On 14 November last year, a who’s who of sculpture historians gathered at the Church of the Holy Ghost and St Stephen in West London. The occasion was the funeral mass for Benedict (Ben) Read, sculpture scholar extraordinaire, author of the monumental Victorian Sculpture (1982), and youngest son of modern art guru Sir Herbert Read. My first meeting with Ben was at the preview of the exhibition ‘Hamo Thornycroft: The Sculptor at Work’, at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, in 1983. Blissfully unaware of his identity, but discussing the changed environment with regard to the appreciation of Victorian sculpture, I blithely remarked that one of the things that had altered was that ‘the dead hand of Herbert Read [was] no longer around’. After a moment’s pause and a look of shock and horror, there followed a burst of laughter and the response: ‘Yes, when I was at the Courtauld Alan Bowness always told me that I had to correct the balance.’ Over 30 years of friendship and occasional collaborations ensued, especially the exhibition ‘Sculpture in Britain Between the Wars’ at the Fine Art Society in 1986.

Like Ben, I seem to have spent much of my life reappraising the work of neglected figures – in my case from the 1920s and ’30s – and trying to correct the balance through exhibitions and articles, reappraising the work of overlooked artists such as Adrian Allinson, Gilbert Bayes, and Ethelbert White. A crop of exhibitions this year promises at last to consign to the dustbin of history that long outdated prejudice that lauded abstraction while condemning figurative art to eternal oblivion. The division was as much political as aesthetic, sundering not only the generations but causing dissension between friends. Influenced by Pevsner’s Pioneers of Modern Design (1936), the interwar and immediate post-war years became a period of blinkered intolerance on both sides, which reached its nadir with Alfred Munnings’ speech attacking modern art and Picasso at the Royal Academy dinner in 1949. Looking back now from the second decade of the 21st century it is quite clear that quality was never the prerogative of either the modernists or the traditionalists. There was always good and bad abstract art, just as there was good and bad figurative art.

‘The Mythic Method’ (at Pallant House, Chichester, until 19 February) explores the theme of classicism in British art between 1920 and 1950, juxtaposing, for instance, Meredith Frampton’s austere 1928 portrait, Marguerite Kelsey, with Ben Nicholson’s 1933 (St Rémy, Provence), with its obvious references to Picasso’s neoclassical works of the previous decade. It also makes a strong case for re-evaluating the reputations of such long-neglected figurative artists as John Kavanagh, Lancelot Glasson, and Ernest Procter. ‘Sussex Modernism: Retreat and Rebellion’ (at Two Temple Place from 28 January–23 April) takes up the theme, but with a wider remit with regard to subject matter, embracing works as diverse as John Piper’s Brighton Aquatints, Vanessa Bell’s late self-portrait and Salvador Dalí’s Mae West Lips Sofa, all drawn from collections on the south coast. Later in the year the major summer show, ‘True to Life: British Realist Painting in the 1920s and 1930s’, at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (1 July–29 October) will demonstrate even more clearly that there has always been more than one way to be ‘modern’. This ambitious exhibition, with its concentration on the hard-edged (rather than broad-brush) approach to realism, will include works such as John Luke’s cold-blooded modern-dress Judith and Holofernes and Harold Williamson’s Spray (which featured on the cover of the May 2006 issue of Apollo).

The Day’s End (1927), Ernest Procter Leicester Arts and Museums Service

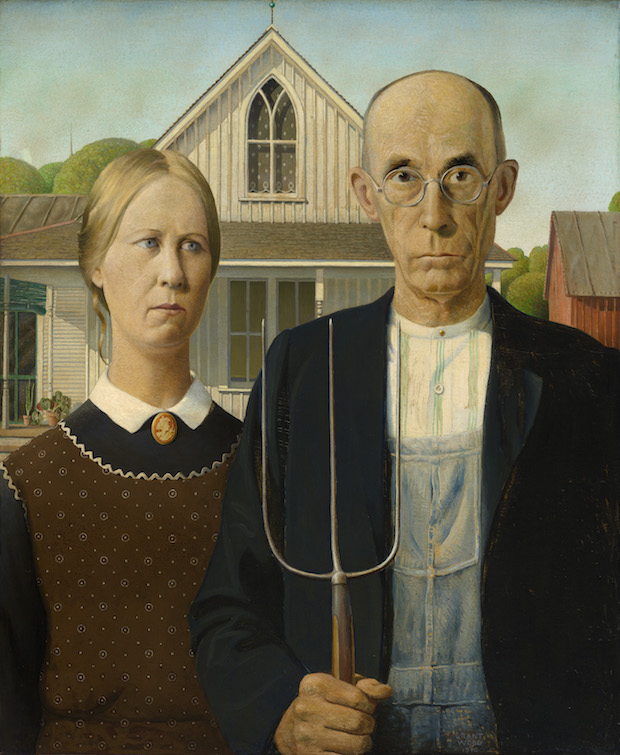

The Royal Academy’s ‘America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s’ (25 February–4 June) will also concentrate on works by figurative artists of the period – among them Charles Sheeler, Thomas Hart Benton, and Edward Hopper – and include that great icon, American Gothic by Grant Wood. Wood’s uncompromising depiction of an austere Midwest farmer and his wife (posed for by his sister and his dentist) in front of their gothic wooden homestead, evokes the harshness of life in the American heartland during the Depression years, in the way that no non-figurative work could ever do. It justly deserves its status, and is among that small band of works that have penetrated so deeply into the public consciousness that they can be appropriated by cartoonists and others without further reference.

American Gothic (1930), Grant Wood. Art Institute of Chicago

London’s National Portrait Gallery has just acquired, after several years on loan, Joseph Southall’s The Agate, a painting that in its directness and the strange inscrutability of its subjects, is the closest parallel that modern British painting has to American Gothic. Although Southall was 30 years older than Wood, there are many correspondences between their work, derived in part from their shared Quaker heritage which, among other things, led each of them to prefer to stand aside from the cultural centres of their respective countries – Wood in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and Southall in Birmingham. This enabled them to protect their integrity of vision without in any way rendering them provincial: both travelled extensively in Europe and were fully aware of current trends. Southall had a major exhibition at the Galeries Georges Petit in Paris in 1910 and exhibited regularly at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, while Wood studied at the Académie Julian and in 1926 held a substantial exhibition at the Galerie Carmine.

The Agate (1911), Joseph Edward Southall. National Portrait Gallery, London

More important was their shared love and emulation of Renaissance portraiture, with its ruthless honesty and uncompromising directness of vision. In Southall’s case, this discipline was enhanced by his use of tempera, a demanding medium requiring great accuracy in the execution. This often gave his figures an air of frozen monumentality, as in The Agate. This somewhat disconcerting double portrait shows himself and his wife, Bessie, elegantly attired, collecting agates on the beach at Southwold, which she used for burnishing the gilded frames of her husband’s paintings.

From the January 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.