From the January 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Few film-makers have left their mark upon the medium on quite such a grand scale as Ray Harryhausen (1920–2013). Over the course of a remarkable career, Harryhausen extended the technical possibilities of cinema and the visual language of science-fiction and fantasy film. Having honed his stop-motion work on early Cold War creature features such as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), he went on to create the relentless skeleton warriors of Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and the giant mythological monstrosities of Clash of the Titans (1981), the last of the grand pre-CGI spectacles. ‘Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema’ at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art offers a unique glimpse into film history through the animator’s extensive archive of source material, sketches, models and test footage. One exhibit – a poster for the first Lord of the Rings film – bears an inscription from the director Peter Jackson: ‘The Lord of the Rings is a “Son of Harryhausen”!’ From Star Wars and Jurassic Park to Jackson’s own fantasy epics, Hollywood cinema has been populated for half a century or more by ‘Sons of Harryhausen’.

Medusa model from Clash of the Titans (c. 1979), Ray Harryhausen. Photo: Sam Drake (National Galleries of Scotland); © The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation

Harryhausen learned his craft largely from the special-effects pioneer Willis O’Brien, whose work on King Kong (1933) inspired the teenager who would become his most famous assistant and protégé. The first room of the exhibition – presided over by a back-projected image of the giant Kong – is duly devoted to O’Brien, his innovative animation techniques, and his art style, which was heavily influenced by the illustrations of Gustave Doré. This is a good place to begin not only because it tells the story of Harryhausen’s introduction to the possibilities of cinematic art, but also because, by demonstrating the state of the art in 1933, it sets the scene for an exhibition that traces the transformative advances of the Harryhausen era in film animation. On the other side of a temporary partition, a collection of intriguing juvenilia features a home-made King Kong marionette, representing Harryhausen’s earliest efforts as a teenage model-maker. This first section of the exhibition ends in the Gabrielle Keiller library, where personal effects including Harryhausen’s art materials and his Academy Award are displayed alongside an array of sketches and source materials. The library – which permanently houses the collections of Keiller and Roland Penrose, fellow collector of Surrealist art – is a fitting context for displaying these images in which cowboys duel with dinosaurs and extraterrestrial dragons leer menacingly at 1950s rocket-ships.

Original skeleton models from Jason and the Argonauts (c. 1962), Ray Harryhausen (armature by Fred Harryhausen). Photo: Sam Drake (National Galleries of Scotland); © The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation

As the exhibition moves upstairs, chronology becomes less significant and objects from across Harryhausen’s career begin to appear in close proximity. Among the most intriguing of these are the designs and models for the many intricately articulated figures brought to life in the great mid-career films: Cyclops from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), the colossal statue Talos and the seven-headed Hydra from Jason and the Argonauts, and the still remarkably lifelike skeletons which were to become a recurring Harryhausen motif. The design drawings demonstrate how Harryhausen was able to deploy his knowledge of anatomy, both human and animal, to create extraordinarily realistic motion. The carefully constructed figures displayed here are the result of a remarkable combination of imaginative freedom and precision engineering. Similarly, the many preparatory sketches and overpainted location photographs collected in the exhibition’s middle rooms are clearly the work of an artist willing to experiment repeatedly with new and varied media in pursuit of a single aim: to astonish moviegoers. One highlight is a large-scale reconstruction of the technique of ‘Dynamation’, a novel form of stop-motion animation which worked by layering and refilming background, middle ground, and foreground to produce a convincing composite image. Through this proprietary technique, Harryhausen was able to incorporate his articulated miniatures into full-scale three-dimensional scenes.

Armature of Cyclops from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1957), Ray Harryhausen. Photo: Sam Drake (National Galleries of Scotland); © The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation

The final rooms explore Harryhausen’s influence on later film-makers. This is perhaps the least fully realised part of the exhibition, relying on a specially produced 15-minute documentary (also available on the exhibition’s website), a clever zoetrope installation by the contemporary artist Eleanor Stewart, which lovingly animates several Harryhausen creatures, and a placard tracing the debt owed to Harryhausen by numerous contemporary film-makers – from Steven Spielberg to emerging talents such as the Japanese animator Ru Kuwahata and the Bafta award-winning Daisy Jacobs. Finally, those who want to test their mettle against gorgons, colossi and skeletons can try out a digital ‘animation studio’ in which exhibition-goers project their own images into a Harryhausen-esque movie scene. On Halloween, when I visited, a troupe of costumed Edinburgh locals were putting the equipment to terrifying use.

The captioning throughout is generally helpful, if a little basic, and helps to ground each object in the context of Harryhausen’s work and of the cinematic era to which it belongs. There are some amusing details – such as the information that the shell used to create a giant crab for Mysterious Island (1961) ‘was bought by Harryhausen in Harrods’ – but also stern words for the ‘regressive stereotypes’ on display in Sinbad’s exotic adventures, as well as for the sexism that reduces most women in these movies to either femmes fatales or damsels in distress. Understandably, the curators have felt obliged to contextualise the more lurid excesses of the period’s cinema, but this might have been used as an opportunity to go beyond reflexive disclaimer by acknowledging the work of Harryhausen’s less celebrated predecessors and contemporaries. These content warnings come across as merely dutiful, whereas a more positive emphasis might have been put on the work of female stop-motion innovators such as Helena Smith Dayton or Lotte Reiniger, both early masters of the medium. That would have been appropriate, given Harryhausen’s own emphasis on film animation as a developing and experimental art form and his reverence for the work of prior artists. That omission aside, the exhibition succeeds in offering visitors access to a unique and rich archive of special-effects history. Focusing on a series of extraordinary cinematic achievements rather than a single organising narrative, it depicts its subject as both a painstaking craftsman and a hugely talented multimedia artist.

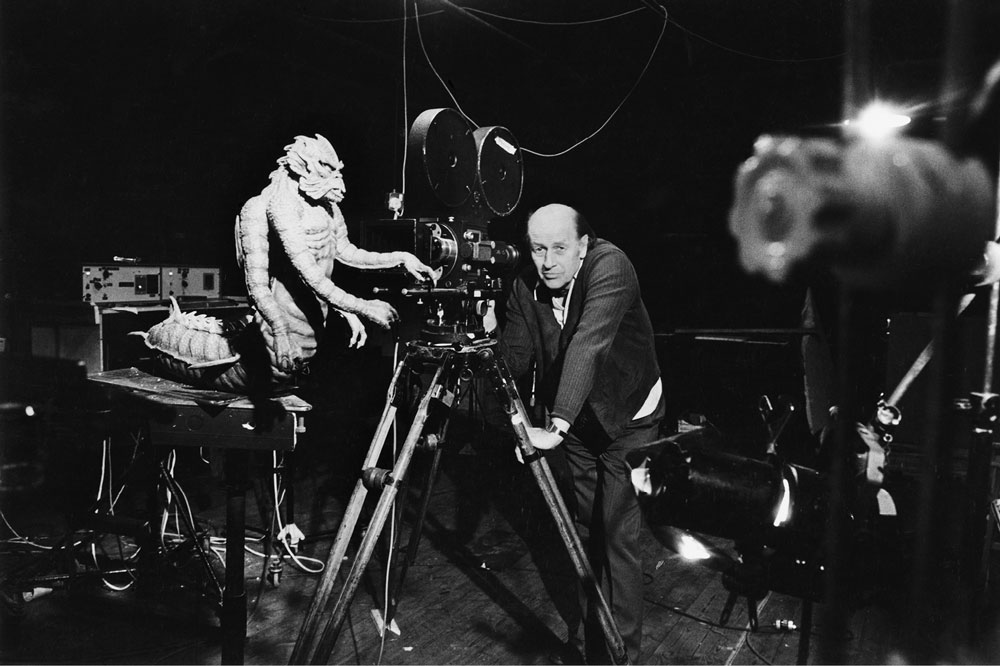

Ray Harryhausen on set with a model of the Kraken from Clash of the Titans (c. 1980). © The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two), Edinburgh, is temporarily closed to the public due to Covid-19 restrictions. For more information on ‘Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema’ (scheduled to run until 5 September) visit the institution’s website.

From the January 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.