The V&A was shaped by powerful personalities, from its founders Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to the first director Henry Cole. Less widely known but also highly influential was Owen Jones (1809–1874), one of the most prolific designers in 19th-century Britain. Jones took a leading role in defining the principles of design reform promoted by the Government Schools of Art and Design, which had their home at the South Kensington Museum, as the V&A was initially known. It is rare that a substantial body of previously unknown work by such a significant historical designer comes to light, but last year just such a discovery was made at the V&A, in the course of answering an enquiry from a member of the public who wanted to know more about a cache of artworks that he owned. As a consequence, the museum was able to purchase a group of 51 original designs for a book of prints that Jones published in 1867.

The connections between Jones and the V&A are many and varied. In addition to establishing the art schools’ design principles, he effectively provided their textbook on stylised ornamental design in the form of his best-known publication, The Grammar of Ornament (1856). As soon as the book appeared, the V&A bought the original designs for the chromolithographic plates prepared by Jones and his collaborators. As part of the deal, the museum also purchased dozens of copies to give to regional art schools in order to disseminate Jones’s design principles around the country. Today the V&A is the major repository of the designer’s work.

Designs for the arcade decoration of the V&A’s Oriental Courts (1863–64), Owen Jones.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the early 1860s Jones was also invited by Henry Cole to design the interior decoration of the museum’s Oriental Courts, as they were then called, where Indian, Japanese and Chinese works were displayed. When he first met Cole, Jones had already carried out extensive interior design in his role as Superintendent of Works for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The decorative scheme for the Oriental Courts was gloriously coloured and richly patterned: effectively a three-dimensional, full-scale version of sections of The Grammar of Ornament. These spaces are currently used as service areas, but initial exploration suggests that much of the original, dazzling paint scheme still survives below later layers of plain paint and, it is hoped, will be restored to sight in future.

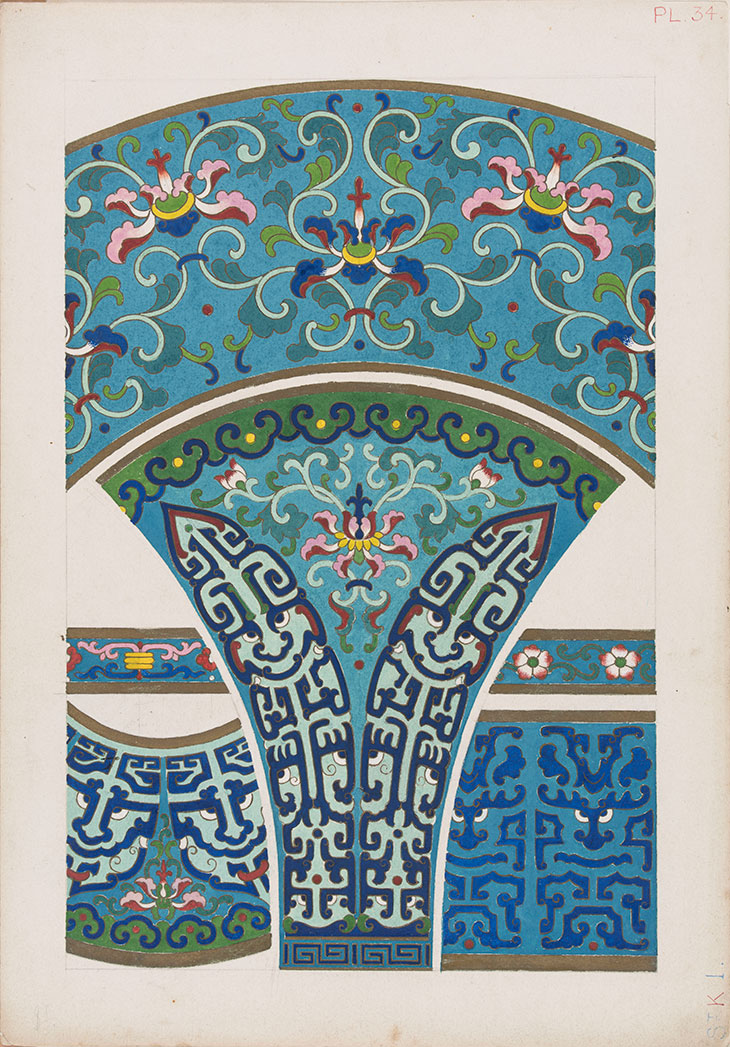

Design based on a cloisonné enamel vase (c. 1866), published as Plate 34 in Examples of Chinese Ornament selected from objects in the South Kensington museum and other collections (1867), Owen Jones. Victoria and Albert Museum

It was perhaps from working on the Oriental Courts that Jones was inspired to publish a book specifically on Chinese, or what he identified as Chinese, ornament. Examples of Chinese Ornament selected from objects in the South Kensington Museum and other collections (1867) presented the public with 100 plates of designs taken from a wide range of decorative and applied arts. Jones transformed motifs found on ceramics, textiles and enamels into densely crafted fields of pattern that could be used as inspiration by contemporary designers. As the title indicates, many of the pattern motifs were sourced from the V&A’s early holdings, as well as from a circle of collectors with links to the museum.

It was a group of almost half the original gouache and pencil designs for the chromolithographic prints published in Examples of Chinese Ornament that surfaced in early 2016. Held in private hands in the United States for many years, they had most recently been taken for printed reproductions rather than the originals. Each design is carefully rendered in pencil and gouache, often with highlights in gold paint, and some bear additional colour notes. In the introduction to the book, Jones describes how he was allowed to borrow items from the V&A’s collection, which he then drew ‘in the quiet of the studio’ in order to abstract two-dimensional patterns from the three-dimensional objects. Unlike the project for The Grammar of Ornament, when he had a team of assistants, for Examples of Chinese Ornament he worked alone. In addition to colour notes in Jones’s hand, which perhaps gave guidance to the printers as well as being an aide-memoire for Jones, each design bears carefully stencilled letters and numbers revealing how plates were carefully grouped together to make the expensive printing process as efficient as possible.

Design based on a cloisonné enamel vase (c. 1866), published as Plate 40 in Examples of Chinese Ornament selected from objects in the South Kensington museum and other collections (1867), Owen Jones. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Indeed, Jones was a pioneer in the new technology of chromolithography. When he produced Plans, elevations, sections, and details of the Alhambra (published in sections from 1836 to 1845), he set up his own presses, as no existing printer could produce what he wanted. He used the same technique for Examples of Chinese Ornament, which allowed him to reproduce the rich colours and gilding found in the original objects. The publication was part of his campaign to repurpose historic material for the contemporary age. Jones intended for these sumptuous plates to function as a design source for new commercial goods – it inspired, among others, Christopher Dresser in his cloisonné-ware designs for Minton.

Design based on a painted ceramic bottle (c. 1866), published as Plate 96 in Examples of Chinese Ornament selected from objects in the South Kensington museum and other collections (1867), Owen Jones. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The last time these designs appeared in any records was in 1876, when they were auctioned at Sotheby’s for 15 shillings. Over the intervening years, their colours have remained remarkably fresh, while their visual and intellectual appeal has only grown. So too has their value – but thanks to the generosity of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund, V&A Members and The Belvedere Trust, it has been possible to bring them home to South Kensington. They are now the focus of detailed research at the V&A, reconnecting the drawings with the original objects in the museum’s collection, analysing Jones’s interpretation of Chinese art and design, and tracing the influence of the publication on the next generation of designers.

Olivia Horsfall Turner is Senior Curator of Designs at the Victoria and Albert Museum