Standing in front of Peter Doig’s Painting on an Island (Carrera) in the Courtauld Gallery in London, I am reminded of Edvard Munch’s Melancholy (1891), which hung in the same space just six months ago. Both paintings depict a solitary male figure in profile against a shoreline, in other-worldly surroundings that make the subjects feel all the more remote. In Doig’s painting of 2019 the man is an artist at work on his own canvas, while Munch’s figure appears deep in thought. More tumultuous feelings, however, seem to swell through the painting by Munch, which masterfully captures the anguish of a friend about a turbulent romantic affair. Doig’s portrayal of a painter concentrating on his canvas feels, by contrast, like an entirely imagined, almost mystical scene – albeit one inspired by a real setting, the prison island of Carrera.

Painting on an Island (Carrera) (2019), Peter Doig. Pinault Collection

Though this comparison is never explicitly stated by Doig, he has spoken about his admiration of Munch and his work is filled with references to other artists as well as old photos, films or everyday ephemera including postcards and magazine clippings. For an artist with Doig’s pick-and-mix approach, the Courtauld, with its temporary exhibition space tucked beyond a large gallery of modernist masters, offers much more than a ‘white cube’, inviting the viewer to make their own links between Doig’s work and those from the past. The most obvious example here is the otherwise forgettable Bather (2019–23), its central male figure clearly inspired by Cézanne’s painting of the same name from 1885.

The subjects of Doig’s paintings vary widely, but they often focus on the landscapes that he’s moved through and lived in. In the 11 new paintings now at the Courtauld, we encounter snowy Alpine mountains, the canals of London and the scenery of Trinidad, where Doig moved in 2002 and lived for almost 20 years. While his early works conjured a strange, mysterious wilderness, rendered in frigid tones inspired by his upbringing in Canada, these new paintings feel much punchier. A glaring red bridge cuts through the dense green fauna and murky algae-filled waters in Canal (2023), a portrait of his young son in London. This intensity is used to better effect in Alice at Boscoe’s (2014–23), in which the artist’s daughter melts away amid fluorescent brickwork and blooming foliage, or to amplify the pleasingly moody Self-Portrait (Fernandes Compound) (2015–23).

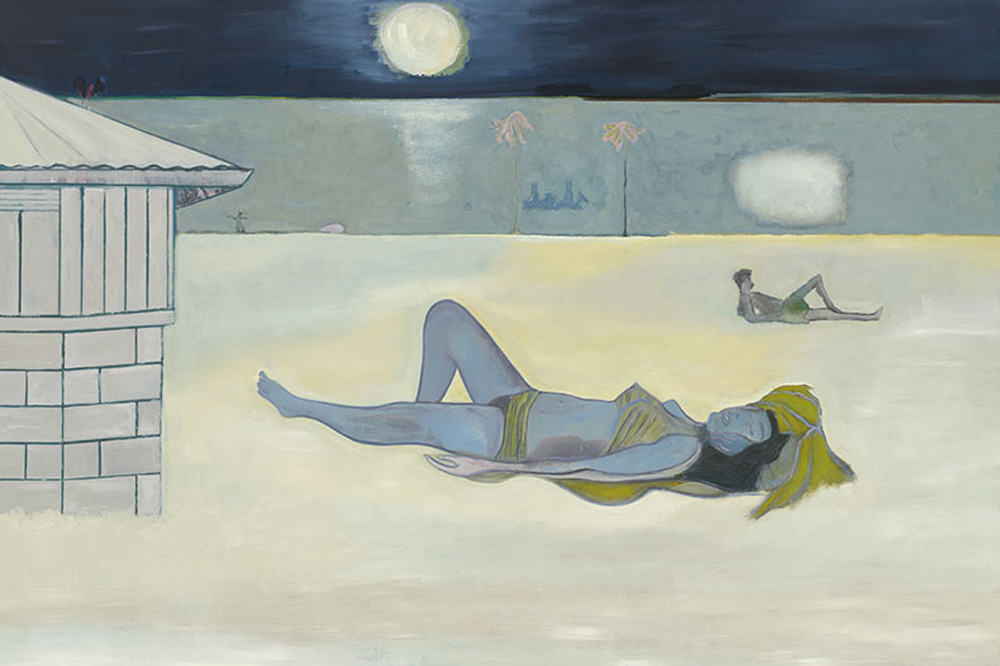

Night Bathers (2011–19), Peter Doig. Private Collection

The use of heightened colour in a work such as Music (2 Trees) of 2019, which depicts a pair of calypso singers serenading a woman on a donkey, makes the painting almost pulsate with imagined sound. This introduces a sensual immediacy to Doig’s hazily-rendered, balmy beachside locale, which might otherwise feel a touch too fantastical. A disquieting remoteness is deployed, however, in Night Bathers (2011–19), an oddly oxymoronic composition in which a woman sunbathes under moonlight on Maracas Bay. The eerie night-time atmosphere is transmitted by a faint purple mist inspired, it seems, by Doig seeing bioluminescent marine animals glowing in the sea.

Doig has always been admired for his handling of paint. The standout work here is the Alpinist (2019–22), an imagined scene based on an old postcard. Off-centre, a skier faces us, standing above a snow-topped forest against a distant mountain. He wears the guise of a harlequin, a nod to Cézanne and Picasso, but the real debt here is surely to the Abstract Expressionists. Viewed close up in the dips and crags of the figure’s snowy perch, Doig’s reworkings and layered application of paint result in a purple-green patchwork of delicate, gauzy planes that have little to do with figuration. Elsewhere, the paint drips, pools and stains the canvas so that what first appeared to be solid ground becomes a shifting, insubstantial surface.

Alpinist (2019–22), Peter Doig. Private Collection

This tension between figuration and abstraction shows how, at its best, Doig’s relationship to the past two centuries of painting pushes far beyond quotation, remixing ideas and approaches to create something that feels singular and compellingly new.

‘Peter Doig’ is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 29 May.