‘On Thursday morning, August 25, 1994, I entered the Rubavu Refugee Camp near Gysenyi in Rwanda as school was about to begin.’ These words, written by Alfredo Jaar, have been laser-cut in a small, sans-serif type into a false wall dividing the lower-ground level at the Goodman Gallery in Mayfair. From behind the partition light streams through the words. ‘As I approached the make-shift school, children gathered around me. I smiled at them and some smiled back. Three children, Nduwayezu, Dusabe and Umotoni, were seated on the steps in front of the school door. Nduwayezu, five, the oldest of the three, was the only one that looked directly at my camera.’

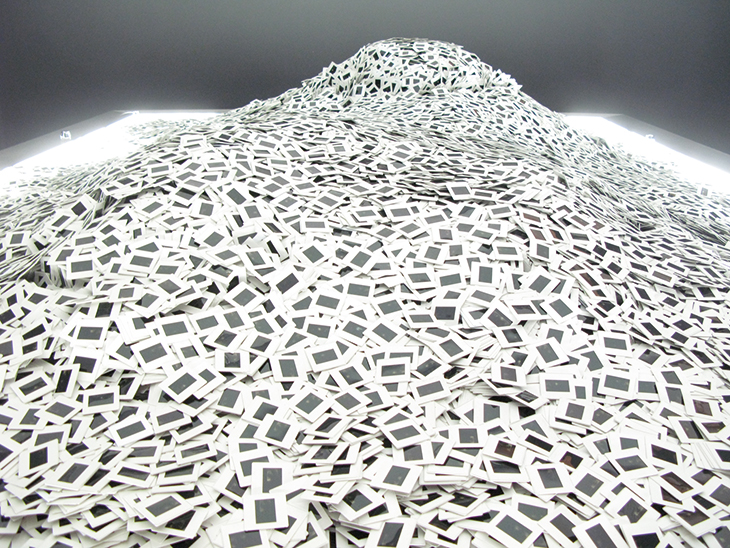

Nduwayezu was one of countless children orphaned by the Hutu-led genocide of 1994, a massacre thought to have ended somewhere between 500,000 and a million lives. Arriving at Rubavu not long before Jaar’s visit, Nduwayezu, one of 37 such orphans at the camp, wouldn’t say a word. He remained mute for four full weeks. ‘I remember his eyes,’ Jaar’s text continues. ‘And I will never forget his silence.’ Behind the partition, a table 18-foot long and 12-foot wide is piled high with a million photographic slides. Each slide is identical: the eyes of Nduwayezu staring back at us, the eyes that met Jaar’s camera lens in 1994 and that have haunted him ever since.

The muteness referred to in the work’s title, The Silence of Nduwayezu (1997), also represents for Jaar the ‘silence of the international community’. Despite being in possession of intelligence reports about the genocide weeks before it reached its peak, the Clinton administration failed to intervene in Rwanda and the United Nations was kept on the sidelines. As another of Jaar’s works makes clear, for 16 weeks between April and July 1994, while bodies piled up in Rwanda, Newsweek magazine reported on strategies for navigating a bear market, the presumed health-giving properties of phytochemical supplements, and a planned mission to Mars, apparently finding nothing worth reporting about in the mountains and savannas of the small landlocked republic in central Africa. Untitled (Newsweek) (1994) consists of a line of framed magazine covers spelling out this willed blindness. ‘Nduwayezu saw what we refused to see,’ Jaar concludes ruefully as we go around the Goodman Gallery before the opening of his exhibition there in November 2019.

Installation view of ‘The Silence of Nduwayezu’ (1997), Alfredo Jaar. Image courtesy Alfredo Jaar and Goodman Gallery, London, Johannesburg, Cape Town; © the artist

Jaar considers that his work can still be divided into two halves: ‘before and after Rwanda’. The experience fundamentally changed his relationship with images. ‘I was working with the same kind of images that photo reporters took in Rwanda,’ he tells me. ‘And I never felt that my images would make any difference. […] That’s why I adopted a different kind of strategy.’ There’s a certain irony in the fact that in March of this year, Jaar became the 40th recipient of the prestigious Hasselblad Foundation prize, which recognises ‘pioneering achievements in photographic art’, with past winners including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka and Nan Goldin. What does it mean to recognise an artist whose practice has long revolved around a questioning of that photographic art, a critical suspicion of its efficacy and a teasing of its limits? For, whether through photographic images, text or built installations, Jaar requires viewers to go beyond mere looking.

‘I’ve had a critical position regarding photography,’ Jaar tells me when I speak to him by Skype in April. ‘I respect photography enormously, but I’m more concerned with what I call the politics of images. I’m interested in deconstructing photography and the way it influences us in the world.’ This ‘in the world’ is crucial – for Jaar, no image exists in isolation. His post-Rwanda work has consistently asked the viewer to confront the image as a node in a network of powerful forces and historical events. His assemblages of magazine covers – such as both the aforementioned Untitled (Newsweek) and From Time to Time (2006), in which a grid of nine issues of Time magazine lays bare the colonial construction of Africa in Western eyes – ask us to question the myths perpetuated by the media and consider the truths they conceal. The Sound of Silence (2006) is an installation that starts with a celebrated photograph – Kevin Carter’s Pulitzer-winning shot of a famine-stricken Sudanese infant – and invites the viewer to enter a built structure and watch the eight-minute video showing within. The work pulls the image apart, eking out its context, and shaping the experience of it through time.

When an earlier version of The Silence of Nduwayezu was first exhibited at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra in 1996, Jaar noticed something rather strange about the way museum-goers were behaving around it. One day a guard showed him the CCTV footage and there it was, plain as day. People would approach the table, pick up one slide or another to look more closely, and then, as soon as they thought no-one was watching, they would quickly slip it into their pocket and walk away. Jaar’s response to these apparent repeated acts of larceny was typically philosophical. ‘They were not stealing,’ he insists. ‘It was a way for them to feel connected to this story.’ He instructed the guard to look the other way, turn a blind eye and let the theft continue ‘– but of course,’ I added, ‘“Don’t encourage them!”’

Born in Santiago in 1956, Jaar came of age just after Augusto Pinochet’s military junta came to power. An early work consists of a calendar for the year 1973 in which the date for every day after 11 September, the day Pinochet’s forces violently overthrew the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende, had been replaced by an ‘11’. ‘Every day became 11 September,’ Jaar explains. ‘It was a nightmare from which we never woke up.’

At university he studied architecture as well as film, but he was never a conventional designer of buildings. After five years of study, he became the first person to graduate from the architecture course not with a blueprint or model for a building to show for it, but a poem. Words continue to hold a powerful place in his work, and to this day you will find quotations from Samuel Beckett or Anna Akhmatova peppering his light boxes and video works. But he continues to think of himself as ‘an architect who makes art’. Most of his closest friends are still architects and he maintains what he refers to as ‘a schizophrenic relationship with the art world. I have always a foot in and a foot out.’

Still from a video documenting ‘A Logo for America’ (1987) by Alfredo Jaar in Times Square, New York. Image courtesy Alfredo Jaar and Goodman Gallery, London, Johannesburg, Cape Town; © the artist

‘Being an artist in Chile taught me about subtle ways of speaking between the lines,’ he says. According to the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report of 1991, some 2,000 people were ‘disappeared’ for political reasons during the military dictatorship and around 30,000 were tortured. Among the artists of Jaar’s acquaintance at the time, he remembers two schools of thought. On the one hand, there were those who insisted that to produce any artworks under such circumstances would risk ‘normalising’ the regime. The other group – of which Jaar was a part – insisted on carrying on, making work that criticised the regime in various ways. ‘But we all had a line in our heads which we knew we could not cross – because if we did, we could be disappeared.’

When I ask him when he came closest to that line he points to a work of his called Telecomunicación from 1981, the year before he left for New York, which took as its starting point an image he had seen in a newspaper of women in Belfast banging together metal bin lids to mark the death of the hunger striker Thomas McElwee at the Maze prison. Jaar took to the streets of Santiago and laid the lids of trash cans out in lines, taking pictures of the arrangements along the pavement or on grass. If anyone asked him what he was doing, he would simply say he was a photographer and he liked these kinds of geometric shapes and patterns. But when he showed the work, he displayed the newspaper cutting from Belfast next to his photographs to make the meaning clear. ‘There was censorship,’ he says of the Pinochet regime, ‘but what is worse than that was self-censorship. But let me make clear: I refuse the cliché that everything I do is because I was born in Chile. It marked me, but I believe we are the product of all the different [kinds of] stimulus we have received.’

After moving to New York, Jaar continued to make work about the dictatorship in Chile, but increasingly found himself hitting a brick wall. ‘No one was interested,’ he recalls. Unfazed, he took a job at James Wines’ architecture firm, SITE, spending his free time observing the American art scene ‘like an anthropologist’. After five years his patience started to pay off. After he took part in the Venice Biennale in 1986 and Documenta in 1987, his work attained a newfound prominence, even notoriety, in the United States thanks to a piece of public art that soon developed a life of its own.

From 1982 to 1990, the non-profit Public Art Fund ran a series of ‘Messages to the Public’ on an 800-square-foot Spectacolor light board in Times Square. The programme commissioned artists such as Richard Prince, Jenny Holzer, and David Wojnarowicz, but none of their work had the effect of Jaar’s A Logo for America (1987). The message was clear: a simple outline of the United States overlaid with the words ‘This is Not America’. It lasted 38 seconds, sandwiched into a 20-minute loop of adverts and broadcast to millions of passers-by, every day from 8am to 11pm, for a month.

Jaar now refers to the work as a ‘semiotic protest’. Since arriving in the United States, he had been ‘shocked’, he tells me, ‘to discover that people would say “Welcome to America”, to read the word “America” every day in the daily press, and slowly I discovered that they were not talking about America the continent, the one I knew, they were talking about the US.’ Jaar’s Logo, then, was an act of defiance against this ‘erasure’ – in the context of repeated US interventions in the politics of Latin American countries, in Jaar’s own Chile as well as Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador – ‘of the rest of the continent from the map’.

Some commentators perceived the work as flat-out anti-American propaganda, others as a comment on the general seediness of Times Square at the time. In subsequent years, reproductions of its stark lines and caps-locked text appeared in school books. It made its return to a newly gentrified Times Square in 2014 at the instigation of Guggenheim curator Pablo Léon De La Barra, inaugurating a new chapter for a work now seen as a defence of immigrant communities which were under threat from the mass deportations of the Obama era. Later, it travelled to Piccadilly Circus in London and to billboards in Mexico City and Buenos Aires, before eventually making an appearance on the side of a boat circling the coast of Miami in 2018.

In the era of the Trump presidency and bright-red Make America Great Again hats, the work has taken on yet another meaning. As Jaar puts it, ‘This is not the America we want. This is not the America we think it is. Donald Trump doesn’t represent America.’ He has regarded these semantic shifts with a characteristic stoicism. ‘I have been observing it from a certain distance,’ he says, ‘amused and fascinated. But I have no control. There is nothing I can do about it.’

I Can’t Go On, I’ll Go On (2016), Alfredo Jaar. Image courtesy Alfredo Jaar and Goodman Gallery, London, Johannesburg, Cape Town; © the artist

In London, Jaar speaks animatedly about his need ‘to get out in the streets, to confront the real world’. Over the years, his projects have taken him from Rwanda to Hong Kong, Angola, Italy and Finland. In each new location, his work has grown out of the reality of each particular place in that particular time. ‘I’m not a studio artist,’ he insists. ‘I have never been able to create a single work that is a pure product of my imagination. Context is everything.’ But when I speak to Jaar five months later, he has been isolated in his New York apartment for five weeks due to the ongoing threat from the coronavirus pandemic, unable to travel and cut off from his studio, his assistants, and all his usual sources of inspiration. ‘It’s been really tough,’ he tells me. ‘My exhibitions have been postponed to an uncertain date. We don’t have really any urgency. So basically I’ve been listening to music, watching a lot of movies – and reading.’

Before our Skype conversation, Jaar emails me a short video he has made, his first completed work from isolation. Lasting just over five minutes, it consists mostly of a fixed camera pointed at a turntable playing the 1972 hit single ‘Soul Makossa’ by the Cameroonian musician Manu Dibango who died in March from Covid-19. The work, Jaar says, is ‘an exercise for me. It was a way to talk about the coronavirus but in a very indirect way, to send a signal from New York, which is the saddest city on Earth right now, and to make a homage to this great musician that I really admire.’

This latest little film is a work of mourning and remembrance, albeit one shot through with a spark of joy – provided, in this case, by the thrilling sound of Dibango’s pioneering funk beats. For all its howls of protest, the work of Alfredo Jaar remains animated by a utopian streak, the belief that art can alter perceptions and change the world, and the insistence that we continue to struggle in whatever way we can. For the last 70 seconds of his tribute to Dibango, the camera fades out from the image of his record player and is taken up by the words (from The Unnameable by Samuel Beckett) ‘I can’t go on. I’ll go on’: a neon work of the same title that Jaar first presented in 2016. ‘People tell me, Alfredo, that part [of the video] is too long. And I’m saying, no! It’s not long enough! I want to keep going! I want to dance!

From the June 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.