Sometime during his last decade on earth while shooting a movie that he’d been planning to make for 40 years, the Indian film-maker Satyajit Ray had a heart attack. The doctors advised him to refrain from work – his son Sandip was dispatched to complete shooting the film – and it would be another five years before he could make a movie again. During this long hiatus, Ray would often lie in bed and complain to his cardiologist about his illness. The doctor would then produce a few photographs of Ray sitting up sprightly at his desk. ‘Come now, you don’t look ill at all!’ the doctor would say. And Ray would cheer up again.

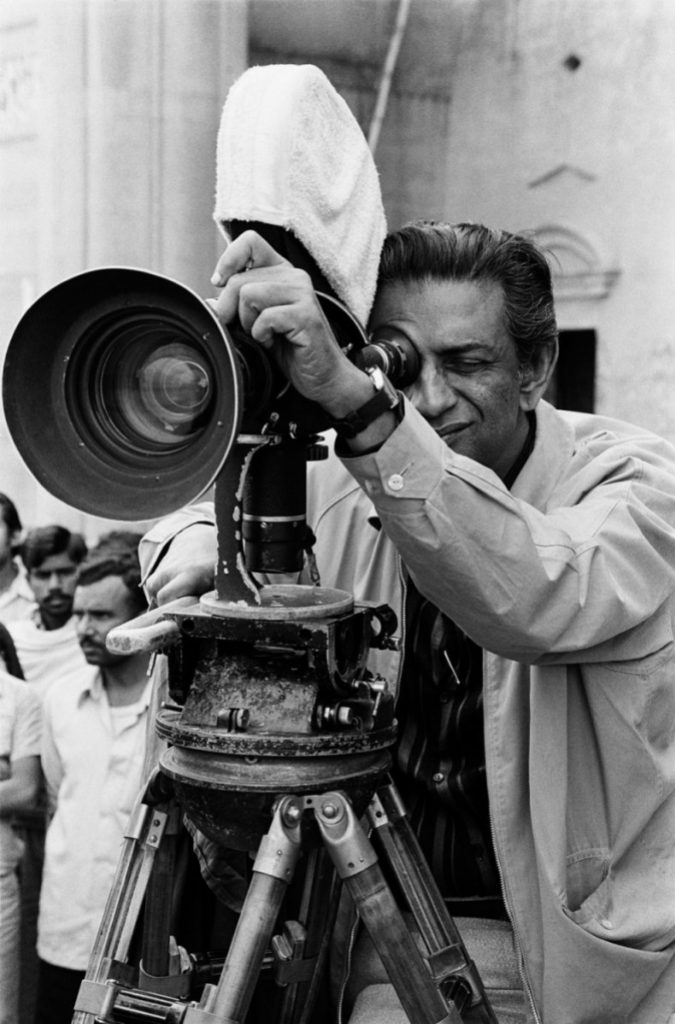

Those photographs were taken by Nemai Ghosh, an amateur theatre actor in Calcutta who started dabbling in images in his thirties when a friend gave him a Canon fixed-lens camera to settle an unpaid loan. He first shot Ray on film without the director’s consent: on a visit to rural Bengal with his friends, Ghosh heard that Ray and his crew were shooting a children’s comedy, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha), in a neighbouring forest. Ghosh ended up at the shoot uninvited one afternoon and finished two rolls of film. Back in Calcutta, when Ray saw the photographs, he was ecstatic. ‘You have done it exactly the way I would have, man,’ he said. ‘You have got the same angles!’

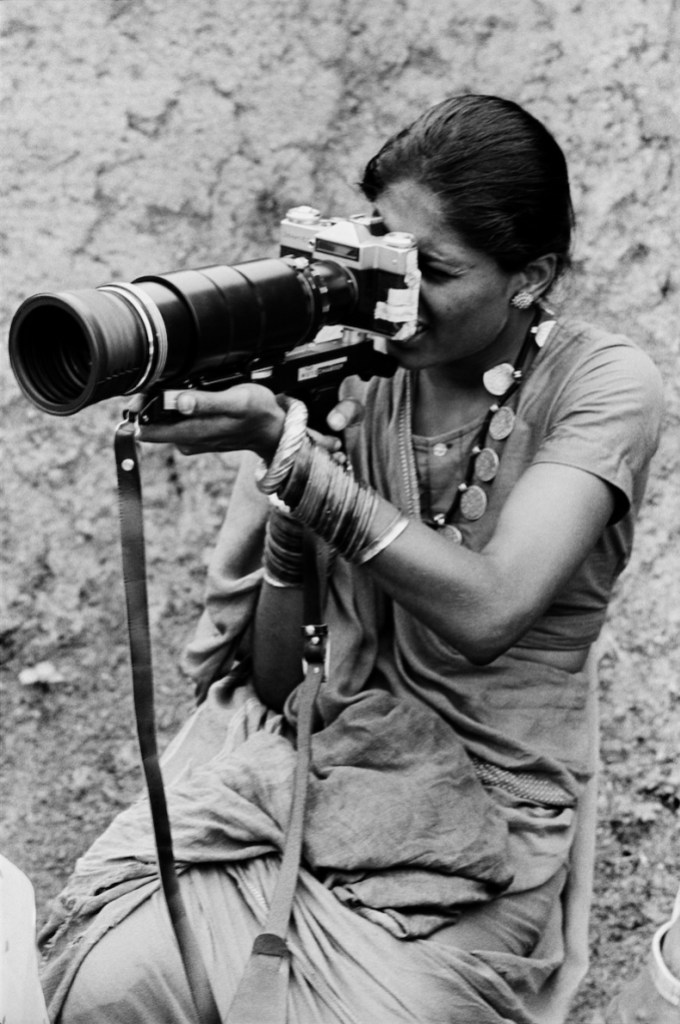

For the next 25 years, Ghosh was Ray’s amanuensis – or, as Ray would introduce him to reporters, ‘a sort of Boswell working with a camera rather than a pen’. He was officially the stills photographer but the work he produced wasn’t exactly publicity material. For one thing, Ray, who had worked as a graphic designer before making the Apu trilogy, drew his own posters. Ghosh’s true subject is the director himself, even when he is outside the frame of an image. When Ghosh catches the actress Sharmila Tagore squinting pensively into the distance, or another actress, Smita Patil, goofing around with a camera on set, you can almost sense that they are slipping into character for a Ray film.

What distinguished a Ray movie from those of his contemporaries? For one thing, the feeling he induced in a viewer that a film is at once a balancing act and more than the sum of its parts. You’re lulled from the opening credits into his vision but it’s hard to tell whether you’re being enticed by the camera, the performances, the music, the story, or the imaginative depth of certain scenes. On set, he was often a martinet about doing things his way. (The actor Victor Banerjee was once asked to weigh up his experiences of working with both Ray and the usually overbearing David Lean. ‘You don’t compare autocracy with democracy,’ he replied.) Ghosh’s portraits apprehend the obstinacy of a man who once remarked that he knew he was a film-maker when ‘I realised I had it in me to take control of situations and exert my personality over other people.’ One moment he is pacing around a crowded railway station capturing the commotion on a sound recorder, the next moment he is wearing glasses and examining the rushes inside the cutting room, while his editor and other crew members flock helplessly around him.

Ghosh perceives Ray as a Chaplinesque actor behind the camera, always the centre of attention at every shoot. Consider this passage from his memoir Manik-da: Memories of Satyajit Ray (2000):

Once, I saw him standing alone and playing a dundubhi (a kettledrum). On another occasion, I saw him lying on the floor and looking at the ceiling; at times I would see him raising his hands above his head in deep contemplation. I noticed that a sign of his deep anxiety or serious contemplation was biting a handkerchief or the pipe. Sometimes, he would whistle a tune, oblivious to the surroundings.

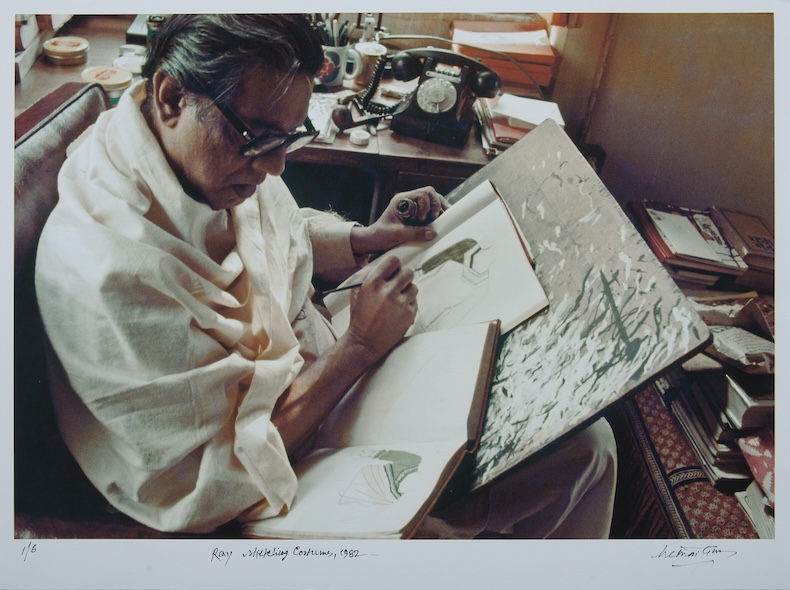

Ghosh would turn up at Ray’s flat on Bishop Lefroy Road for birthdays and wedding anniversaries, and also accompany him on recces and commutes around the city. You can’t help but be struck by the austere diligence of Ray’s appearance in these photographs: the tidiness of the wristwatch on his hands, the sense of freedom evoked by the leather sandals on his feet (he rarely wore shoes on set). Inside his study, Ghosh sometimes finds Ray sketching costumes and props for his characters. On other occasions he’d be hunched over a keyboard synthesiser with a pipe in his mouth, composing the background score for his latest film.

Ghosh’s obsession was mostly a labour of love: he made ends meet by photographing stills for more ‘commercial’ films. With Ray, one senses that he was aiming for a kind of exhaustive visual biography – or even autobiography, since he would regularly scrutinise his contact sheets and mark out the images he thought were decent. ‘This is how I learnt the art of perfect photography from him,’ Ghosh wrote. Each time I encounter Ray staring moodily out of a Ghosh photograph, I remember something Andy Warhol once said about Edie Sedgwick’s hands: ‘Even when she was sleeping, her hands were wide awake.’ With Ray, I suspect his eyes remained wide awake while he slept, dreaming up the next shot in his head.

‘Light and Shadow: Satyajit Ray through Nemai Ghosh’s Lens’ was at the Alipore Museum, Kolkata, in association with DAG, from 18 July–13 September. Faces and Facets: Ray in Colour (2020) and Satyajit Ray and Beyond (2013) are both published by DAG.