In 1567 John Brayne, a young Londoner recently made a Freeman of the Grocers’ Company, had embarked on building a structure in Whitechapel known as the Red Lion. This east London venue was to have a ‘stage for enterludes or playes’, and was to be ready for ‘the playe which is called the storye of Sampson’ (the authorship and text have been lost) to be performed there on 8 July 1567. This building, the remains of which archaeologists from University College London believe they have found at a site formerly occupied by a self-storage facility, is recognised as the earliest known purpose-built ‘public’ playhouse of the Elizabethan period.

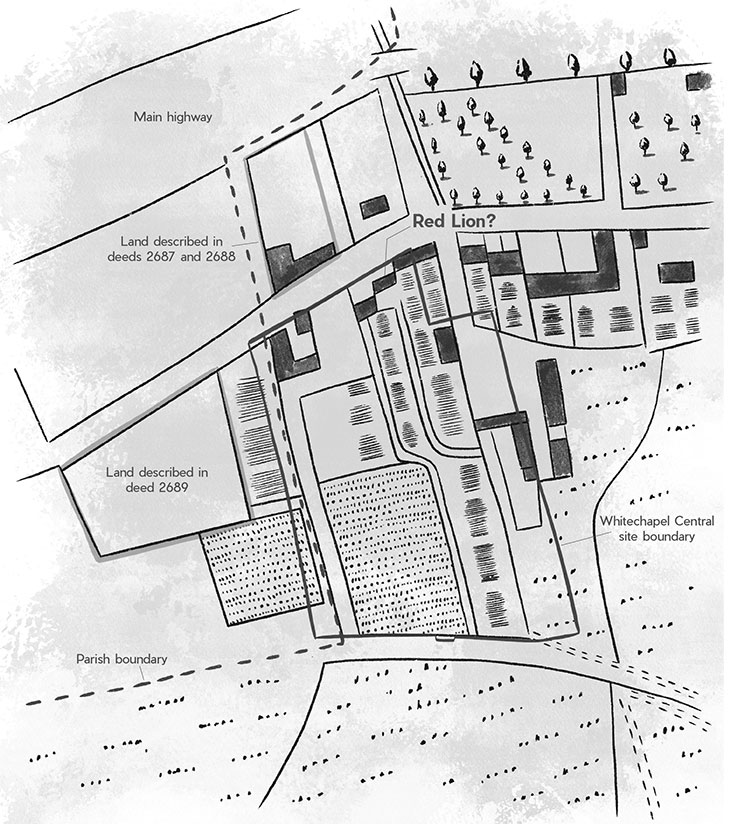

Excavation area and probable location of Red Lion based on Gasgoyne Map (1703) and historical land deeds

The plague, a recurrent theme in the history of London, had been particularly bad in 1563. It was thought to have been exacerbated by the profusion of performances and players in the city. In 1565, the city’s aldermen were instructed not to permit ‘any plays or enterludes in any tavern, inn, victualling house or other place within any of their said wards’. There might have been some sense, therefore, in establishing such a place outside the city walls. Mile End Green was a small hamlet surrounded by fields, with alehouses and fairs already popular with City revellers. The playhouse was to be situated there, within the ‘court or yard lying on the south side of the garden belonging to the […] farmhouse called […] the Red Lion’. This farmhouse likely already had a history of providing refreshments and entertainments in the area, which would have made the creation of a playhouse there an attractive idea.

Moreover there were theatrical antecedents in that location, all probably open-air. In August 1501 Henry VII authorised payment of three shillings and fourpence (about 20 pence today) ‘for the pleyers at Myles Ende’, and in May 1539 ‘a great muster was made by the citizens at the Mile’s end, all in bright harness, with coats of white silk, or cloth and chains of gold, in three great battles’. A large feast took place there on March 1559, prepared by the royal cooks, followed by an elaborate military show, archery, dancing, bear-baiting and other displays in the recently crowned Elizabeth I’s presence. Years later in Henry IV Shakespeare paid homage to amateur theatricals such as ‘Arthur’s Show’ in which Justice Shallow, remembering his youth, said he played Sir Dagonet the fool ‘at Mile-end Green’.

With a site in mind, Brayne may have interested his brother-in-law James Burbage – joiner, actor and later theatre impresario (and father to Richard Burbage, Shakespeare’s friend and principal actor). It has been speculated that Burbage’s acting career, with the Earl of Leicester’s Company, had already taken off by this date and that it was he who encouraged Brayne to build a playhouse. Nine years after the building of the Red Lion, the pair built the polygonal Theatre in Shoreditch, a more permanent – and successful – theatrical venue, which staged some of the early Shakespeare plays until 1598, when it was dismantled and its timbers reused for the Globe on the other side of the Thames. (Burbage, however, bullied and cheated Brayne, who lost out financially over the project.)

A 3D model rendering of the Red Lion stage

Our knowledge of the Red Lion has been largely based on two lawsuits in 1567 and 1569, concerning its construction. Brayne employed two carpenters to build elements of the venue: William Sylvester to construct the galleries, and John Reynolds the stage, but he found fault with both carpenters, this despite the fact that the stage and galleries were finished before the Samson play was booked for the July date.

From what we learn from these legal records, the stage dimensions reveal it to be larger than many of its successors: 1.5m above the ground, 12.2m in length north to south and 9.1m east to west. It was also to have ‘a certain space or void part of the same stage left unboarded in such convenient place’, which suggests a trapdoor – an early indication of staging potential.

The excavations revealed a rectangular ‘ensemble’, 30m east to west by 15m north to south, with the stage occupying the eastern side. There was evidence of walls to north and south but without proper scaffolds there. The western part, however, does appear to have had two rows of substantial timbers. This suggests the footprint of an upper gallery for seating or standing, as in the early bear gardens, some 12m back from the front of the stage, leaving a large standing area or ‘yard’ at ground level (familiar to us from later playhouses). The excavation also found everyday bits and pieces: ceramic money boxes, coins, and other detritus – all of which suggest an audience.

Archaeologists excavating the timber structure

There is no documentary or archaeological evidence that anything much happened at the Red Lion for 30 odd years after the events of 1567. It is conceivable therefore that the building might have hosted plays or any other entertainments. However, in the early years of the 17th century there is archaeological evidence that the Red Lion was refurbished, with scaffolds reworked and strengthened. It appears that the building was repurposed as an animal-baiting arena or bear garden: nearby were six dog burials, whose canine occupants displayed filed-down teeth and skull wounds. (Purpose-built polygonal or circular ‘bear gardens’ were popular in London and beyond between the 1540s and 1660s. The Hope playhouse, built in 1613, was a dual-purpose venue hosting drama for half the week and animal-baiting the other half.) The Red Lion farm was also restored at this time, and became a more formal inn, which perhaps accounts for such finds as a large, late 17th-century tavern mug decorated with a royalist medallion of Charles II.

Royalist-medallion tavern mug

John Brayne, who might be called the father of the London playhouses, died in 1586 and was buried in Whitechapel’s St Mary Matfelon (along with his wife and a number of local players), now the site of Altab Ali Park. The nine London playhouses that came after the Red Lion were different shapes and sizes, including one square, and two were converted from houses, two more from inns. Though not an exact physical phototype for later London playhouses, Brayne’s Red Lion was certainly what you might call a dress rehearsal. The archaeologists from University College London must be congratulated for their excellent contribution to theatrical history.

Julian Bowsher is a Senior Specialist at the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) and the author of a number of books and articles on Shakespeare’s playhouses, including Shakespeare’s London Theatreland: Archaeology, History and Drama.