Compiling his Reminiscences in the final years of his life, the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) recalled how the coming of America’s Civil War had moved him. Saint-Gaudens had been an aspiring artist, aged 13, and a New York cameo-cutter’s apprentice when the war’s first shots were fired; from the lathe where he learned to cut lions, dogs, and horses into amethyst and malachite, he watched the Federal army gather. ‘From my window,’ he wrote, ‘I saw virtually the entire contingent of New England Volunteers on their way to the Civil War, a spectacle profoundly impressive, even to my youthful imagination.’ Amid strains of abolitionist song, and the marching of feet, one silhouette loomed in his memory: ‘above all, what remains in my mind is seeing in a procession the figure of a tall and very dark man, seeming entirely out of proportion in his height with the carriage in which he was driven, bowing to the crowds on each side. […] the man was Abraham Lincoln on his way to Washington.’ Looking back over decades, the artist’s practised eye picks out Lincoln’s exceptional form, those peculiar proportions that Saint-Gaudens would render in bronze. It also rests on his younger self as sculptor-in-the-making: as the turn of his lathe followed the turn of national events, the newly acquired movements of the young cameo-cutter’s hands found their rhythm in the tramp of soldierly boots and presidential processions.

What was the Civil War to Augustus Saint-Gaudens? The young artist was not radicalised, or even especially politicised by the war: he was no ardent abolitionist like his father, who he cast as something of an eccentric in the Reminiscences. What’s more, he consciously refrained from ‘indulg[ing] in any acrimonious opinions’ and using his memoirs to provide ‘a disquisition on art or the production of artists’, evading the question of his political leanings and personal disagreements even as he abstained from revealing his own artistic rationale. To a modern audience approaching his Civil War monuments – some of the most celebrated and distinctive of their kind – with a critical eye sharpened by the recent removal of Confederate statuary in the southern states, Saint-Gaudens can be hard to interpret.

This isn’t just because monuments to prominent Union statesmen and soldiers, like those Saint-Gaudens produced, seem to justify themselves by virtue of the moral triumphs associated with these figures – however messy that association was in reality. In part, the difficulty arises because the terms of modern critical debate about monuments aren’t readily applicable to Saint-Gaudens’s approach. As the political leanings of men immortalised in granite and bronze come under scrutiny, and with them, the allegiances of the artists behind these monuments, the seemingly apolitical stance that Saint-Gaudens fostered during the turbulence of the Gilded Age resists legibility.

A related difficulty is that Saint-Gaudens’s sculptural realism doesn’t always behave in the way we now expect monuments to behave. To be sure, his major Civil War pieces – the Admiral David Farragut Monument (New York, unveiled 1881), Abraham Lincoln: The Man (Chicago, unveiled 1887), the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial (Boston, unveiled 1897), the General John A. Logan Monument (Chicago, unveiled 1897), and the General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument (New York, unveiled 1903) – inhabit privileged positions in the North’s urban landscapes and, in doing so, assume a degree of narrative authority. Yet the influence Saint-Gaudens’s monuments assert over their surroundings doesn’t primarily rely on the visual symbolism that typically fixes a monument’s version of the past in place – on the mass-produced soldiers that stand sentinel on town squares, or the equestrian generals raised aloft on laurel-decked pedestals and poised steeds. Saint-Gaudens’s meticulously rendered Civil War figures have kinetic potential; they give us the impression that they would like to move. Encouraging us to anticipate Abraham Lincoln’s words; to watch the slow, proud progress of Sherman’s Victory-led charger; to fall into step with the African-American soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts regiment on their way to Fort Wagner, these monuments establish moments of temporal complexity, which make unusual demands of their viewers.

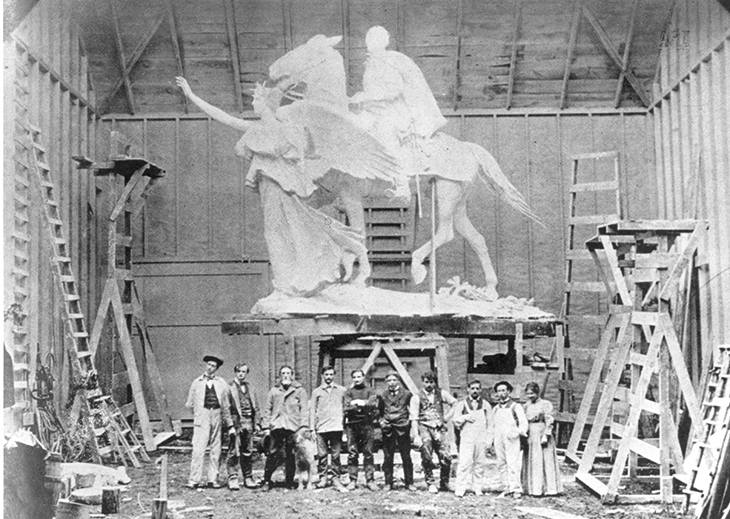

Augustus Saint-Gaudens and assistants in his Large Studio, Cornish, NH, in 1905, with a plaster version of the General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument. Photo: National Park Service

So what was the Civil War to Saint-Gaudens, and what did his abiding memories of it bring to his commemorative work? Like so many young people of his generation, Saint-Gaudens found that the unprecedented events of the Civil War shaped him. In the Reminiscences, the war emerges as a formative influence on his artistic skill, and the habits of his hands. In the tricky business of placing Saint-Gaudens, and of interpreting his responses to the late-century call for commemoration, we should remember that, as this sculptor understood it, his was an art form which attended to, revealed, and depended upon habits – not only those of the sculptor, but the physical comportment of his figures, and their habits of mind. Indeed, the notion of ‘habit’ became central to his conception of the relationship between an individual and their home nation. ‘[H]abit, habit of every kind dominates our lives,’ he told his son Homer: ‘Patriotism, to my thinking, is habit; it’s the habit of one’s country.’ In connecting his first foray into the plastic arts with the ‘heroic and romantic’ acts of soldiers heading south, Saint-Gaudens aligns his innovative sculptural realism with the study and expression of patriotism as it manifests itself through the body – or, more precisely, the bearing and mannerisms of exemplary public figures.

In the decades after the Civil War, such examples were urgently needed. Saint-Gaudens would have been aware of the argument, made by the intellectual and social elite, that the country’s patriotic habits were not fully formed. The intensive period of monument building that spanned the 1880s and 1890s coincided with acute social turmoil, economic inequality, racial violence and political corruption across the US, which raised questions about the integrity of the hard-won Union and the bonds of feeling that held it together. To the genteel reformers and Gilded Age businessmen of the North, who had funds, influence and interest enough to instigate change, monuments commemorating soldiers and generals, and the values they had displayed during wartime, offered one important way of inspiriting individuals with new feelings of citizenly purpose. Monuments were to be habit-altering objects, capable of moulding national feeling in their own image.

Artists and writers had begun to foster such hopes for art’s role in the war’s moral legacy before it had even ended: in 1864, the art critic James Jackson Jarves wrote of the ‘intense need of preserving and perpetuating the public spirit and unity of feeling [the war] has called forth’. Contemplating the war’s commemorative afterlife from Europe, Jarves envisaged social unity issuing from conscientious city planning in the Old World vein. Encounters with beautifully arranged shop windows, or the crafted landscapes promised by Frederick Law Olmsted’s Central Park, he proposed, would prevent ‘internecine convulsions’ by providing ‘lessons in order, discipline, and comeliness, culminating in […] a better understanding of humanity at large, from its democratic intermingling of all classes’. The writer William Dean Howells agreed that public monuments should be sites of moral and social reinvigoration. Commemorative sculpture, he argued, must prove itself ‘adequate to express something of the spirit of the new order we have created here’. Where Jarves looked forward to the disintegration of class boundaries on the country’s carefully designed streets, Howells evoked the ‘rights to citizenship’ promised to African Americans in the wake of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: socialising with statuary might help the general public recast itself as a society comprised of Black citizens, as well as white.

Saint-Gaudens’s Civil War sculptures undoubtedly participate in the utopianist approach advanced by Jarves and Howells. In the ways they invited interpretation by the host of orators, businessmen, intellectuals, and citizens who flocked to their bases on dedication days and anniversaries, his attentively rendered statesmen and soldiers became instrumental to establishing the war’s legacy as a usable past. Imbuing them with vitality, Saint-Gaudens generated a form of mnemonic momentum in his commemorative figures – an impetus that prompted some onlookers to reckon with their own commemorative attitudes.

Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, installed in Boston in 1897. Photo: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

To William James, the Harvard psychologist who gave its dedicatory address in 1897, Saint-Gaudens’s Robert Gould Shaw Memorial offered viewers a unique opportunity to break the habits of militarist aggression and conservative hostility towards outsiders – racial, political, national – that he saw threatening ‘the public peace’. This bas-relief certainly broke with artistic conventions: defamiliarising the traditional equestrian statue, it depicted the white, Bostonian Colonel Robert Gould Shaw riding alongside the African-American troops of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, one of the first northern Black regiments to join the war effort, and which won fame for their ill-fated attack on Fort Wagner, a Confederate stronghold in South Carolina (272 of the regiment’s 650 men were casualties of the battle). While critics such as Albert Boime have levelled charges of racism against Saint-Gaudens for his elevation of Shaw above his men, recent interpretations by Nancy K. Anderson and others have lauded Saint-Gaudens’s use of a variety of Black sitters to model the men of the 54th, and the attention he devoted to working against pervasive racial stereotyping to represent the Black troops realistically, as individuals contributing to the onward march of the group.

Experiencing the sculpture in situ only confirms the extent of Saint-Gaudens’s innovation. The memorial sits at the north-eastern corner of Boston Common, across the street from the Massachusetts State House (at present the bronze is undergoing conservation work at Skylight Studios in Woburn, MA, as part of a significant civic renewal project). On entering into its recess from the sidewalk, the viewer’s sense of the composition as a coherent whole is complicated, since, in closer proximity, our eyes align with its forest of legs and hooves. The sculpture catches us up in its irresistible forward motion, rearranging the notions of hierarchy we might otherwise take from its composition. Does Shaw lead his men, or is he swept up by his men’s determined pursuit of emancipation? Delivering his address, William James found in this image a meeting of the two: in passing up a commission in the all-white 2nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment to ‘head [the] dubious fortunes’ of this new, Black regiment, and risking the ridicule or failure of this unprecedented venture, James claimed, Shaw had exhibited ‘a lonely kind of courage (civic courage as we call it in peace-times)’. The habits of thought and social circumstance that might otherwise have made him reject this challenge had come into contact with ‘the opportunities, which the accidents of history [threw] into [his] path’: caught up in the emancipatory turn the war had taken, James implied, Shaw went against his better judgement to create a new course of action, one which would empower the men who marched with him. In the battle for a more tolerant and cosmopolitan society in the America of the Gilded Age, citizens might find the blueprint for a ‘lonely kind of courage’ to resemble Shaw’s in the motion of Saint-Gaudens’s memorial.

For all its progressive intent, James’s speech didn’t linger on the bravery of the African-American veterans – the men who had saluted Saint-Gaudens’s image in formation on the day of the unveiling. As the African-American educator Booker T. Washington would remind audiences in the day’s second oration, this monument stood ‘for effort, not for victory complete’: the real monument to Shaw and his men was being constructed elsewhere. ‘Tell them,’ he encouraged his Black listeners, ‘that, as grateful as we are to artist and patriotism for placing the figures of Shaw and his comrades in physical form of beauty and magnificence, […] the real monument, the greater monument, is being slowly but safely builded among the lowly in the South, in the struggles and sacrifices of a race to justify all that has been done and suffered for it.’ Washington’s conception of a living monument to the war dead reveals the limits of commemorative media as a vehicle for genteel projects of reform. Freedom was an ongoing process; to monumentalise it was to suggest that it had already been achieved.

In many ways, monumentality would work against Saint-Gaudens’s preoccupation with motion. For while the sculptor often dwelt on moments of becoming, or provisionality, he was also captivated by a strong, nostalgic yearning for the expressions of moral virtue he had witnessed, appreciated and absorbed during the turbulence of the Civil War. We know that Saint-Gaudens experienced this tension because unearthly figures haunt his Civil War pieces: Shaw and his men, for example, are watched, overhead, by what Homer Saint-Gaudens called a ‘flying figure’, who drove his father ‘nearly frantic in his efforts to combine the ideal with the real’. If Saint-Gaudens understood how the war had inspired his art, and his belief that the country’s better angels might shape one’s nature, his works also romanticised the war, to the extent that pieces which opened out democratic possibilities of speech and action appeared, to some viewers, to advocate for ominous forms of conservatism, silence and restraint.

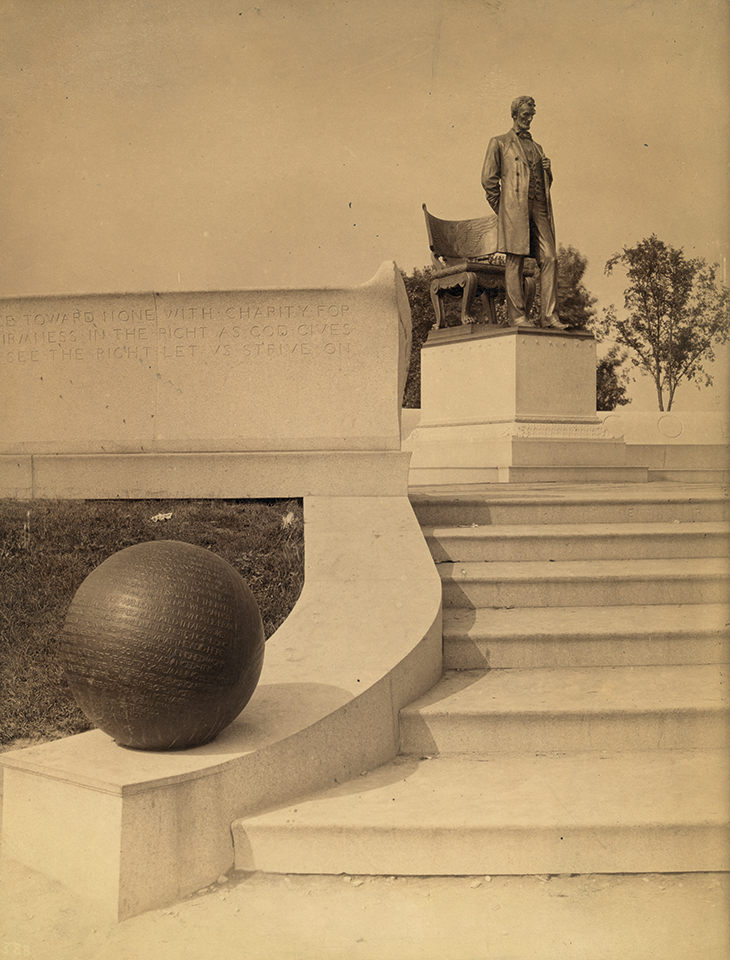

Abraham Lincoln: The Man (1887), Augustus Saint-Gaudens, installed in Lincoln Park, Chicago. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Andrew Horne (used under a Creative Commons licence; CC BY-SA 3.0)

This was certainly true of Saint-Gaudens’s Abraham Lincoln: The Man, which was dedicated in Lincoln Park, Chicago in 1887. Abraham Lincoln has just risen from the chair of state. His eyes stray towards the ground rather than meeting those of the onlooker, although his posture suggests that they could do so at any moment. Taking his lapel in his left hand, and clenching his right behind him, he seems ready to step forth from the plinth and into utterance, a speech worthy of Union. His bearing bespeaks the impetus of his internal logic – a logic of character so faithfully rendered that it also becomes a promise. As Saint-Gaudens asks his audience to invest in Lincoln’s pause – the promise and power of his utterance – he brings them into a close, commemorative communion with Lincoln himself, and invites them to enter into this man’s habits of thought and action.

Lincoln’s unspoken words are what make this an interpretively rich, if deeply ambiguous commemorative work. Its performed pause encourages the viewer to imagine what Lincoln might say to steer the country through present troubles, as he had steered it through the Civil War. Famous fragments of Lincoln’s oratory and written rhetoric, carved into the surrounding exedra designed by Stanford White as well as the bronze globes that flank the figure, suggest the shape the president’s words might take. Representing the development of his policies through the war, these extracts culminate, chronologically, in a line from one of his last speeches, the Second Inaugural: ‘With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on.’ The inscriptions’ sequential sweep seems to bring new words to the tip of Lincoln’s tongue: word and image work together to enshrine his political pragmatism. Yet, in invoking a plan for national reconstruction that Lincoln was never able to begin, the words from the Second Inaugural, like the exedra which, as the art historian Diana Strazdes has noticed, acknowledges Roman tomb-building traditions, draws attention to the poignancy of Lincoln’s silence.

Abraham Lincoln: The Man, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, installed in an exedra by Stanford White, the ensemble unveiled in Lincoln Park, Chicago, in 1887 (photo: 1887–1900[?]). Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The tragedy of Saint-Gaudens’s work is that Lincoln will never speak again, that his words are always already past. The irony of it is the way in which Saint-Gaudens’s immortalisation of Lincolnian deliberation would fall prey to reinterpretation by Chicago’s social elite, who used the monument’s dedication day to fix the president’s memory in place. Funded by the bequest of lumber magnate Eli Bates, the monument’s commission and dedication was overseen by his trustees, a group of businessmen and lawyers whose concerns about growing worker unrest in Chicago prompted them to seek a remedy in the ideal of Lincoln’s statesmanship that was repeated into myth after his death. In his dedicatory oration, Lincoln’s friend, the Illinois lawyer Leonard Swett, drove their message home. Lincoln had not been creative, but cautious: while he sought to honour the ‘vox populi’, Swett argued, Lincoln had not seized victory, or acted impulsively in the people’s name, but ‘watched the operation of the great forces as they gradually but slowly brought order out of chaos and led him on to final triumph’. By venerating the embodiment of Republican patience, the people of Chicago were encouraged to feel an all-uniting affinity with Lincoln the monument – silent, acquiescent, ideal – rather than Saint-Gaudens’s figure of pause, reassessment, and complicated pragmatism: Lincoln the man.

Writing of his own encounter with Abraham Lincoln: The Man in 1905, Henry James, with characteristic obliquity, touched on the genius, and the trouble, of Saint-Gaudens’s sculpture. For the writer who believed that art’s aim must be to ‘compete with life’, Saint-Gaudens had achieved the near impossible: with a ‘mystery exquisite’, his Lincoln brought together ‘the combination of intensity of effect with dissimulation, with deep disavowal, of process’. Saint-Gaudens had captured Lincoln’s essence, the ‘intensity of effect’, James insisted, without leaving any trace of the sculptor’s art. In his absolute fidelity to his patriotic subjects’ habits of body and mind, this sculptor’s figures became, as one critic put it, ‘wonderfully real yet ideal’: magnificent versions of heroic men, suffused with a provisionality born of their willingness to engage with the messy process of democratic action. Saint-Gaudens gave an impetus to realism, even as he invested his works with the moral ideals that emerged with northern triumph; to commune with his figures, for all that some viewers have tried to fix their interpretation, is to reflect on the shape that democracy might take, and with it, the manner and direction of its movement.

From the November 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.