From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Soon after the philanthropist and aesthete Duncan Phillips (1886–1966) and his artist wife Marjorie Acker Phillips (1894–1985) founded America’s first museum of modern art in 1921, Duncan published a mission statement. He hoped that it would appear in italics in all future writings about the institution. So, in honour of the centennial of the couple’s oft-changing, still dazzling institution, I will repeat the ambitious line: The Phillips Collection is based on a definite policy of supporting many methods of seeing and painting.

Duncan announced his goals in his book of 1926, A Collection in the Making: A Survey of the Problems Involved in Collecting Pictures, Together with Brief Estimates of the Painters in the Phillips Memorial Gallery. He described the recent transformation of his family’s mansion into ‘a small, intimate museum combined with an experiment station’. It would serve as ‘a beneficent force in the community’ as well as a source of inspiration and comfort, dreamed up at ‘a time when sorrow all but overwhelmed me’, he wrote. Through a series of family tragedies he and Marjorie kept building the collection, supporting living artists, curating dozens of shows every year and supervising every administrative detail. Into the 1960s, Duncan and Marjorie could be found ‘personally greeting Gallery goers with a handshake and a few words of welcome’, the abstract painter Gene Davis recalled years later.

The exterior of The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. Courtesy The Phillips Collection

I toured the Phillipses’ former home in mid July. The mansard-roofed original headquarters was built in the 1890s, expanded in several phases from 1907 to 2006, and has become a wonderfully confusing multi-level maze with Gilded Age detail preserved. The staff, despite lockdown interruptions, have pulled off a memorable show called ‘Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century’ that celebrates the museum’s permanent collection (until 12 September). Elsa Smithgall, the senior curator, has edited texts by four dozen contributors for a sumptuous companion volume published in association with D. Giles Ltd. In it Dorothy Kosinski, the museum’s director since 2008 (who will retire next year), writes that Duncan Phillips’ ‘belief in art as a source of solace, a link to wellness, and an essential positive force in society is a key tenet of our program today’. Also to coincide with the centenary, the independent scholar Pamela Carter-Birken has released Duncan and Marjorie Phillips and America’s First Museum of Modern Art (Vernon Press), which reveals how the founders’ aims and personalities are stamped in every room.

The core building, ornamented in terracotta wreaths and ribbons and stained-glass coats of arms, is nestled among unobtrusive additions in the Dupont Circle neighbourhood. Many of the nearby Victorian townhouses and turreted mansions have been adapted into foreign embassies (Morocco and India own properties flanking the Phillips Collection). Duncan’s parents, Eliza Laughlin Phillips and Major Duncan Clinch Phillips, had raised a family there in financially comfortable circumstances. Eliza inherited part of the steel fortune of her Irish-born father James Laughlin, and her husband had been an officer in the Civil War and then head of a window-glass factory in Pittsburgh. Duncan Jr. and his brother James were both slender and long-faced, bearing a youthful resemblance to the actor Benedict Cumberbatch. They were inseparable (their half-siblings Arthur and Florence had died young). ‘James, older by two years, delayed going away to Yale until Duncan was eligible to accompany him,’ writes Carter-Birken.

By 1914, the brothers shared a Manhattan apartment and an annual allowance of $10,000 to buy art. Duncan became a wunderkind critic, connoisseur and patron with varied interests. He wrote books and essays (for periodicals such as Art and Progress) on subjects including Giorgione, Titian, Corot, Marie Bashkirtseff, Gifford Beal (Marjorie’s uncle) and Joaquín Sorolla, and with titles such as ‘The Enchantment of Art’ and ‘The Impressionistic Point of View’. During the First World War he worked for a government agency, the Division of Pictorial Publicity, which promoted depictions of battlefields to build support for the war effort. The museum’s original name, the Phillips Memorial Gallery, was a tribute to Duncan’s father, who had died in 1917, and to James – a victim of the influenza pandemic of 1918 who left a young widow, Alice, and a newborn son, Gifford.

Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880–81), Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

From the opening of the Memorial Gallery in early 1921 – around the same time that Duncan wooed Marjorie with gifts of books and bouquets – artworks of various eras, nationalities, media, and mood were mingled. Carter-Birken’s book reproduces a page from Duncan’s notebook from around 1922, headlined ‘Paintings desired for Phillips Memorial’. It includes works by Manet, Monet, Renoir, Winslow Homer, Albert Pinkham Ryder and Daumier – masterpieces by them all, in Daumier’s case by the dozens, soon entered the collection. At the top of the desiderata list was Renoir’s large tableau of 1880–81, now called Luncheon of the Boating Party. While purchasing it for $125,000 (then a record price), Duncan vowed secrecy to the Parisian dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, lest a press leak provoke ‘protest against allowing so great a masterpiece of French painting to leave France’. Soon after the canvas arrived, the couple’s elder child, Mary Marjorie, suffered devastating brain damage from encephalitis (she died in 1995, after years of institutionalisation). Carter-Birken writes, ‘The Phillips Collection was born in grief and it grew in grief.’

By the 1930s the family had moved a few miles west to a neoclassical mansion called Dunmarlin, a combination of the names of Duncan, Marjorie and their son Laughlin (who would eventually run the museum; among the family members who have remained involved with the organisation is Alice’s granddaughter, Alice Phillips Swistel, who currently serves as a board member). Marjorie kept a ‘Please don’t disturb’ sign on the door of her home studio, where she painted every morning. Her favourite subjects ranged from family portraits to snowy pastures and baseball stadiums. The couple threw parties for luminaries and up-and-comers, who dined amid new museum acquisitions brought home for close study of their effects and interactions. Duncan meanwhile kept up a steady stream of articles and speeches.

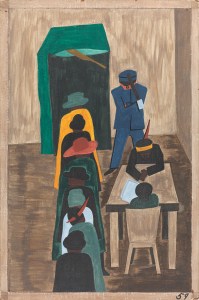

The Migration Series, Panel No. 59: In the North they had the Freedom to Vote (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

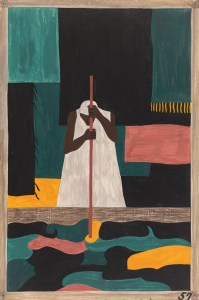

The Migration Series, Panel No. 57: The Female Workers Were the Last to Arrive North (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

In the 1930s Duncan battled anti-foreigner prejudice, arguing that art helps ‘make the whole world kin’. He fostered women’s careers; as early as 1932, he deemed Georgia O’Keeffe ‘an original genius’ and praised ‘her very personal patterns of modulated color planes’. He hung contemporary pieces alongside paintings by El Greco and Goya, to demonstrate ‘the modernity of some of the old masters’, as he wrote in his 1926 volume. In the pace of his purchasing and broad outlook, he rivalled collectors focused on modernist art whose names remain on museum buildings, such as Joseph Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C. and Albert C. Barnes in Philadelphia. In 1942 the Phillips Collection acquired 30 of the 60 panels of Jacob Lawrence’s then brand new The Migration Series (1940–41), one of the first African American immersive artworks to enter the collection of any museum, and it was sent on nationwide tours. Phillips also bought new works by James Lesesne Wells and Horace Pippin, among other African American artists. ‘The Phillips Collection offered a rare beacon of encouragement and support to the African American cultural community during decades when Washington, D.C., was a harshly segregated city,’ Kosinski writes in Seeing Differently.

In 1963, the paint was still fresh on a suite of Mark Rothko abstractions in teals and golds that, for Duncan, induced ‘states of mind weighted with relationships, disturbed or resolved’. Marjorie was always a patient and methodical partner in the decision-making over artworks full of ‘surprise, mystery, indefiniteness’, she wrote in 1985. Yet as the collection and museum footprint grew, the couple maintained the galleries ‘in an unpretentious domestic setting, which is at the same time physically restful and mentally stimulating’, Duncan noted in a lecture in 1961.

It can be said that the couple shaped the worldviews of the artists who visited the Phillips Collection, and those encouraged to curate shows of their own work there. The Washington-based abstract artist Sam Gilliam, an octogenarian still going strong, told Carter-Birken about the importance for the city’s art world of Marjorie ‘being attuned to the life of a painter’. For Richard Diebenkorn, who visited during his military service in the 1940s, the Phillips Collection ‘was a refuge, it was a kind of sanctuary’.

Ocean Park No. 38 (1971), Richard Diebenkorn. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

During my tour, Ocean Park No. 38, from 1971, one of a dozen Diebenkorns in the collection, is on view, aglow in thin layers of Californian lemon tones. The vestibule walls and floor are newly lined with Nigerian-born artist Victor Ekpuk’s State of the Union. Vinyl panels with his black and gold versions of ancient African nsibidi symbols suggest dancers, fists, and cosmic explosions. I am handed a flashlight – how I have missed museum interactives! – in a darkened room, for better views of Hank Willis Thomas’s reflective-vinyl scenes of civil rights protests. A glass bridge between wings brings me to Marjorie Phillips’ 1951 view of a baseball stadium at night: Joe DiMaggio is poised for a pitch below crowds rendered as a blur of colour. In a spiral staircase, I am engulfed in Australian artist Marley Dawson’s new work Ghosts: a series of brass-wire armchairs that dangle and rotate. ‘It’s fun to animate our stairwell,’ Elsa Smithgall explains.

I segue from roomfuls of Lawrence paintings to Wolfgang Laib’s Wax Room: Wohin bist Du gegangen – wohin gehst Du? (Where Have You Gone – Where Are You Going?) of 2013. It is a former closet lit by a bare bulb and lined in 440 pounds of beeswax that echoes the amber hues of the nearby Rothkos. I surreptitiously lower my Covid surgical mask just a little, to inhale the cinnamony fragrance. I imagine the place still inhabited by Phillipses, that I am a party guest who has snuck into a coatroom full of perfumed cloaks.

I am amazed that no mid-century modernist administration ever erased the room configurations of around 1900 and the carved panelling. Fireplaces with stone and wood mantelpieces have tiles in shades of caramel and lichen. Some swathes of Delft tiles, depicting coastal fortresses, have acquired resonances of the slave trade amid contemporary art focused on racism. Zoë Charlton’s The Country A Wilderness Unsubdued (2018), a collage of paper waterfowl and trees emerging from the body of a Black woman, is hung along an oaky switchback staircase carved with foliage and quatrefoil filigree. A tall-case clock is set on huge lions’ paws near the staircase base, alongside Van Gogh’s The Road Menders (1889), with ominous trees dwarfing a village’s workmen and passers-by. While I am dwarfed by a stone fireplace carved with crossed swords, I am briefly alone with Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party. I notice for the first time that the artist carefully dotted a glint in the eye of the terrier held aloft and about to be kissed.

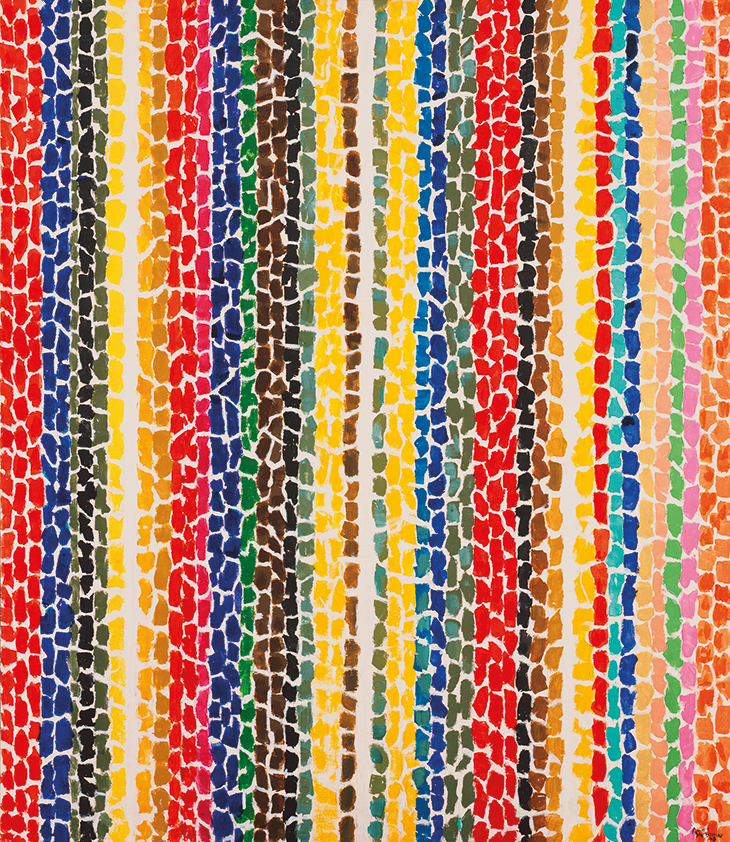

Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers (1968), Alma Thomas. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Kosinski tells me about the eerie parallels between the pandemics that marked the museum’s founding and its centennial. ‘That still blows my mind,’ she says. She describes the institution as ‘changing and dynamic and responsive’, and praises the staff for their ‘power and creativity and nimbleness’ during a nightmarish year. In the ambitious autumn programme are surveys of Alma Thomas – in 1976, Franz Bader, an Austrian refugee turned Washington art dealer, gave the museum her vibrantly striped Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers (1968) – and David C. Driskell, who was encouraged by Thomas to visit the Phillips Collection as an art student in the early 1950s. Smithgall’s interview with Driskell, conducted a few weeks before his death in April 2020, appears in Seeing Differently. He reminisces about the first times he saw the galleries, which showed the work of Black artists in integrated displays: ‘There was a sense of belonging, which was most welcoming.’

For the installations commissioned for this autumn, Nekisha Durrett will cover corridor windows with translucent film images that riff on Lawrence’s Migration Series. Sanford Biggers will layer gallery flooring with coloured sand patchworks, alongside geometric quilts made of leftover cloth scraps by women artisans descended from enslaved populations in the hamlet of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, of which there are several examples in the collection.

During my tour, a Gee’s Bend quilt, Housetop (c. 1960) by Malissia Pettway, is on view. Pettway used flour sacks for backing while stitching concentric polychrome squares in cotton, polyester and damask. The centre panel has pink and white flowers, and the surrounding bands are patterned with tangled nautical ropes. At the foot of this utilitarian bedding, I start thinking of cotton as a fiendishly prickly plant, its bolls sent northwards from Gee’s Bend to be milled; antebellum square garden plots tended by people forbidden to eat the produce; ropes as symbols of captivity, or perhaps hints of longing for escape by riverboat. How many methods of seeing, following the Phillips motto, have come to me.

From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.