Seventy-four years after she mounted the scaffold in the Place de la Concorde, Marie Antoinette returned to the Petit Trianon. Once again, her likenesses, rendered by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller, gazed down from the neoclassical boiseries of her private retreat. White marble busts of the executed king and the dauphin turned unseeing eyes on reinstated Sèvres vases, gilded cabinets and an ostrich egg painted with a fête galante by Jean-Étienne Lebel. This imaginative recreation of the Trianon as Marie Antoinette might have known it was the world’s first exhibition devoted to France’s most famous queen, curated by the country’s third empress, Eugénie, who also contributed many relics she had collected herself: a book of samples from Marie Antoinette’s wardrobe, a signet ring, a fruit knife. The 1867 exhibition helped spark a popular fascination with its subject that has hardly dimmed in the intervening years. The latest, ‘Marie Antoinette Style’ at the V&A, sets out her ‘influence […] on over 250 years of design, fashion, film and art’, and traces a cultural legacy that is almost always described as ‘complex’.

Marie Antoinette’s reputation during her lifetime was well-trodden ground – particularly the tendency of the people to make her a focus for their hopes, fears and hatreds. However, by the early 19th century, the Ancien Régime had become sufficiently distant to be a subject for reverie and its nostalgic appeal was encapsulated by Marie Antoinette, whose execution in 1793 famously prompted Edmund Burke to declare that ‘the age of chivalry is gone’. In Second Empire France, association with the ‘age of chivalry’ gradually became a source of national identity and personal pedigree. A mid 19th-century pink dress with an apron made of 18th-century embroidered taffeta embodies what one contemporary journal considered the fashion sensation of 1837. The appeal of the romantic ensemble lies in the suggestion that its wearer – presumably a daughter of the new generation of urban doctors and lawyers – might have turned up a stash of family heirlooms from the attic. This idea had a particular importance for the Empress Eugénie. Born Eugénie de Montijo, she – like Marie Antoinette – was a foreign-born royal consort whose political power would ultimately prove contingent; her husband was overthrown in 1870.

The V&A bows to no empress in spectacle. At the entrance to ‘Marie Antoinette Style’, a projection of Joseph-Siffred Duplessis’s 1772–73 portrait of the 15-year-old Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria, as she then was, bursts creepily into an animated smile. Elsewhere, ornate panier-flanked dresses glitter in a chandelier-lit hall of mirrors and visitors can place their noses to porcelain replicas of Felix Lecomte’s bust of the queen rom 1783, to sample scents with which Marie Antoinette might have been familiar, from the beeswax candles of Versailles and the cut grass around the Trianon to the stench of rot, sweat and human misery permeating the Temple Prison. Midway through the exhibition, a darkened room displays the queen’s sweat-stained chemise and the guillotine blade ‘reputed to be the blade that beheaded Marie Antoinette’, apparently obtained from the executioner by the sons of Madame Tussaud.

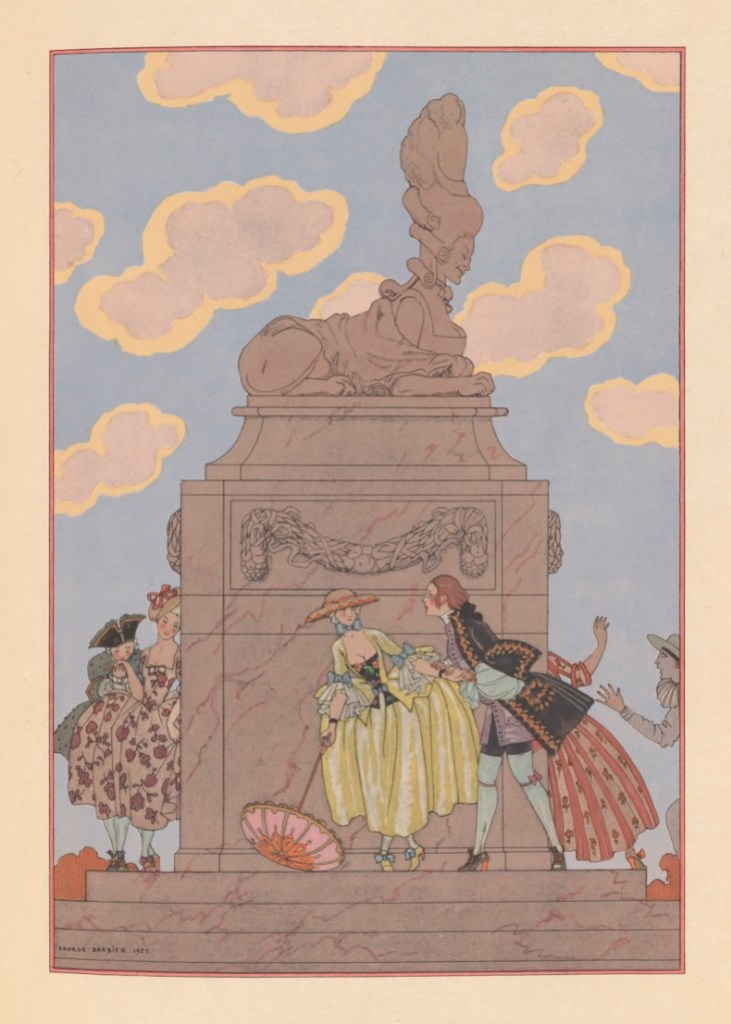

Despite this bodily invocation of the dead queen, only a few object labels are granted the authenticating ‘MA’ monogram, marking objects with an undoubted royal provenance. However, after a while it is difficult to remember (and several of the other visitors had clearly forgotten) that those illusionistic diamond brooches in the shape of a bow are of the place and period, rather than specifically of the queen, or that a white cotton shift dress is merely of a type with which Marie Antoinette would have been familiar. It makes no difference to the richness of the material on display, but the slippage between history and ‘style’ emphasises the vacuity that seems always to have hung around Marie Antoinette. This may partly be the paucity of really convincing or evocative contemporary likenesses from among the volume of material produced about and around the queen (Vigée Le Brun’s much copied efforts notwithstanding). But it probably also speaks to the power of the story. In her 1967 essay on Howard Hughes, Joan Didion suggests that ‘our favourite people and our favourite stories become so […] because they illustrate something deep in the grain’. Marie Antoinette’s trajectory from opulence and adoration to desecration and destruction slips a little too seamlessly into mythology – the end of chivalry, the fall of empires. Perhaps this is why she reappears in art deco form (imagined by Paul Verlaine and George Barbier) in the reckoning that followed the First World War. A series of satirical prints from the end of her reign show Marie Antoinette variously as a whore, a hyena and a chimera, and it is the last – at least in its figurative sense of a mirage, an illusion – that seems most apposite. Marie Antoinette has always been what we make her.

‘Marie Antoinette Style’ is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, until 22 March 2026.