I’ve been exhibiting with the Weiss Gallery at TEFAF in Maastricht for ten years. Inevitably I come home at the end of it with a cold or flu, but this year I picked up what was clearly Covid-19. As my friend said, you can’t vacuum a virus, especially in a large air-conditioned tent.

I put my sore throat and night sweats down to fair fatigue. But back home in London, I began coughing, a hacking, dry cough like a fox’s bark on a dark night. I was alone with my six-year-old, and had to find a way of getting through it without going to hospital. That first week is a blur for me: gasping for breath, winded by an invisible punch, unable to hold a conversation, crawling on my hands and knees to get from one room to the next, lying flat on the floor, passing out while my daughter tried her hardest to open our heavy Victorian windows and let in fresh air. We never did manage to open them.

Yet in spite of my symptoms – in fact, perhaps because of my intimations of mortality – my imaginative world was heightened. I needed distraction from the way my body was feeling, the way it was failing. And so I disappeared into the past – via the River Thames and the scraps of London’s history that I have picked up on its shores – along with my daughter, my greatest mudlarking companion.

In January, I had acquired a large 1920s haberdashery cabinet with glass-fronted drawers – a display case or ‘Schatzkammer’ for the artefacts I have collected along the Thames over the years. I was lucky enough to grow up near the river and have been picking up London’s historic trash for as long as I can remember. Proper storage for my collection was long overdue. I’d already filled the cabinet and arranged my finds in a semblance of chronological order, but as the weeks went by during my convalescence, and through lockdown, it has provided great distraction. Presenting my favourite discoveries on my Instagram page, @flo_finds, has been my medicine. I’ve sought escape from my body through their fragmented history, in remembering the moment of discovery for each object, imagining myself by the soupy Thames water again.

Below are versions of a series of posts originally published on Instagram in March and April

17 March

Coughing and home, like so many of us, so here’s a bottle that once housed ‘Chas. H. Stevens’ Lung Specific’. I love the emphatic and decorative underlining of the embossed text, and the fact that it came from Wimbledon, in south-west London, a couple of roads away from where I went to school. Charles Henry Stevens was a ‘Lung Specialist’ and this machine-made bottle from a two-part mould dates to around 1915. Stevens was located at 32F Broadway and 204 Worple Road.

Photo: the author

20 March

Here are a few recent little finds. I wouldn’t ordinarily give them much thought, but these are not ordinary times. The garnets were a surprise because they are not from an area where they are commonly found. I have now picked up garnets in varying quantities at FIVE different locations along the river. They are perhaps the Thames’s greatest conundrum, and with this fifth location I am more and more inclined to think they are common industrial waste (from garnet paper-making), rather than in the romantic theory of a ‘jewel spill’.

And to another mystery, that of the ‘M’ crockery. I was thrilled to discover I already had one of these in my little drawer of typographical sherds. These plates must have come from a Victorian London restaurant or hotel, and I wondered about the name of ‘Simm’s’. The Royal Automobile Club was founded on Pall Mall in 1897 by Frederick Simms. However, the apostrophe here is in the wrong place, and the style of writing suggests an earlier date by a decade or two.

Finally, some chubby putti legs, found and given to me by the photographer Hannah Smiles. Probably from a Doulton Lambeth stoneware vase. The fragment is so much more resonant for me than the complete, no doubt monstrous, object. I love them. And I ask you, who doesn’t love a fat baby leg?

(Update: several commenters have convincingly suggested that the pieces of crockery might come from the traditional oyster house, ‘Pimm’s’ – yes, of the drink! – which was first based at Cheapside.)

Photo: the author

22 March

Still home, so mudlarking through my cabinet drawers will have to do. Jetons like this were mass produced through Europe in the medieval and Renaissance periods – their function for counting, rather like an abacus. Think of usurers, merchants and counting houses, or of paintings by Marinus van Reymerswaele. The Low Countries eventually totally monopolised their production, and so this example is a Nuremberg type. Jetons were also used as gambling chips, and were sometimes even purloined by children – so let’s imagine who worked or played with this mid 16th-century one, and which lives hung in the balance.

Photo: the author

27 March

My daughter and I met Denver the Bead Man three years ago, on a bright spring day at the Thames Estuary. A big, burly man, ginger, topless, sweating and burnt in the sunshine, he’d been working hard on an installation of heavy marble fragments from the foreshore which he carefully arranged into an angel, with oyster wings. He’d also been collecting beads, and gave my thrilled daughter his pocketful. Seeing her excitement, he offered on the spot to send her his ‘life’s collection’, if we gave him our address. I was a bit embarrassed and overwhelmed by this spontaneous act of kindness.

I didn’t expect anything further from the encounter, but my daughter clearly hadn’t forgotten his promise. When the postman delivered a compact and heavy package a few months later, she immediately said: ‘it’s from Denver the Bead Man’. She was right.

We’ve been adding to Denver’s bequest with our own bead finds, but his boxful forms the core of our collection. Here is my most special Estuary bead – Czech, turn of the century, and made from clear yellow glass with an intricate applied glass rose.

Why so many beads so far out along the Thames you may ask? Because this was where much of London’s rubbish was dumped in the late 19th century, and also where much of the blitz rubble from Second World War bombings was disposed of. If beads could talk, these little beauties would have a cacophony of stories to tell.

Photo: the author

28 March

And now for some ancient beads – yes, you can call me the bead lady! The one thing I will always find by the Thames is a bead – usually a couple, no matter how ‘bad’ my day, eyes or indeed the tide may be. Beads are hard to date, so the location where they are found plays a huge part in their identification, as do the material, colour, the way they have been formed, and the size of the hole. It’s taken me a long time to get my head around early beads and it’s a bit like looking at Old Master paintings and working out what is a pastiche and what is real. Half the time it boils down to that imprecise and endlessly debatable art of ‘connoisseurship’ and instinct.

Here are some Roman glass examples, as well as stone and bronze (likely Anglo-Saxon or medieval).

Photo: the author

28 March

And more of my antique beads from the Thames. Here we are looking at a predominant date range between the 16th–18th centuries, starting with the decorative ‘trade’ or ‘slave’ beads, used by European merchants in their trade with African tribes and Native American peoples.

Photo: the author

Then we have other natural materials – terracotta (these examples have lost their Tudor-green glaze except at the core); incised bone; and red and white coral. Coral was often used in children’s jewellery as it was believed to ward off evil spirits and protect against infant mortality.

Photo: the author

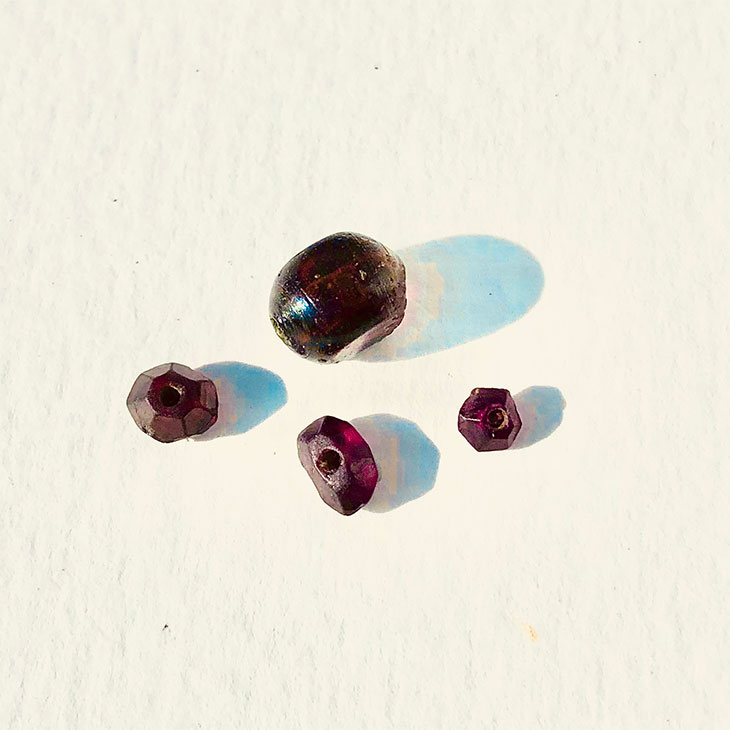

Finally, some hand-faceted spinel beads. When I first found these I wrongly assumed they were garnets, which they are not. I also wrongly assumed they were therefore Victorian or Edwardian. But spinels were most popular in the Tudor and Jacobean periods, as substitutes for rubies. These particular beads are delightfully wonky, and have resonance with the famous ‘Cheapside hoard’.

Photo: the author

29 March

With many of us in lockdown, I thought I would tell the story of the willow pattern birds, and their flight for freedom.

Once there was a wealthy Mandarin who had a beautiful daughter, more beautiful than a flower. She fell in love with her father’s humble assistant notary, but was already promised to a nobleman. Her father built a high fence around his house to keep the lovers apart, and arranged her wedding to take place on the day the blossom fell from the willow trees. Her grand fiancé arrived by boat in good time to claim his bride, bearing a box of jewels as a gift. But on the eve of the wedding, the heartbroken notary disguised himself as a servant, slipping into the palace unnoticed. As the lovers escaped with the box of jewels, an alarm was raised. Running over a bridge, they were chased by the bride’s enraged father, whip in hand, and a little army of men in boats. The gods, moved by the couple’s plight, transformed them into a pair of doves. The doves, as you will see from my sherds, are locked in a perpetual kiss.

The story behind this chinoiserie is so whimsical. Ordinarily when I encounter willow-pattern fragments on the Thames foreshore they frustrate me, but stuck at home, I can appreciate the narrative in these little pieces of broken blue and white. In the 18th and 19th centuries most of London seems to have dined off willow-pattern plates, and really, now I think, how lovely!

Photo: the author

April

I’ll aim to upload a different drawer from my Schatzkammer every day (that’s treasury to you and me). In other words, my ‘river tat’, as so-called by my better half. Starting with delftware. Thank you Larry [of Lawrence Steigrad Fine Arts] for the suggestion!

Today

Am I better? No. But I’m getting there. I’m on antibiotics for pleurisy, and having never been asthmatic before, I’m now using inhalers to ease my breathing. When I can go for a walk around the block without feeling pain in my chest, when I can run up and down the stairs, chase my daughter and ride my bike again, when I can wake up and literally smell the coffee, when I can finally make it back to the Thames – then I will be better. In the meantime, I shall escape to the past with my cabinet of mudlarking mementoes.

Mudlarking the River Thames requires a permit from the Port of London Authority, which can be applied for online. All activities along the river, including mudlarking, are prohibited during lockdown.