In the opening scene of Ben Lerner’s first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station (2011), the narrator looks on as a fellow visitor to the Prado breaks down in tears in front of Rogier Van der Weyden’s The Descent from the Cross. After a couple of minutes, the man blows his nose, strides into the next gallery, and starts sobbing in front of a small votive image of Christ: ‘Out came the handkerchief,’ writes Lerner, ‘and the man walked calmly into room 56, stood before The Garden of Earthly Delights, considered it calmly, then totally lost his shit.’

It is not hard to imagine how a visitor to the Museo Nacional del Prado, to give it its full name, might succumb to one or other strain of Stendhal syndrome. To walk through its galleries is to encounter room upon room of paintings that have been prized for centuries, first by dynasties of compulsive collectors – the Spanish Habsburgs and their Bourbon successors – and later by artists, art historians and indeed just about anyone who has made the pilgrimage to the Prado. Just think of the thrall in which it held Picasso (who was symbolically appointed as its director in 1936), inducing all those variations on Las Meninas (1656) and The Naked Maja (1795–1800).

The museum’s director, Miguel Falomir Faus, who joined its curatorial department as head of French and Italian painting (up to 1700) in 1997 from a career in academic art history, recalls his own sense of wonder on gaining professional access to the collection: ‘Joining the Prado transformed my way of understanding art,’ he says. ‘When I was first appointed curator of Italian art I was amazed. I remember spending hours and hours looking at the paintings.’ The quality of the collection can perplex visitors, he says, particularly those with little grounding in Spanish history: ‘Americans often ask: “Are these real or copies? We’ve seen these paintings in books, are you sure that these are the real versions?”’

It is a bright January afternoon in Madrid, and we are sitting in Falomir’s office in the Casón del Buen Retiro, a building designed as the ballroom of Philip IV’s pleasure palace, the Buen Retiro, and one that now houses ‘the brain of the museum’ – its library, archive and curatorial offices. There is, in fact, a copy of a painting above Falomir’s chair – a version of Titian’s Venus Blindfolding Cupid, the original of which hangs in the Galleria Borghese, Rome. ‘I’ve devoted most of my life to Titian,’ he says. ‘This was in the storerooms, and I decided I wanted it in my office as a reminder of my former occupation.’

Philip II (1573), Sofonisba Anguissola. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Falomir was appointed director in early 2017, following a period as the museum’s deputy director for conservation and research. Since taking the reins, he tells me, he has focused his energy on two inherited challenges: the celebration of the museum’s bicentenary this year and the planned expansion of the Prado to incorporate the Salón de Reinos (Hall of Realms), once a spectacular royal hall and now, besides the building in which we’re meeting, the only vestige of the Buen Retiro palace to survive. The bicentenary is being marked with an extensive programme of exhibitions and events, some of which reflect on the institution’s history and others of which – such as the pairing of two eminent women artists of the Renaissance, Lavinia Fontana and Sofonisba Anguissola – seem to gesture towards its future. (There are four works by the latter, who was court painter to Philip II, in the collection, but none by the former. The Prado, like other Old Master collections, is only too aware of the lack of paintings by women in its holdings; last year, it rescued Artemisia Gentileschi’s Birth of St John the Baptist [c. 1635] from the storerooms to place it on permanent display.)

The museum may be pulling out the stops for its 200th birthday, but it is only able to do so with such verve thanks to extensive modernisation over the past two decades. When Falomir joined the Prado in 1997, it was under the direct control of the Spanish ministry of culture, an institution that boasted one of the world’s greatest collections of pictures but that seemed lethargic and provincial – as if suffering a long bureaucratic hangover following the Francoist era. ‘It’s hard to recognise the Prado that I joined in the current museum,’ says Falomir. ‘It was a disaster, nothing worked […] It was more like a 19th-century museum than a late 20th-century museum. We did few exhibitions, and most of them were focused on Spanish art: Velázquez, El Greco, Goya, and then the same thing again […] It was a museum with no international context.’

The Surrender of Breda (c. 1635), Diego Velázquez. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

That had started to change in the mid 1990s, as politicians agreed that the Prado lacked the facilities and management structure appropriate to an institution that had long been considered ‘the jewel in the crown of the Spanish cultural system’. Following the approval of an expansion designed by Rafael Moneo, which incorporated the baroque cloisters of the monastery of San Jerónimo el Real into the museum building to provide space for temporary exhibitions and services, the government passed the Museo Nacional del Prado Act in 2003, which granted the museum a far greater degree of strategic and financial autonomy. The previous year, Miguel Zugaza, then a young, managerial director at the Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, had been appointed to lead the institution. Falomir, his former colleague, has nothing but praise for his predecessor: ‘He brought ambition,’ he says. ‘I remember the first time I talked with him and he started to explain his plans. I thought: my goodness, he doesn’t sound like a Spanish director.’

Autonomy has made for a radical diversification of the Prado’s finances, with more than 70 per cent of what is now a €50 million operating budget brought in through museum revenues and fundraising. But the most visible sign of regeneration, besides the Moneo extension, has been an exhibition programme that looks increasingly original and has fully embraced the opportunities of international collaboration. Under Zugaza’s leadership, the exhibitions firmly rooted in home turf began to give way to major monographic shows of Flemish and Italian artists also richly represented in the collection; Falomir himself curated exhibitions on Titian, Tintoretto, late Raphael and others.

Saint Dominic of Silos enthroned as a Bishop (1474–79), Bartolomé Bermejo. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

More recently, the focus has shifted to less-celebrated artists and subjects. When I visit, temporary displays include a beguiling focus on The Fountain of Grace (1440–45), presenting discoveries made during the recent technical study and restoration of the only painting from the circle of Jan van Eyck in the collection, and ‘Bartolomé Bermejo’, an exhibition gathering all attributed paintings by the nomadic medieval master – as if drawn into the force-field of the Prado’s great, glinting altarpiece fragment, Saint Dominic of Silos Enthroned as a Bishop (1474–79). ‘I like to do exhibitions that try to point out a problem in the history of art,’ says Falomir, ‘that try to present a painter who is not well known, like Bartolomé Bermejo, or an aspect of a painter that’s not well known, as we did with Lorenzo Lotto as a portrait painter.’ He continues: ‘I’m not crazy about blockbuster exhibitions: I firmly believe that the blockbuster era is almost over, because exhibitions are more and more expensive and museums are more reluctant than ever about lending their masterpieces.’

Instead, an admirable strategy has emerged of collaborating with other institutions where possible, when it ‘adds to our current knowledge of the field’: a version of ‘Lorenzo Lotto: Portraits’ was shown at the National Gallery in London this winter (its director, Gabriele Finaldi, was Falomir’s predecessor as deputy director of the Prado from 2002–15); ‘Bartolomé Bermejo’ has travelled to the Museu Nacional d’Arte de Catalunya, Barcelona (until 19 May). The closest that the museum will come to a blockbuster this year is with the Spanish leg of an exhibition drawing parallels between Spanish and Dutch Golden Age painting, organised in collaboration with the Rijksmuseum. Falomir is frank when asked to justify the museum’s current touring exhibition in Japan, citing post-crisis funding cuts by the Spanish government: ‘We do these exhibitions because we need the money. If we didn’t need the funds, we wouldn’t do them.’

Ferdinand VII in Court Dress (1814–15), Francisco de Goya. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The revitalisation of the Prado has also encouraged greater reflection on the history of the museum and its collection – an institutional correlative, as it were, to Rafael Moneo’s scheme of folding the remnants of the the royal palace into the ‘Prado Campus’ that will be completed with the planned redevelopment by Norman Foster and Carlo Rubio of the Salón de Reinos. In 2006, the museum published La Enciclopedia del Museo del Prado, which compiles the research of some 130 specialists to provide detailed entries on everything from its architectural fabric to former directors and curators (it is freely available online). The bicentenary celebrations opened in November with the launch of ‘Museo del Prado 1819–2019: A Place of Memory’, an exhibition charting the intertwined fortunes of museum and nation.

The exhibition is a strong statement of how both continuity and radical transitions have made the Prado what it is today. At the heart of this collection, of course, are the artworks collected by generations of Habsburg and Bourbon rulers, from the Flemish masterpieces acquired by Ferdinand and Isabella in the late 15th century, and later by Philip II, to the great, acclamatory paintings commissioned by Philip IV from Velázquez, Rubens and others. When the absolute monarch Ferdinand VII opened the museum in 1819 as the Museo Real de Pinturas, he drew its holdings from the royal collection. Initially, he installed 311 pictures in the building on the Prado (meadow) de San Jerónimo, constructed by Juan de Villanueva several decades earlier to house a cabinet of natural history and academy of sciences for the Count of Floridablanca. (That the museum might have become a Wunderkammer is neatly gestured to in the recent redisplay of the Dauphin’s Treasure, a collection of objets d’art that once belonged to the Grand Dauphin of France, in its north wing.)

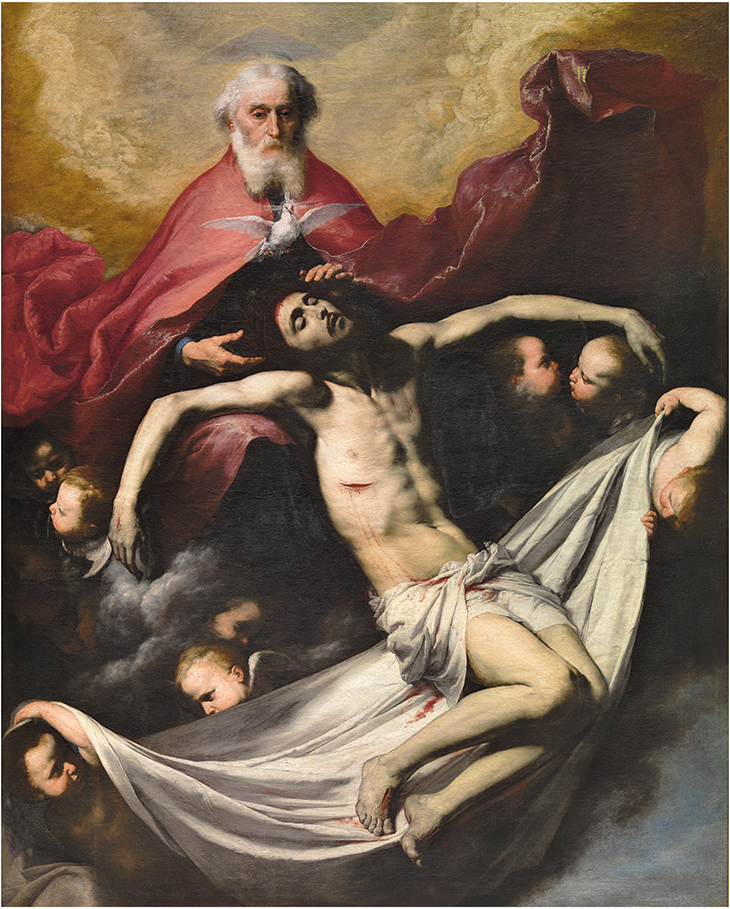

The Trinity (c. 1635), Jusepe de Ribera. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

By 1827, the building housed 4,000 works, most of them relocated from royal palaces; Ferdinand had begun to acquire for the museum in 1820, with the purchase of Ribera’s Trinity (c. 1635) for the collection. ‘It’s amazing how this country has been able to preserve these paintings for centuries,’ Falomir says. ‘It’s a sort of miracle that we have kept them in Spain.’ Their exceptional condition, often remarked on by visitors, is a reflection of the consistency of their provenance: ‘Most of these paintings have been in Madrid for 400 years under the same climatic conditions, with the same owners – first the crown and then the government. It’s amazing how many of the paintings came straight from the painters’ workshops to Madrid. They have not been retouched for other collectors or by restorers.’ Among the most celebrated rooms of the museum is that given over to the battle scenes commissioned from Velázquez, Zurbarán and Maíno for the Salón de Reinos, just a few hundred metres from where they now hang, which include that masterful prospectus for clemency, The Surrender of Breda (c. 1635).

To begin with, the evolution into a more recognisably public gallery was gradual. The first donation to the museum was Velázquez’s Christ on the Cross (c. 1632), given by the Duke of San Fernando to the king in 1828. It was not until after the revolution of 1868, and the deposition of Isabella II, that what had recently been assigned as property of the crown passed over to the state. The Prado absorbed the collections of the Museo de la Trinidad, founded earlier in the century to house Spanish art; much of that had come from disentailed religious establishments such as the College of Doña María de Aragón in Madrid, from where parts of El Greco’s monumental altarpiece were salvaged. The royal museum became national.

The Queen Isabel II gallery in the Museo del Prado (photograph: Jean Laurent, 1879)

Since then, that has meant different things as the political identity of Spain has shifted: ‘Visiting the Prado you understand the history of Spain, and vice versa,’ says Falomir. The current exhibition includes a powerful display of photographs and footage from the period of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–39), when a ‘circulating museum’ of copies of works in the collection staged nearly 200 exhibitions across the country, and from the Civil War, when artworks were shipped for safety to Valencia, then north to Catalonia; in 1939, more than 500 paintings and drawings were dispatched to Geneva. Does the ‘national’ label bring different challenges in 2019, I ask Falomir, at a time when the majority of Catalans have voted in favour of independence? ‘I’ve always understood the word “national” to mean that the museum belongs to all of us,’ he replies, ‘rather than thinking about its political implications.’ As the Spanish painter and writer Ramón Gaya wrote in 1953: ‘When one thinks of the Prado from afar, it never appears as a museum but as a kind of homeland.’

‘I would say that right now this is just about the only institution in Spain that everybody respects,’ Falomir continues. ‘We’ve always wanted to be a national museum. Since the late 19th century, we’ve had about 3,000 works of art on permanent deposit throughout Spain […] The Prado is everywhere.’ There is a historical irony, he points out, in the long-term loan of the museum’s holdings of Spanish polychrome sculpture to the Museo Nacional de Escultura in Valladolid; once considered too humble to keep company with the fine art of painting, such works are now highly sought after by museums and private collectors. In the bicentenary year, the spirit of the circulating museum has been resurrected, with individual works travelling to 30 cities across Spain; the first went to Catalonia, Raphael’s Virgin of the Rose (c. 1517) taking up lodgings at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres – and fulfilling Dalí’s wish, albeit posthumously, to see one of his paintings hanging beside a work by the Renaissance master. ‘We wanted to reinforce the connection between the museum and the country,’ says Falomir.

In Madrid, meanwhile, Falomir is concentrating on diversifying the Prado’s audience, by trying to attract more tourists from East Asia and broadening the demographic of Spanish visitors. ‘I can’t ignore that this a museum of Old Masters,’ he says. ‘Old Masters are not at the peak of their popularity.’ He continues: ‘An Old Masters collection has to be translated for new publics every generation, in the same way that every generation needs a new translation of The Iliad and The Odyssey.’ Here, the strategy has not been to show big-ticket contemporary artists, as some comparable institutions have done – ‘We cannot betray what we are: we are not a museum of contemporary art, but we cannot ignore it’ – but to employ young artists through the education department to help with interpretation. This spring, artists specialising in textiles are running workshops for female prisoners, focusing on Velázquez’s Spinners (1655–60).

Still Life with Vegetables, Game and Fruit (1602), Juan Sánchez Cotán. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The impulse to strengthen the connection between the collection and its public also inspired the museum’s first crowd-funded acquisition, a small portrait of a girl with a pigeon by the 17th-century French painter Simon Vouet. The minimum donation, for a fundraising campaign of €200,000, was set at five euros: ‘It was important to remind people that they could contribute to the expansion of the collection,’ Falomir says. That campaign highlights a larger challenge, he tells me, of a Spanish tax system that provides minimal relief for philanthropic donations. ‘If someone gives you something in Spain it’s because they’re a true philanthropist,’ he says. ‘Our former chairman, Plácido Arango, gave us 25 works from his private collection and didn’t get anything in return.’ The museum has often been able to make acquisitions to fill gaps in the collection, however, thanks to the protective laws that govern cultural property in Spain (‘which collectors and owners are not very happy about – but museums are’). Juan Sánchez Cotán’s Still Life with Vegetables, Game and Fruit (1602), which may be the earliest Spanish still life, entered the collection as late as 1991, for instance; the Spanish kings had preferred their still lifes northern.

Another challenge is the need, even in this bicentenary year, for patience. The museum is eager to start work on the Salón de Reinas this year, and the government has pledged some €30 million to the project, an estimated 75 per cent of the cost. But at the time of going to press, the budget proposed for 2019 has yet to be ratified in parliament, and there is talk of fresh elections if it fails to pass. ‘The political situation in Spain is more complex than ever,’ Falomir admits. Nevertheless, it is a time of optimism at the Prado. Why does the museum need a new building only a decade after the opening of the Moneo extension? ‘It’s just for displaying works of art,’ says Falomir. ‘We’re like an iceberg, in terms of quantity […] and there are at least 300–350 paintings that should be displayed.’ A cure for Stendhal syndrome is not on its way.

From the March 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.