We are now counting down to the opening of the Venice Biennale, when the focus shifts to the vernissage and the unveiling of artworks and exhibitions. As Commissioner of the British Pavilion, however, my work began back in February 2016, when the selection committee was convened to choose the artist to represent Britain in 2017. This is a group of respected individuals from all factions of the UK’s arts sector; its members change for every Biennale and are drawn from all corners of the UK.

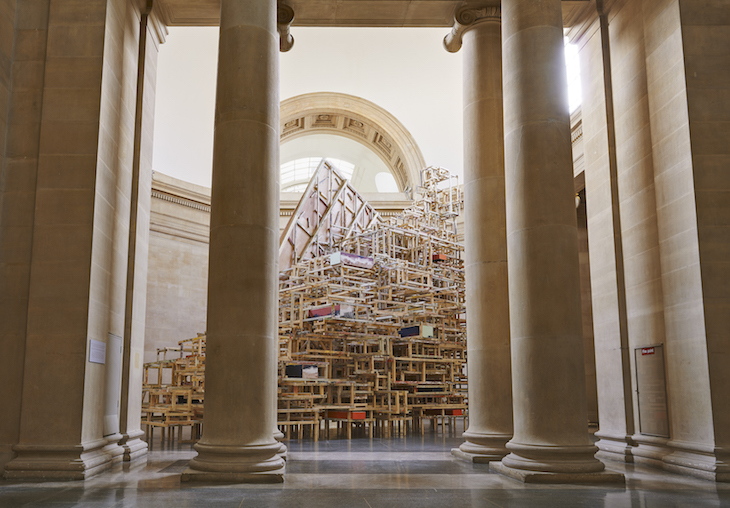

Installation view of Phyllida Barlow’s dock (2014) in the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain, London. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Phyllida Barlow

There was a strong consensus from the panel members in favour of Phyllida Barlow, an artist who they felt would take an ambitious approach to the commission and who has, deservedly, enjoyed a lot of exposure recently. Throughout her career, Barlow has used cheap, readily available materials, such as timber, concrete and fabric to make sculpture, exploring in the process the limits of what is possible with those materials, and often using them to create colossal and immersive sculptural ensembles. It fell to me to invite Phyllida and she responded positively, with gratitude and enthusiasm. It’s great to be able to offer an artist such an exceptional opportunity, without their having to apply for it or be part of a competition.

A fantastic group of people at the British Council work together with the artist and their team to make the exhibition happen. As well as this, the British Council is responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of the British Pavilion itself – a listed building from 1887. This year – which is the 80th anniversary of the British Council’s assuming responsibility for exhibitions in the British Pavilion – we’ve successfully launched a patrons scheme, which allows individuals to make donations in support of the project.

The British Pavilion in Venice. Photo: John Riddy; copyright British Council

The genesis of the exhibition is marked by certain key moments. During the first visit to Venice in March 2016, Phyllida was particularly impressed by the height of the main gallery in the British Pavilion. The building is like the tardis: as you enter, the doors don’t seem that large but the ceiling in the first room is more than ten metres high, and the somatic effect is really exhilarating.

Last May, at Phyllida’s London studio, we discussed drawings and models and talked through possibilities and limitations. During a further site visit in July, members of the Biennale team explained the various procedures necessary to get permission for works outside the Pavilion. Phyllida’s working process is one of continual revision and reassessment, as ideas coalesce and then morph into something else. Some elements that seemed quite fixed and determined disappeared, or reappeared later on in another guise! Right up until the last weeks, Phyllida was revising and reshaping her plans. Indeed that process continued during the installation in the Pavilion when certain decisions and adaptations were made in the moment, in situ.

Later in the year, when work was well underway, I visited Phyllida’s studio again and it was possible to see elements of the finished work emerging – albeit in sections, since the works were meticulously planned to be reassembled on site. Now that I’ve seen the final work, I can say that it is stunningly beautiful, but also melancholic. Perhaps there’s a Death in Venice influence there – Phyllida certainly referred to Luchino Visconti in our conversations.

From the beginning Phyllida talked about Venice, musing on it as a spectacle, about its focus on façades, about mirroring, and reflections from the lagoon, and the city’s unreality. She was also very conscious of the nature of the Biennale, particularly its national pavilions: thinking about what that means today, and what it means to be showing in the British Pavilion at this point in history.

As I write, I’ve just returned from watching the last days of the install in the Pavilion and I’m amazed that this ambitious show has been completed in just one year. Phyllida’s work often has a spine-tingling force: here, it has a dramatic effect on the body when you’re in the space with it. As I explored the show, I felt like Alice in Wonderland wandering around in a strange and curious environment.

The arts are a powerful tool for breaking down barriers: now more than ever we need to embrace international dialogue, working and collaborating together; the Venice Biennale offers a unique opportunity to achieve this. By exhibiting at the British Pavilion, Phyllida Barlow joins a conversation with numerous other artists across the whole Biennale, their collective voices giving us a powerful sense of current concerns and practice. She also joins the roster of exceptional artists who have exhibited at the British Pavilion since 1909. The British Pavilion is an important place for people to meet, gather and congregate: we want to welcome the world to the Pavilion, show what Phyllida has done and have as many conversations as possible.

Phyllida Barlow’s British Council commission is at Biennale Arte 2017 from 13 May–26 November.

From the May issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.