Edvard Munch died in 1944, leaving some 28,000 works to the city of Oslo. Twenty years and many disputes later, the Munch Museum, an undistinguished structure of the Nissen hut school of architecture, opened in Tøyen, a tough and rather out-of the-way neighbourhood in the capital. Norway was not so rich in those days, nor Munch so famous. The museum was cheaply built and inadequately protected. The theft of Madonna and The Scream in 2004 led to draconian security measures, prompting locals to nickname it ‘the airport’. By now, the building also leaked. Action was needed.

With the new millennium, Oslo, now wealthy, was turning its one remaining eyesore, the container port, into a cultural centre. Snøhetta’s marvellous opera house of 2008 was the first building to rise on the edge of the fjord, all white marble angles and planes, like a gigantic ski jump skimming into the sea. Next, a sparkling new national library and small, pretty blocks of flats clustering like barnacles. Shifting light plays on their walls from the little canals running between them. Meanwhile, in 2008, a competition was launched for a new Munch museum, won by the Madrid-based firm Estudio Herreros.

While MUNCH, as the new museum is styled, was rising beside the opera house at the water’s edge, the area became immensely popular. Kite surfers, cafes, pop-up jazz bars and floating saunas started sprinkling the rocks nearby. The opening this October was a joyful celebration, attended by the big guns from the Norwegian royal family and sauna-baked citizens jumping into the water and swimming round the building to cool off. This seemed marvellously appropriate; Munch, like Hockney, loved to paint the illusionistic wobble of bodies breaking the waterline.

Self-portrait with Skeleton Arm (1895), Edvard Munch. Photo: © Munchmuseet

MUNCH has architectural tension. Grey as the rocks it is built on, the building looks like a 60m-high pile of slim books about to topple over at the top, a nice analogy for Munch’s ever self-doubting texts (Munch wrote almost as much as he painted). It was important to him that the painted work was dashed off in the heat of the moment, but that lightning moment of fruition was preceded by a vast body of thought, often written down.

Stein Olav Henrichsen, director of the Munch museum throughout the transition from Nissen hut to $260m national achievement, told me a couple of years ago that what worried him was transporting all those stealable pictures across Oslo. ‘Will you do it all at once with an armed convoy, or bit by bit, covertly?’ I asked. He didn’t say. At the opening he told me, ‘It is important that you don’t need a PhD to enjoy MUNCH.’ That said, one of the opening exhibitions, ‘All Is Life’, doesn’t duck intellectual challenge. It is based on The Tree of Knowledge (c. 1930), the enormous book Munch wrote towards the end of his life, summing up his philosophy. Each wall or segment in the exhibition takes one page of text as a theme, illustrating it with paintings and drawings by Munch, which are arranged not chronologically but associatively. Visitors are encouraged to move texts and postcards around the walls to make their own associations.

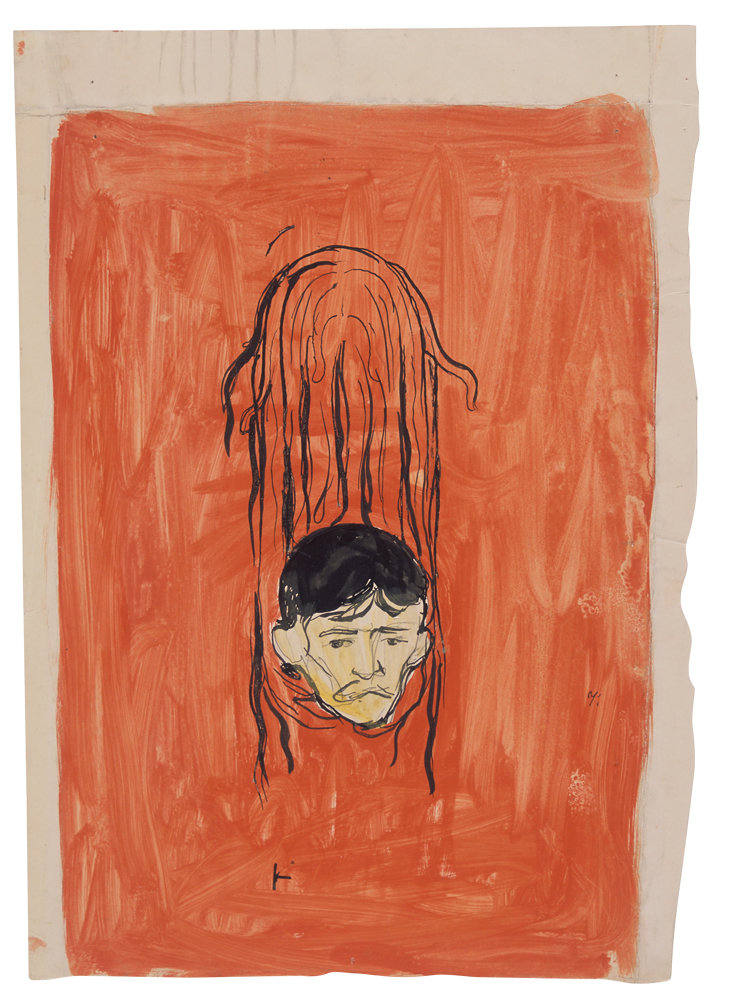

Self-portrait in Woman’s Hair: Salome Paraphrase (1895–96), Edvard Munch. Photo: © Munchmuseet

On the next floor up is the permanent display. Here, ‘Infinite’ contains most of Munch’s best-known canvases, wrenching depictions of life’s cycle through conception, childhood, love, lust, hatred, jealousy, anguish, guilt, existential doubt, sickness and death. Munch chose particular paintings such as Death in the Sickroom, The Sick Child, Ashes, Anxiety, Madonna and The Scream to represent the universal human story. Feeling that the intensity of each individual picture increased when hung with the others, he always wished these pictures to be hung together in a circular gallery, forming an endless narrative ring that he called The Frieze of Life. His wish has seldom been fulfilled.

Madonna (1894), Edvard Munch. Photo: © Munchmuseet

The Scream (1910), Edvard Munch. Photo: © Munchmuseet

MUNCH breaks up the individual components of the Frieze into themes: ‘Death’, ‘Scream’, ‘Naked’, etc. The iconic images are displayed alongside other pictures on the same theme. ‘Death’ works powerfully: big paintings collected from different periods, on blood-red walls. ‘Naked’ and ‘Anxiety’ are more pick ’n’ mix, less coherent, and this dilutes the emotional punch. ‘Scream’ is of course what everyone wants to see. It is housed in a black gallery-within-a-gallery looking rather like a fitted kitchen with three cupboards. The fourth, black, cupboardless wall explains that MUNCH owns multiple Screams: an 1893 version in faintly coloured crayon (probably a preliminary study), the iconic 1910 tempera-and-oil version on cardboard, and six copies of the black-and-white lithograph of 1895 (one hand-coloured). Vulnerable to light, they will be displayed in rotation to limit degradation. Only one cupboard will be open at a time. You have no idea which it will be. This is tough on one-time visitors: if it isn’t the turn of the famous coloured version, disappointment awaits.

Nine more floors of vast galleries present the range of Munch’s art and his mind. His library is far more accessible and better lit than when I wrote my biography some 15 years ago. His photographs, cine films, woodcuts, lithographs and engravings have abundant room for display, as do his monumental paintings of the 1920s and ’30s when Munch, like other artists, dropped private inquietude from his art in favour of making big political statements. As Maurice Denis was hymning anti-capitalist spirituality in Paris and Diego Rivera glorifying industry in Detroit, in Oslo Munch was championing the dignity of labour in his Freia chocolate-factory murals, and scholarship in the Aula university murals.

One of the largest single-artist museums in the world, MUNCH has an enviably flexible 26,313 square metres of adaptable exhibition space, magnificent lighting, totally silent flooring, and terrific scholarship behind the scenes. Its flowerbeds boast Artemisia absinthium, the plant from which that Baudelairean intoxicant absinthe is distilled. Munch, incidentally, was commissioned to illustrate Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du Mal. Skål!

From the December 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.