The collections of the Society of Antiquaries largely came together during the first century and a quarter of the institution’s 300-year-old history, following its foundation in 1707. Before the age of our national museums, the Society was the repository for all manner of objects that told stories about the country’s past. Paintings, relics, documents, all manner of physical fragments, were gathered in thanks to the generosity of Fellows and other donors. The present exhibition, the second free public show in the past two years, highlights a curious combination of things that gather around the names of royal figures from the late medieval period to the end of the 16th century.

Portrait of Mary I (c. 1554), Hans Eworth. Society of Antiquaries of London

The portraits are in themselves the most significant collection of their period outside the National Portrait Gallery. Here are images originally from sets of portraits for display in great houses belonging to those of any means from gentry class to aristocracy to merchant grandees. The majority came to the Society thanks to the generous bequest of the Norfolk collector, Thomas Kerrich, in 1828. Here are the brothers Edward IV and Richard III, once long separated but clearly made at the same time because the panels on which they are painted are cut from the same tree. An image of Henry VII may well have been painted as a gift, part of his considerations of re-marrying after the death of his queen, Elizabeth of York. Over the room’s fireplace is the magnificent portrait of Mary I, painted by Hans Eworth in the first winter of her reign. Objects here remind us that people were given likeness of the great through a range of things, for here is a cast of the seal of Mary I and her consort Philip II of Spain, as well as the second great seal of Elizabeth I, part-designed by the famous miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard.

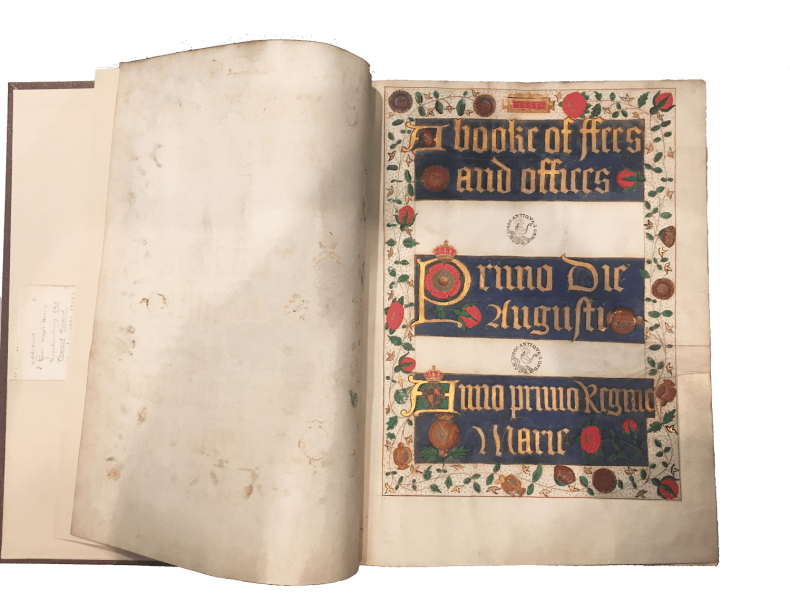

A book of fees and offices (1553). Society of Antiquaries of London

The idea of ‘image’, of perpetuating something of the memory of a royal being, goes deeper however with the objects on view. Here is a lock of hair snipped from the body of Edward IV when his tomb was found at Windsor in 1789, along with a drawing of the ‘event’ of discovery, bringing us close to the fascination in the period for unearthing the past through the remains of famous individuals. A beautiful textile fragment, once said to have belonged to Katherine of Aragon, may be a surviving piece of the pall made for the funeral of Prince Arthur, her first husband. The Tudors came to power through dynastic conflict and a spur left on the field of the Battle of Towton and a great bronze cross found near the site of Bosworth, testify to an earlier, more unsettled time. However, it is finally through documents that the past comes most sharply into focus because they repay close attention. Part of the great inventory of the royal palaces taken at Henry VIII’s death, full of the grand and commonplace objects of court life, is here, as well as a detailed list of officers of the Crown made in 1553. Most evocatively though from this time, an age of realpolitik mixed with magic, is a map with information about the wax effigies found in 1578 intending harm to Elizabeth I. The Society is to be congratulated on its efforts to share its extraordinary collections not only with generous loans to exhibitions elsewhere but at the heart of the Society itself.

‘Blood Royal: Picturing the Tudor Monarchy’ is at the Society of Antiquaries of London, until 25 August, 2017.