Seamus Heaney HomePlace in the village of Bellaghy, County Derry, isn’t exactly a museum. It’s light on original manuscripts, most of which reside at Emory University in Atlanta or in the National Library of Ireland. There aren’t many artefacts either. A satchel and a school desk; an old-fashioned fountain pen dangling from a wire in a glass case, a mass-produced holy relic. It’s either the pen Heaney used as a boy and wrote about in ‘The Conway Stewart’ from his last collection, Human Chain (2010), or a pen very much like the one from the poem, though it hardly makes a difference. Nearby, other Heaneyish bric-a-brac: an old iron, snowshoes, butter paddles, a water pump. On the way out of the centre, almost hidden away, Heaney’s old duffel coat looms on a hanger behind glass, like one of Joseph Beuys’ felt suits or an installation by Jannis Kounellis. The absence of the human figure who hasn’t been there all along is suddenly laid bare.

Exhibits at Seamus Heaney HomePlace in Bellaghy, County Derry. Photo: Tourism Northern Ireland

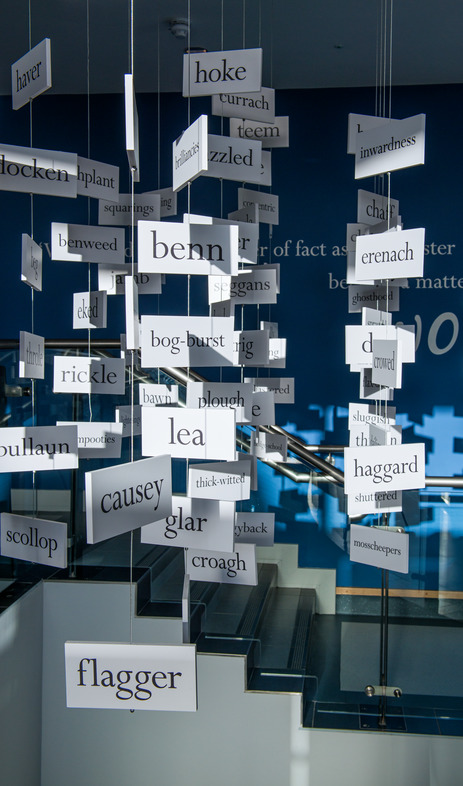

It is wittily done: the one object with a truly auratic force comes after, but is also much more trivial than, the reproductions that dominate the main exhibition. The experience of the core content of the HomePlace is less like visiting a museum and more like reading a volume of Heaney’s selected poems with extensive multimedia annotations. I have never been to a writerly tourist attraction that pays such faithful, accurate and thoughtful attention to the texts themselves. In the ‘People and Place’ zone downstairs, the visitor can walk through Heaney’s poems of family, childhood and the local landscape in great detail. The poems are reproduced unabridged with careful referencing, and read in full by Heaney himself on the audio wand that makes him a seductive presence, whispering in your ear as you work through the exhibition. And the images and texts that frame the poems are genuinely instructive and enlightening. A confirmed townie, I had been acquainted with words like ‘flax-dam’ or ‘harvest bow’ for years from Heaney’s poems without really knowing what these things were; it turns out the poems work better when you do. There are aspects of Heaney that don’t lend themselves to this treatment: Heaney the scholar-poet, the classicist, the translator, the writer of allegorical, Eastern European-style poems such as ‘From the Republic of Conscience’ (The Haw Lantern, 1987). But as a way of encountering the poems rooted in Derry, it works splendidly.

Exhibit at Seamus Heaney HomePlace in Bellaghy, County Derry. Photo: Tourism Northern Ireland

HomePlace stands on the site of the former Royal Ulster Constabulary barracks. Stone from the original perimeter walls has been incorporated into the structure of the building; some of the blast-proof steel fences have been re-used in the carpark. It is a helpful reminder of how just near at hand the threat of violence is in Heaney’s work, and how precariously won the moments of comfort and reconciliation were. The contents of HomePlace, and the Heaney landmarks in the neighbourhood, mostly avoid the blandishments and distortions of the heritage industry by remaining local, small-scale and ongoing. Visiting them almost feels invasive.

Seamus Heaney HomePlace in Bellaghy, County Derry. Photo: Tourism Northern Ireland

Local tour guide Eugene Kielt starts a trip around Heaney country in the churchyard at the other end of the village. Heaney’s grave stands next to the family plot in which, over the course of 50 years, Heaney’s brother, aunt, mother, father, aunt, aunt, and sister were buried. The brother is Christopher, run down by a car in his fourth year and commemorated in ‘Mid-Term Break’ (Death of a Naturalist, 1966) and ‘The Blackbird of Glanmore’ (District and Circle, 2006). Nearby lie many of the ‘big-voiced’ Scullions, Heaney’s cousins, recalled in ‘The Strand at Lough Beg’ (Field Work, 1979) and in the introduction to his 1999 translation of Beowulf.

Next stop: the farm still run by Heaney’s brother, Hugh, the dedicatee of ‘Keeping Going’ (The Spirit Level, 1996) – and here’s Hugh now, the absolute spit of his brother, doing something involving a tractor with another brother, Colum. We trundle over for a chat, have a photograph taken with them, are shown the brewery they have set up on site with the help of Hugh’s son-in-law, and given a bottle of ‘Heaney, Irish Blonde’ to sample. (The comma in the beer’s name matters: a nod to the poet’s feel for punctuation at the end of a line.) We drive on to Barney Devlin’s forge, setting for ‘The Forge’ (Door into the Dark, 1969) and ‘Midnight Anvil’ (District and Circle). Eugene strikes the anvil 12 times; it does indeed ring ‘sweet as a bell’.

We carry on out past Lough Beg. Here is the Bellaghy GAA club where Sean Brown was murdered in 1997 – ‘the carpark where his athlete’s blood ran cold’, as Heaney has it in ‘The Augean Stables’ (Electric Light, 2001). Here is Mossbawn, the farm where Heaney was born and spent his first few years, now fairly run down, with a yard full of rusting cars and a dual carriageway within eyeshot. Next to the house: the field where Heaney would play childhood games of football until dark, ‘four jackets for four goalposts’ (‘Markings’, from Seeing Things, 1991). A few metres down the road: the place where Christopher was run over.

The main event of the weekend, coinciding with what would have been Heaney’s 80th birthday, is ‘In New Light’, in the theatre at HomePlace. Adrian Dunbar and Bríd Brennan read a well-judged selection of Heaney’s poems, before the first performance of ‘Anything Can Happen’, a piece by the Arab-American composer Mohammed Fairouz, which sets the text of three poems from District and Circle for choral singing. The texts don’t seem the most apt for musical adaptation (try singing ‘Undead grey-gristed earth-pelt, aeon-scruff’ and ‘Deepfreeze the seep of adamantine tilth’ next time you’re in the shower), but the Codetta Choir make a terrific job of it.

It’s never quite clear what a visitor should want from an encounter with a place that a writer wrote about or lived in. The things one takes from it are rarely the things it had offered, and the disjunction between the everyday banality of the writing life (sitting at desks, using pens, wearing coats) and the intensities and transformations of literature are apt to produce comical effects. In its modest and steady focus on Heaney’s poems, though, HomePlace serves as a generous guide to his imaginative world, and his patch around Bellaghy is as good a place as any for the task that he described, in ‘The Harvest Bow’ (Field Work), as ‘gleaning the unsaid off the palpable’.