This review of ‘Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance’ at MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, is from the September 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Paula Rego’s first major retrospective in this country for 20 years has a terrific setting in the shiny, new-look MK Gallery – a corrugated stainless steel and glass oasis designed by 6a Architects set amid the roundabouts, office buildings and warehouses of Milton Keynes. The exhibition brings together works by Rego from the 1960s until the present day: paintings, drawings and prints. Rego is a storyteller, often working in series, and the show is full of fairy-tale characters, distorted figures, animals, birds and puppets. Walking through it is a fantastical, unsettling experience; it’s like finding oneself inside the weird and wonderful world of Angela Carter’s novel The Magic Toyshop. Among Rego’s creations, the outside world – and Milton Keynes in its new-town glory – feels very far away.

This is an exhibition of trauma and difficulty and a mild sense of torture is present from the beginning. In Snare (1987), a giant girl looms over a dog that is curled upright on its back while she holds its paws. In Two Girls and a Dog (1987), the girls are trying to dry the struggling animal’s paws with a cloth. In Sleeping (1986), a girl is raising her apron in the background of the painting, perhaps in an attempt to trap the large pelican confronting her with its beak. In The Maids (1987), one maid is manhandling a girl in red on a chair while the other strokes the back of her mistress’s head in a sinister fashion. It’s a painting full of psychic pain; the catalogue note tells us that the stuffed boar is a symbol of the mistress’s ‘absent and impotent husband’. (At the time of the work’s creation, Rego’s husband, Victor Willing, was largely bedridden because of his multiple sclerosis, which had been diagnosed two decades earlier).

The Maids (1987), Paula Rego. Courtesy the artist and Marlborough, New York and London; © Paula Rego

The heart of the show – and in the central room of the gallery – are the works Rego made in response to the failure of a Portuguese referendum that would have legalised abortion, undone by opposition from the Catholic church and pro-life campaigners. Many of these pictures are done in pastel; they are shown at low light to conserve them and the darkness adds to the sense of mystery and gloom. Rego started to work in pastels in 1994 and has described using them as ‘like painting with your fingers’. In an interview, she once said: ‘Brush marks are very evident […] the emotion comes across in brush marks […] I didn’t want to have brush marks, you see.’ Instead she has pastel marks, you see. Her method is to build up layers of pastel, effectively building up a narrative in colour.

In the first part of Triptych (1998), a woman lies curled up on a metal hospital trolley with a bright blue blanket. The blanket is made up of a series of pastel scratches or marks; there are both patches of pale light and pools of dark shadow on its rumpled surface. A black bucket and a black plastic chair sit beside the bed; there are rough pastel hatchings on the chair’s seat. In the third part, a girl in school uniform squats on a black plastic bucket. She wears a striped tie and her dark green school skirt is rucked up around her thighs. She seems to be in a domestic bedroom; the bedcover has flowers on it. But there is nothing pretty about this scene. The girl looks directly out at the painter/viewer, a look of fury on her face.

Untitled No. 4 (1998), Paula Rego. Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art; © Paula Rego

Untitled No. 4 (1989) features another girl in school uniform. This one lies asleep, recovering on a leather sofa that is starting to fall apart, its stuffing coming loose. The girl wears white trainers and white socks – she seems deeply vulnerable. Her head is squashed into the grey pillow, her face distorted. Her hands clutch the sides of the small sofa as she lies in the foetal position in her post-abortion sleep. Rego has said of the way she uses pastels: ‘You draw around the figure and you draw inside the figure. You draw everything in the figure.’ Here, the pastel lines are clearly visible on the girl’s bent legs; there is a pale sheen to her grey school pinafore. Another pastel, Girl with a Foetus (2005), is almost too much to look at. The foetus in the sink is enormous; its umbilical cord wound round the woman’s wrist like some macabre bracelet. She sits on the lavatory next to the basin, her ruffled, floral dress hitched up above her knees. She stares sideways out of the painting – angry and detached at the same time.

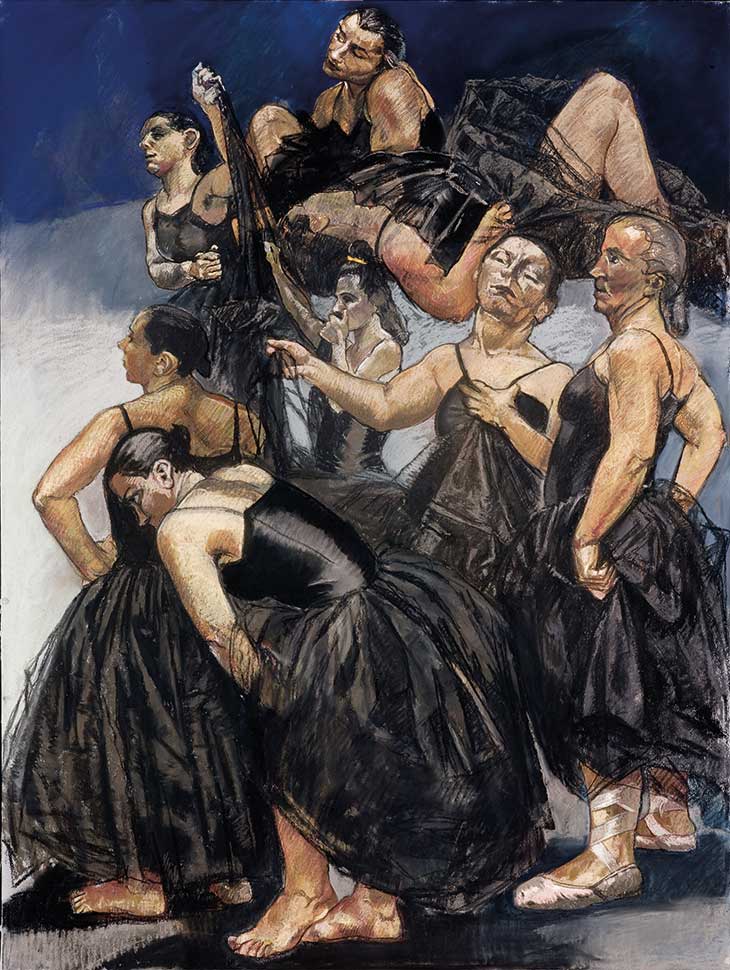

The next room along has a subtle, twisted Disney theme. In Snow White and Her Stepmother (1995) an androgynous-looking Snow White with large thighs steps out of a giant pair of white knickers. There are flawed, fallible human bodies everywhere in this show. On another wall, Dancing Ostriches (1995) – two panels featuring a series of ballet dancers of various shapes and sizes dressed in black tutus – draws on Rego’s memories of the film Fantasia. Including a triptych on each side, this room is like a chapel. Two of the three panels comprising Pillowman (2004) include crosses – one made out of a stepladder with planks of wood taped across it, another a heavy-looking cross being carried on a tiny figure’s back. The works reimagining scenes from The Crime of Father Amaro, a novel by Eça de Quierós, are full of riddles: the battered brown shoes next to the mattress in The Company of Women (1997) seem to echo Van Gogh; a doll lies abandoned under a camp bed in The Cell (1992) in the lap of the central figure in The Coop (1997) is a tiny doll apparently representing her illegitimate baby.

Right-hand panel of Dancing Ostriches (1995), Paula Rego. Courtesy the artist and Marlborough, New York and London; © Paula Rego

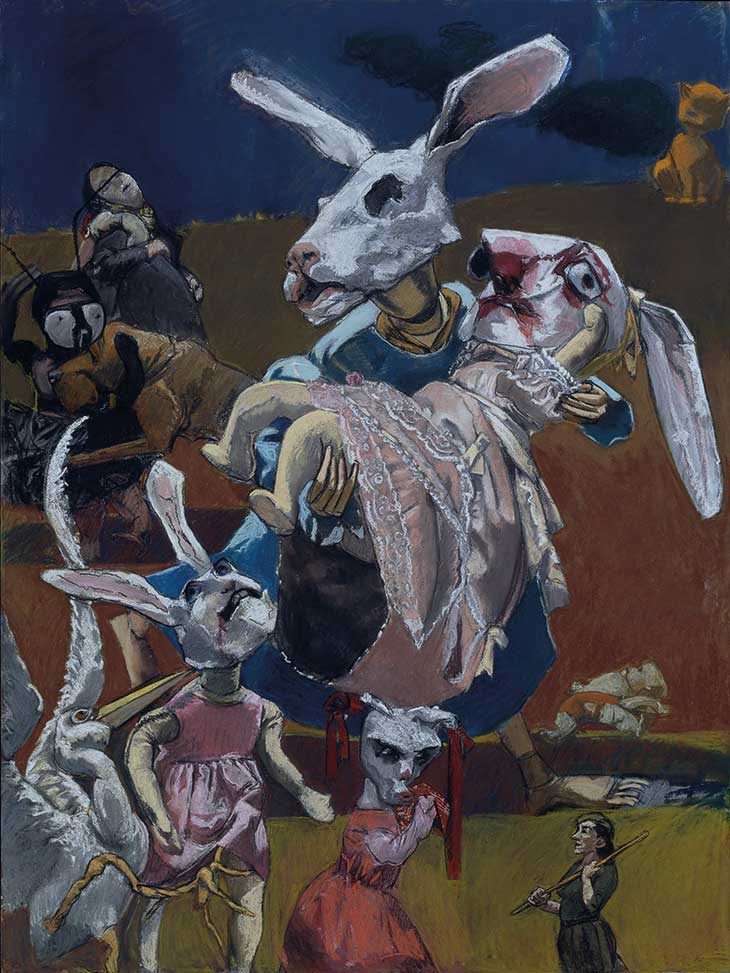

In War (2003), human heads have sinisterly been transformed into the heads of rabbits. In the centre of the painting, one rabbit – in a blue dress – carries another, clearly injured. The work was inspired by a photograph Rego saw in the Guardian at the height of the war in Iraq, of an injured girl in a frilly dress after a bomb went off in Basra. In the corner of the painting, there’s a miniature portrait of Rego’s dance teacher in a soldier’s uniform. As with much of Rego’s work, the colour here is startling – the deep blue of the background before it meets dark sand, which then gives way to a bright yellow. The injured rabbit’s face is marked with bright red pastel, signifying blood.

Rego, who is now 84, has never been afraid to confront strange and difficult things in her work. The title of an oil painting from 1961 says it all. It starts off all bucolic but then comes the kick: When We Had a House in the Country We’d Throw Marvellous Parties and Then We’d Go Out and Shoot Negroes. There is a darkness here and there always has been.

War (2003), Paula Rego. Photo: © Tate, London; © Paula Rego

‘Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance’ is at MK Gallery, Milton Keynes until 22 September.

From the September 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.