Walking into an exhibition titled ‘The Renaissance Nude’, you might expect to be assailed with flesh. The fact that you are not initially feels a bit of a let-down; yet it’s also refreshing. Instead, the exhibition shows intimate and, on the whole, small-scale studies from across a range of media – paintings, drawings, woodcuts, manuscripts, statues – presenting the nude in a range of ways. Nudes in the 15th and 16th centuries were produced for churches and monasteries, private collections, and anatomical treatises, while pornographic prints circulated widely. Some are full of erotic possibilities, though a remarkable number are distinctly unerotic: ironically the least sexy objects are the ones that verge on pornography.

The rediscovery of classical art and philosophy – and in particular the excavation at the beginning of the 16th century of the Roman sculptures Laocoön and his Sons and the Apollo Belvedere – had a major effect on how human nakedness was brought into art. Depictions of this kind were new, and shocking, and Christian connotations of the nude were conflicted, as it signified both the perceived sinfulness of the naked body and the vulnerability and suffering of saintly bodies. This is not to say that the exhibition is lacking voluptuous Venuses. An early Titian, Venus Rising from the Sea (‘Venus Anadyomene’) (c. 1520), is a stunning example. The painting captures the moment after her birth, the same scene as in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, only with downsized scallop shell. She emerges amid soft textures of sea and sky, wringing out her hair, entirely self-absorbed. She is not Botticelli’s Venus, framed for the viewer: we are glimpsing a private moment.

Venus Rising from the Sea (‘Venus Anadyomene’) (c. 1520), Titian. National Galleries of Scotland

Another depiction of the goddess hanging nearby, an engraving by Dürer, gives a very different interpretation. The Dream of the Doctor (c. 1497) presents a sleeping scholar unaware of the naked goddess standing, almost pressing, against him. Rather than a figure of serene classical beauty, this Venus is a demonic medieval temptress, demonstrating how Renaissance ideas still sat uneasily in relation to the world they were replacing. The exhibition catalogue alerts us to a ring on Venus’s left hand, suggesting that this is an allusion to ‘a number of medieval legends of men who had become enthralled with statues of the naked goddess and who – heedless of the idolatry of such an act – had pledged love or marriage to her, placing a ring on the statue’s finger’.

Elsewhere, an exquisite statuette (1497) in silver and gilt, which may have been designed by Hans Holbein the Elder, depicts Saint Sebastian chained to a tree, with arrows through his calf and torso. His expression is one of tranquil, almost Christ-like, suffering. The eye is drawn to individual details: the gentle curls of his hair, the veins in his arms, and, through a crystal window on the statue’s base, small fragments of wood that were reputed to be a relic from one of the arrows that pierced the saint’s skin. Created for a monastery, this work could instruct the monks on the sacrifices their faith demanded. In contrast to this, Cima da Conegliano’s painted interpretation of the saint (1500-02), which hangs close by, presents an ethereal Sebastian standing almost unperturbed, with a single arrow protruding from his thigh. But the arrow seems almost incidental: indeed, his insouciant pose finds an echo in the next room, where Perugino depicts Apollo listening to Daphnis playing his pipe (c. 1495). The former was painted as an altarpiece for the Chiesa di San Rocco in Venice, and one can imagine the congregation admiring the sublimity of his Christian faith.

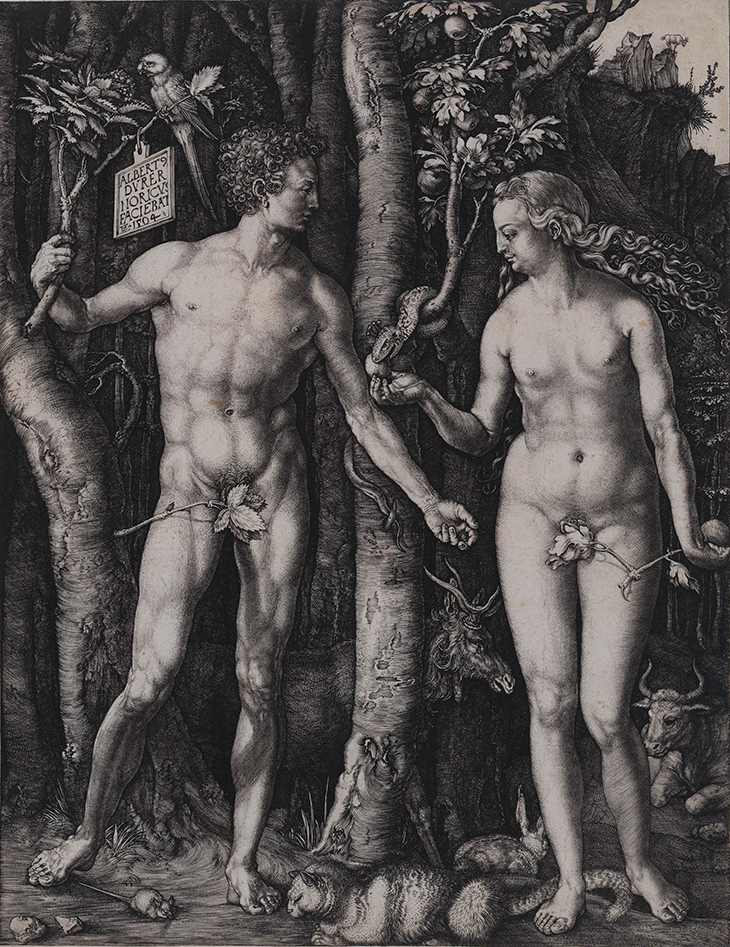

Adam and Eve (1504), Albrecht Dürer. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Other bodies here are sinful, and vulnerable. Dürer’s Adam and Eve (1504) seem ashamed of their nakedness even before their fall, covering themselves with fig leaves while holding unbitten apples, and Dieric Bouts’ Way to Paradise (1468–69) has partially clad men and women ascending to heaven alongside naked figures experiencing the torments of hell. Even more arresting are the displays of naked bodies perpetrating and subjected to violence: an Antonio Pollaiuolo engraving, Battle of the Nudes (1470s), a painting of Saint Barbara’s Escape from her Father (1430–35), attributed to Konrad von Vechta, and The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand from the workshop of Hans Leu the Elder (1508–09). Meanwhile, Pollaiuolo’s bronze statue, Hercules and Antaeus (c. 1470s), is nothing short of sexy in its portrayal of the two enemies in the midst of combat.

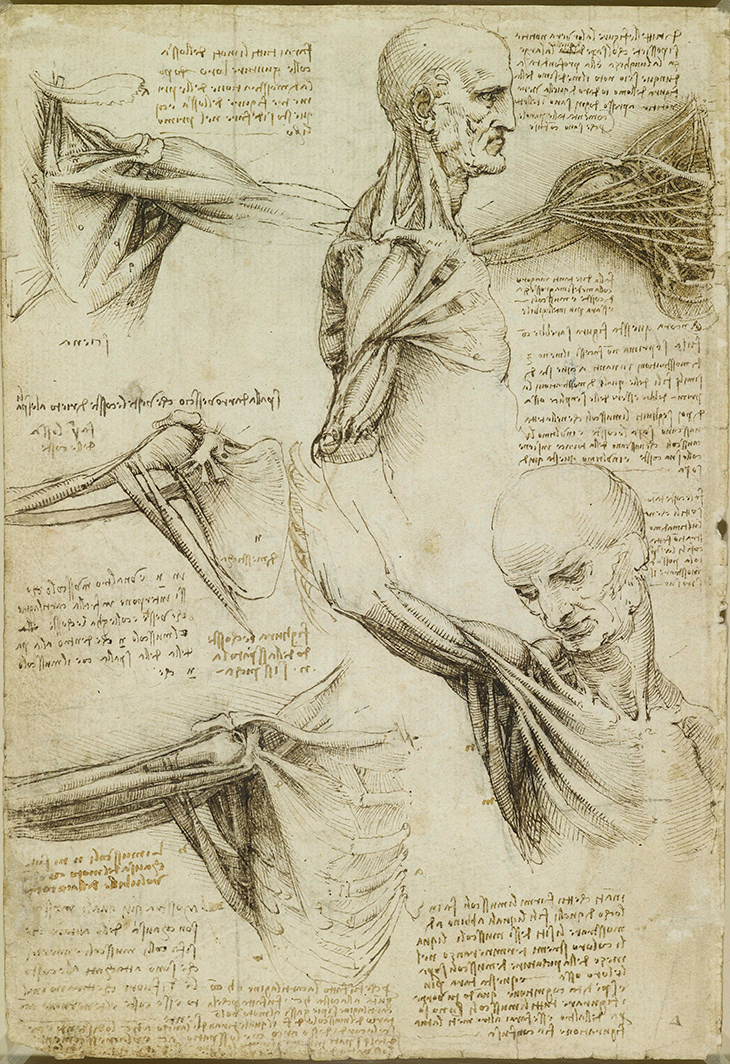

The Anatomy of the Shoulder and Neck (verso; c. 1510–11), Leonardo da Vinci. Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The close link between artistic depictions of the nude and the burgeoning anatomical science provides a further dimension to the exhibition, with an extraordinary Leonardo sketch of the sinews of a human shoulder (1510–11), and an early printing of Dürer’s Four Books on the Proportions of the Human Body (1528). Throughout the exhibition, then, we see differing views of nudity competing and cohabiting. It is particularly interesting that the curators opted against any geographical or chronological differentiation between the pieces. Rather, the works are divided thematically, except for the final room, which reconstructs aspects of Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua’s, collection. D’Este was the first female art collector of the Renaissance, and inaugurated the great Gonzaga collection (a nod back to last year’s ‘Charles I: King and Collector’ exhibition at the Royal Academy, as the Gonzaga collection was purchased by the monarch in 1628).

The virtue of this approach is that we encounter northern and southern European artists side by side, and see how differently art was developing in these regions, even – and perhaps especially – when the same subject has been chosen. Even before the Reformation, the northern European artists seemed far more austere in their distrust of the human body, while their Italian counterparts delight in it, both as sensual and celestial. By placing works from across Europe and the years 1400–1530 alongside one another, the exhibition highlights both ruptures and continuities in a period best known for epochal change – and shows the Renaissance nude to be far more multifaceted than one might have previously imagined.

‘The Renaissance Nude’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 2 June.