‘Is that it? Are you sure?’ Those were Prince Philip’s first words to me when, at his first sitting for a portrait I’d been commissioned to paint of him in 2006, he set eyes on my painting equipment: a small canvas, no more than 12 by 15 inches, perched on my travel easel in a grand room at Buckingham Palace. The painting was to be a series of three works for a charity, Muscular Dystrophy UK, which the prince had been a patron of for many decades. The other portraits were of Richard Attenborough and an esteemed scientist, but for me this one turned out to be the most powerful: partly because Prince Philip gave me a bit of time, perhaps four sittings of an hour or an hour and a half. Getting to know someone a bit is crucial for good portraiture.

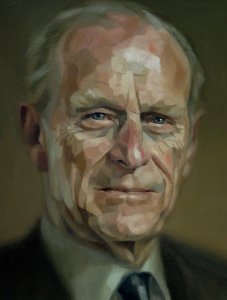

I’d decided to make a small painting focusing only on Prince Philip’s face. It probably did look a bit ridiculous, setting up my diminutive canvas in a vast, heavily gilded room in which the royals always sit for portraits (there were two large, unfinished works by other artists facing the wall). But at that time the Duke of Edinburgh was increasingly seen as a figure of caricature, and I felt that recent portraits of him had picked up on that mood. I was determined to paint what I saw. In the long term portraits only really have value if they’re truthful. there’s no point mocking – or flattering – anyone unnecessarily: those things lose currency over time.

Jonathan Yeo’s portrait of Prince Philip from 2006. Courtesy the artist

During the sittings we were mostly left alone, as far as I remember, with an equerry outside the door. Portrait sittings work best when it’s just you and the sitter. Was he a patient sitter? He was an alpha male, for sure, someone with a fierce intelligence who was easily bored – but he couldn’t just walk away from a portrait sitting as he might have done at a cocktail party. He barked things out that he thought were funny – and often they were very funny – or just for the sake of filling the silence. But our conversation ranged widely, across science, history and foreign affairs. As the sittings went on he started to throw curveballs at me, as though he were trying to provoke me into taking positions he could argue against it. During the second or third sitting, once he’d got the measure of me, he asked what I thought about the war in Afghanistan. ‘I don’t know, what do you think?’, I said. ‘No, no,’ he said, ‘I asked you first.’ He really wanted me to spar with him – not the easiest thing to do with the prince consort when you’re trying paint his portrait. For me the whole experience was a juggling act.

The prince asked a lot of questions about my painting process as the sittings went on. ‘Why are you using that paint now?’, ‘What’s in that jar?’ and so on. The questions became more and more precise, so eventually I asked him if he had ever tried painting himself. ‘Oh yes,’ he said. ‘I did used to, and I’m glad you asked me, because I’ve actually taken it up again recently.’ Then he said something that, as a professional artist, I dread to hear: ‘I’d love to show you some of them and hear what you think.’

I hoped he’d forget about it – and before the next sitting I was quite nervous about what I’d say. He wasn’t the type of person you could just placate with some airy platitudinous waffle. But sure enough, at the next sitting, he had the pictures – and I quietly panicked. Knowing by that point that he didn’t suffer fools, what would I say? But when he pulled them out, they were nothing like what I’d been expecting. I was hugely relieved: they were the work of a good amateur painter, with lovely colours, executed in the style of early 20th-century French painting, a Bonnard, a bit Vuillard. They weren’t angry or powerful, but rather subtle and slightly Romantic. Some were Gauguinesque paintings of South Sea islanders, images from his time in the navy, then there was one painting of the Queen across the room having breakfast, and recent landscapes, views from the windows at Sandringham I think.

It turned out my worry was unnecessary. He didn’t actually ask whether I liked them but instead whether I had any tips for how to paint certain things better. That seemed representative of the character I saw overall: far less interested in reflecting on what others thought of him than how to solve problems and move on. Practical not emotional.

When I look at my portrait of Prince Philip 15 years on, what I see is a painting of a man with a restless intellect. He could be about to say something funny or provocative, or something very perceptive. He’s certainly about to say something. He struck me as a person who it would be great to know quite well – and difficult to know very well or to live with. Hopefully that comes across in the painting.

I didn’t ask what he thought of the portrait. It’s protocol, I think, that royals don’t comment on their portraits, plus I’ve learnt over the years that the immediate reaction of a portrait’s subject has little connection with its wider or longterm success. I heard later that other members of the royal family liked it – and it’s much more reassuring to know that people who really know the sitter feel that you’ve got it right. Prince Philip did come and look at it at the end of the final sitting. He smiled, but didn’t say anything.