Quite what Martin Boyce means to do by titling his current exhibition at the Fruitmarket in Edinburgh after one of the lewdest single lines of Elizabethan poetry isn’t immediately apparent. Shorn of the line that precedes it – ‘Licence my roving hands, and let them go’ – ‘Before Behind Between Above Below’ could mean almost anything. John Donne’s words become abstracted into ‘prepositions that place us in relation to our environment’, as the exhibition’s introductory wall text unsexily has it.

Boyce – who won the Turner Prize in 2011, but remarkably hasn’t had an institutional show in Scotland, where he was born and lives, since 2002 – once explained in an interview that he came to Donne’s couplet at a remove, via Philip Roth’s novel Professor of Desire. This seems fitting, given that Boyce brings you to pretty much every subject at one or more removes, so much so that the overwhelming sensation his work instils in you is that of being placed at a remove from your own experience.

The Fruitmarket’s lower gallery, where the exhibition starts, includes For 129 Fear View Lane (2000): a plywood filing cabinet, painted in primary colours such that it looks a bit like an outsized Rubix cube; more recent installations such as No Information or Memory (2021), which comprises a chair tilted so as to fasten shut the handle of a door; and an array of photographs, prints and other wall-based works that hint at hidden depths to which the works contrive to deny all access. In Phantom Limb (Sister) (2002), the famous plywood-moulded leg splint designed at the behest of the US military by Charles and Ray Eames during the Second World War is blurred out and monochrome, its ghostly contours dissolving into a black background. The purpose of the splint, like the warm brown tones of the plywood from which it was shaped, is a hazy memory; the photograph looks like an out-of-focus shot of a Henry Moore.

Installation view of ‘Martin Boyce: Before Behind Between Above Below’ at the Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. Photo: Stefan Altenburger; © Martin Boyce

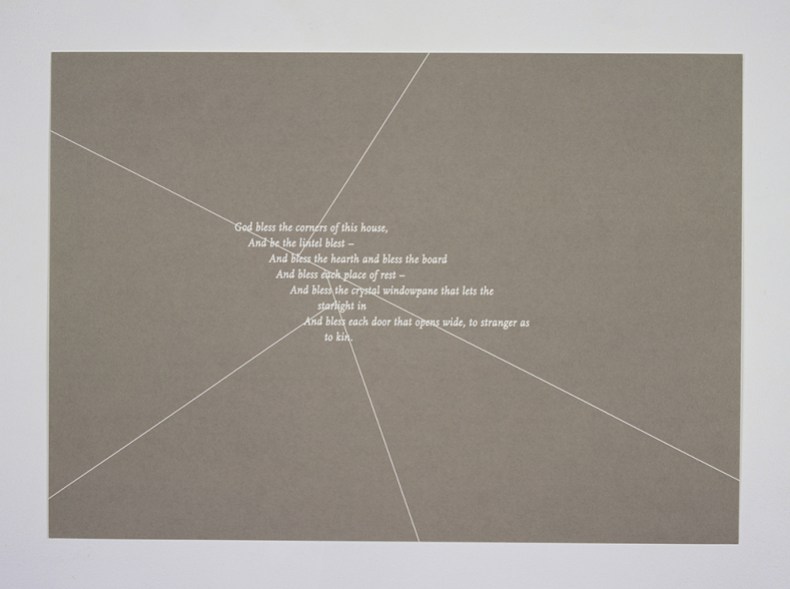

Something similar happens in House Blessing (from the White Album by Joan Didion, 1979) (1999). Here, a kitschy verse beginning ‘God bless the corners of this house’ appears in a silkscreen print: tiny white text enveloped by its cold grey background, overlaid and disrupted with a minimalist spider’s web of straight white lines. In The White Album, Didion tells us that this verse was framed in the home of her mother-in-law and always induced in her a ‘physical chill, so insistently did it seem the kind of “ironic” detail the reporters would seize upon, the morning the bodies were found’. ‘And bless the hearth and bless the board’– there can be little more dispiriting, physically or conceptually, than a cold hearth, and by divorcing these lines from their context, Boyce succeeds in ramping up the chill factor.

House Blessing (from the White Album by Joan Didion 1979) (1999), Martin Boyce. Courtesy the artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow/Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, Vienna/Esther Schipper, Berlin, Paris, Seoul/Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, Los Angeles; © Martin Boyce

Elsewhere, trees are turned to concrete – a nod to the work of Joël and Jan Martel, who in 1925 constructed four 15-foot-high cubist ‘trees’ for the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. But where the Martel’s little concrete grove was rooted in actual soil, in Robert Mallet-Stevens’ Garden of Modern Housing, the shapes Boyce has cribbed from it are here suspended from the ceiling, or else represented in another X-ray-like photograph. Again and again, Boyce gives us abstractions of abstractions.

Why? His work removes us, but does it move us? The answers to both questions lie above, and below. In the Fruitmarket’s gloomy Warehouse space are a series of photographs of the burnt-out husk of Rennie Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art; another plywood cabinet, this time painted uniform black such that, where the first cabinet invited curiosity as to what might be contained within, this one provokes only foreboding; and further dispassionate sculptures in steel, wood and concrete. In one sense, then, this seems to be work about the experience of lack – whether that is physical or psychological emptiness, amounting in the case of Spook School (2015) to a kind of grief. But that’s not the whole story. On ascending to the Fruitmarket’s Upper Gallery, visitors are met with a glittering canopy: this is Future Blossom (for Yokeno Residence) (2022), with geometric, perforated forms of aluminium and steel painted white and pink and suspended beneath the Fruitmarket’s skylights. Across the floor are sparingly scattered petals of paraffin-coated crepe paper – and on the far wall is a clever bit of trompe l’oeil, a recessed fireplace of jesmonite and ciment fondu entitled Same Day (2015). It is painted black, with a little open doorway transforming it from another cold hearth into a kind of Beckettian stage.

Same Day (2015), Martin Boyce. Courtesy the artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow/Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, Vienna/Esther Schipper, Berlin, Paris, Seoul/Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, Los Angeles; © Martin Boyce

Here, at last, Boyce begins to show his hand. This is work that casts you back on your own devices, your own imagination, so that absence becomes productive. It’s descended from John Cage’s silence, or Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing – art that gives you not quite enough to fill in the gaps, but enough to spur you to give it a go. Set at ankle height around this room are five ventilation grills, on which are written the five prepositions of the exhibition title. Seen in the abstract, the fact that they’re all positioned at the same height renders them apparently meaningless. But the actual experience of the work is such that as you cast your eyes around and attempt to resolve the disorientation between your bodily senses and your mind, your awareness of the relationship between these two becomes heightened. It’s not quite a licence for roving hands – the Fruitmarket’s insurance probably wouldn’t cover that – but it is a licence to revel in the roving of the mind, and the ways it helps us anchor ourselves in the world.

Installation view of Ventilation Grills (for an Apartment Building) (2003) and Somewhere there are Trees (2022) by Martin Boyce at the Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. Photo: Stefan Altenburger; © Martin Boyce

‘Martin Boyce: Before Behind Between Above Below’ is at the Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, until 9 June.