Retrospectively, what is perhaps most striking about Kerry James Marshall’s exhibition at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies is the range of media used. Paintings, films, animations, sculptures, photographs and installations have been brought together in a stimulating and thought-provoking show which, somewhat against the odds, manages to cohere.

Believed to be a Portrait of David Walker (circa 1830) (2009), Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the Deighton Collection, London

The exhibition opens with a painted portrait titled Believed to be a Portrait of David Walker (circa 1830) (2009). The work depicts David Walker, an African-American abolitionist famous for the pamphlet ‘Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World’ (1829), which urged slaves to revolt and fight for their freedom.

Employing a format typically used in the 19th century to depict white bourgeois men, Believed to be a Portrait of David Walker (circa 1830) functions as a kind of imaginary commemoration, an attempt to fill what Marshall has described as the ‘lack in the image bank’. At the same time, the way in which the figure has been painted – the face a shiny bluish-black, the background indigo, the figure’s jacket a dusty blue – has an abstracting effect that works to undo the painting’s referential function. The histories of paint and colour are as much the subject of Marshall’s work as David Walker is.

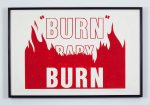

Scattered across the floor of the exhibition’s main room are comically oversized stamps and ink pads, as well as posters whose slogans are drawn from the civil rights movement: ‘BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL’, ‘BLACK POWER’, ‘BURN BABY BURN’, and so on. (The oversized stamps seem to have been used to produce these images). There is a subdued but carnivalesque quality to these posters, one that is also encountered in other works like Black Star (2011) and The Art of Hanging Pictures (2002).

Black Star (2011), Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of Marilyn and Larry Fields, Chicago.

The first work is a painting of a black woman bursting out of a painted star, a comment perhaps on gender stereotypes. The second work comprises variously sized photographs that have been hung in a haphazard manner. These depict, for example, a series of churches, a fenced sports field, a kitsch pink plastic swan or a worried-looking African-American mother. The work might be understood to emphasise the imbalanced nature of black experience, while at the same time offering a humorous commentary on the supposed neutrality of picture hanging.

The second part of ‘Painting and Other Stuff’comprises a more specific examination of black visual culture. After a series of cartoons in which figures in a museum discuss the imposition of Western European models of culture, the viewer is met with a short film of an African-American woman examining items in her home. In each scene African folk art and voodoo enter into an uneasy dialogue with Christian religious icons. Similar issues are addressed in Gleaning: An Image Reclamation Project (2003). The work comprises an ever-expanding image bank of clippings from popular magazines and art history books. These explore the commodification of ‘blackness’, the cultural stereotypes that define the African-American subject, as well as the problematic quality (and general absence) of representations of black subjects in the art-historical canon.

It would be difficult to do justice to the many works in the show, both because of their differences and because of their complexity. Whether they address the history of slavery, race politics, black power or social emancipation, Marshall’s works do not lend themselves to simple interpretations. What they offer are ambiguous, often conflicting views on the historical position of the African-American subject, all the while exploring and critiquing the ideological underpinnings of visual culture and the history of art.

‘Kerry James Marshall: Painting and Other Stuff’ is at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, until 26 October.