as subjects of an art extolling bourgeois domesticity, the pleasures of the garden, summertime never fading.

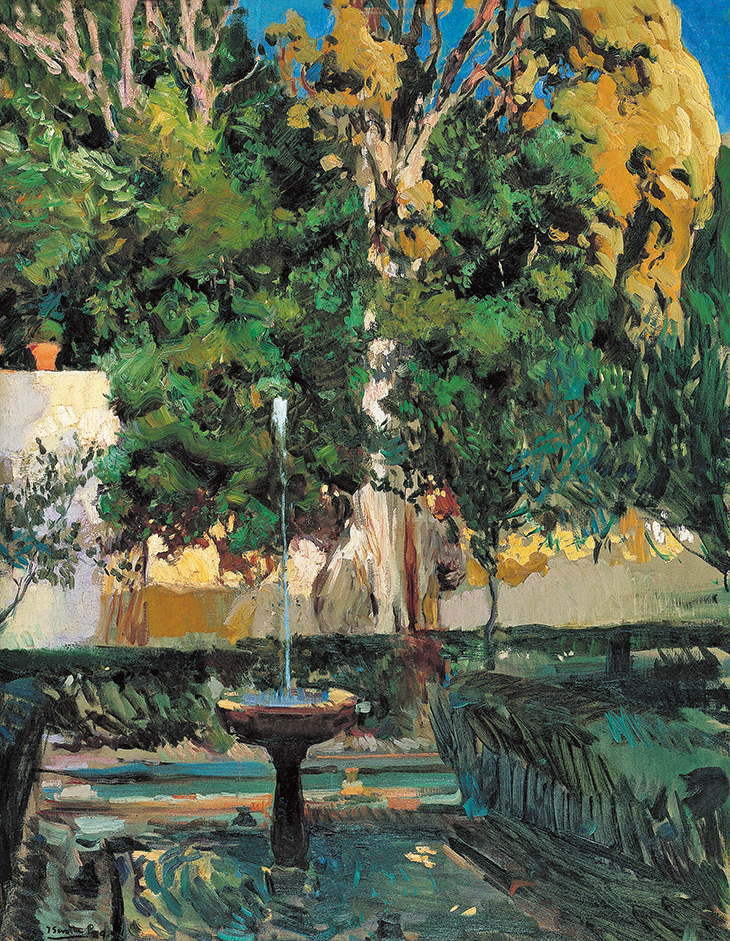

The Cypress of the Sultana, Genaralife (1910), Joaquín Sorolla

At the same time he embraced the Spanish painting tradition of which, the critics increasingly told him, he was the leading modern exponent. His brooding portraits of Spanish worthies, expressive countenances emerging from studio darkness, owe formative debts to Velázquez and Goya. His startlingly intimate Female Nude of 1902 – the model is his wife Clotilde – derives from his study in this country of the former’s Rokeby Venus. And then in 1911 Huntington gave Sorolla the opportunity to secure his reputation as the painter sans pareil of his homeland, commissioning a vast cycle, Vision of Spain, hallucinatory in its intensity, to decorate the library of the Hispanic Society. Our exhibition, which travels to the National Gallery in Dublin in August, includes four life-size preparatory studies from the Museo Sorolla, Madrid, made as the artist travelled the country, posing peasants in colourful local costumes and jewellery. We also have distinctive regional landscapes painted along the way; the light, atmosphere, and tonalities of earth and sky unmistakably Spanish.

Sorolla worked on Vision of Spain until 1919, when he fell ill. The cycle was installed in New York only in 1926 and remains a too-little-known wonder of the city. By then, however, the critics were more apt to cite Picasso, Miró or Dalí when the discussion turned to modern Spanish painting.

‘Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light’ is at the National Gallery, London until 7 July.

From the March 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.