From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In the early years of the 20th century, a number of pioneering women artists in Germany began to take an active role in exploring avant-garde ideas, often with startling results. If recognition of their signal contribution to the forging of the language of Expressionism was slow in coming because of gender bias, that historical injustice is now being vigorously redressed by a new generation of scholars and curators. A case in point is the exhibition ‘Making Modernism’ at the Royal Academy (12 November–12 February 2023), which will be the first in the UK to focus on Käthe Kollwitz, Paula Modersohn- Becker, Gabriele Münter and Marianne Werefkin together. What marks Werefkin out among these four female trail-blazers is the fact that she was actually born and raised in Tsarist Russia. A complex personality whose reputation rests on the paintings produced during an intense seven-year period in Munich before the First World War, she never forsook her native identity and was given Orthodox funeral rites when she died in the Italian-speaking Swiss town of Ascona in 1938. As both an émigré and a modernist artist, Werefkin remained a taboo figure in her homeland until the late 1980s, but her Russian identity has been reclaimed in recent years thanks to the opening up of far-flung archives, and an enduring fascination with the ‘amazons’ of the pre-Revolutionary avant-garde, of whom she was one of the very first.

The artist who became known as Marianne Werefkin was already in her mid thirties when she moved to Munich in 1896. Until that point she had lived as Mariamna Verevkina (pronounced ‘VerYOVkina’, with the stress on the second syllable). Born in Tula in 1860, she was the exact contemporary of Chekhov and his friend the landscape painter Levitan, but unlike them enjoyed a privileged upbringing in a cultivated noble family who encouraged her artistic leanings. It was not a typical Russian childhood. Her father Vladimir Verevkin was a high-ranking general in the army, whose successive postings in Vitebsk (now in Belarus), Vilna (current-day Vilnius in Lithuania) and Lublin (now in Poland) meant his daughter was exposed early on to the multi-ethnic colonial realities from which most Russians of her class were shielded. The three cities on the far western edge of the Russian empire were all in the Pale of Settlement, and home to oppressed Jews, Lithuanians and Poles. As a consequence, when Werefkin finally got to know the ‘real’ Russia, during a visit to relatives in Tambov province at the age of 18, it seemed foreign. Home to her became Vyzuoneles, a lush country estate near the Lithuanian city of Kovno (current-day Kaunas), which was given to General Verevkin in 1879 after he helped its owner escape a death sentence for his supposed involvement in the Polish independence movement. The Verevkins gave the estate the Russian name of Blagodat (‘divine blessing’), installed Russian furnishings and servants and erected a wooden building in the grounds for their daughter to use as a studio during the summer, when they were resident.

Werefkin began painting in her teens, and was immediately encouraged when she showed precocious talent as a portraitist. This led to her developing a close personal association with Russia’s greatest exponent of the genre, Ilya Repin, during family visits to Moscow, long before her father was posted there in 1883. She continued to focus on portraiture while studying for two years with Illarion Pryanishnikov at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. In 1886 she embarked on ten years as a private student of Repin after following her newly widowed father to St Petersburg, where he had been appointed commandant of the Peter and Paul For- tress, in the heart of the city. Dostoevsky had been one of the many political prisoners in its notorious jail, known as the ‘Russian Bastille’, but Werefkin was undeterred by the associations, and converted an airy room in the Commandant’s House into a studio.

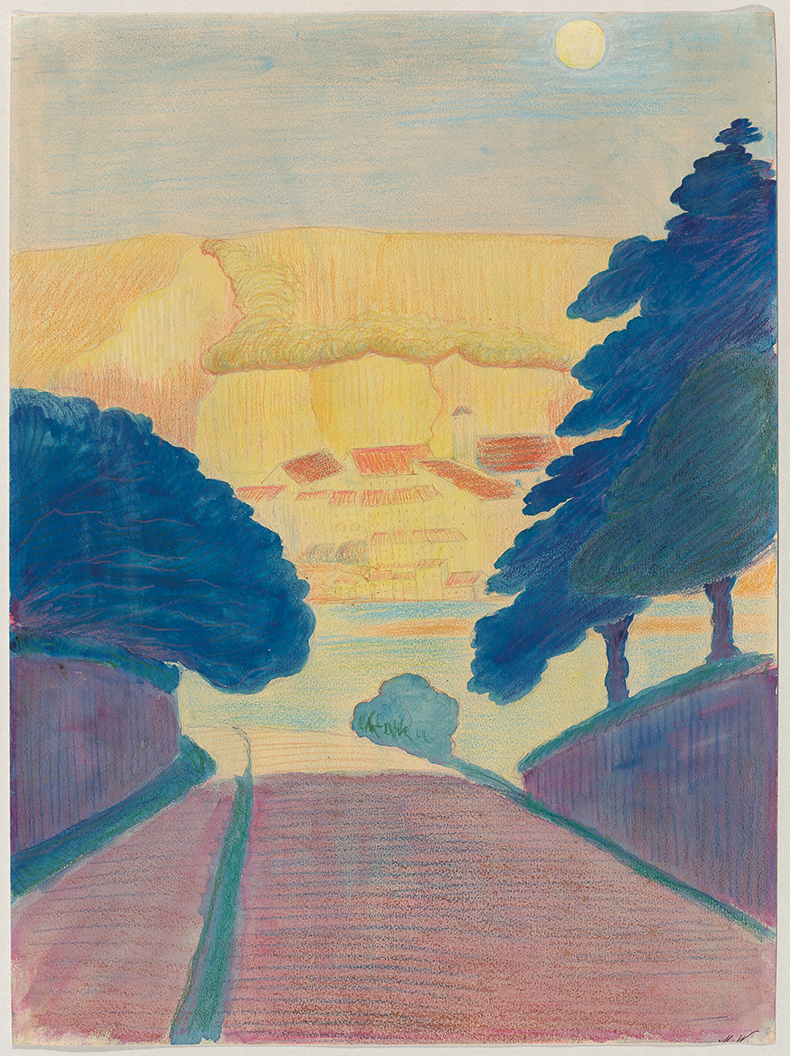

Wasserburg (1907), Marianne Werefkin. Lenbachhaus, Munich

By the time Werefkin reached her twenties, she had developed into an unusually single-minded and intellectually curious young woman, fearless in her flouting of societal expectations. In one letter sent to her father from Blagodat she expressed contempt for pursuing ‘so-called feminine pastimes’ such as putting on a gown, going to balls and enduring the ‘obscenity’ of being appraised like a horse put up for sale. Instead, she openly preferred dancing outdoors with local villagers, sleeping in barns and hunting, and was stoic in the face of adversity. Soon after she accidentally leaned on a loaded gun and shot herself in the right hand, Repin painted Werefkin’s portrait, pointedly showing her smiling beatifically, all in white, with her arm in a sling, leaning against the back of a white wicker chair. After a year of painful treatments, which left her hand permanently disfigured, Werefkin doggedly returned to painting, and began the first of the 65 notebooks she would complete over the course of her life in which she made notes on whatever she was reading.

Opportunities for artists to exhibit professionally in Russia during the reactionary regime of Alexander III were few and far between. Nevertheless, in 1892 Werefkin succeeded in becoming one of the first female artists to have a painting accepted by the popular Association of Travelling Exhibitions. It was in this fateful year that Repin introduced her to another of his protégés, Alexei Yavlensky. Due to straitened circumstances, the artist who would become known as ‘Alexej Jawlensky’ in Germany, had been compelled to follow his late father into the military, and he was only able to become a part-time student at the Academy after he was transferred to St Petersburg in 1889. He was 28 when he met the vivacious 32-year-old Mariamna Vladimirovna in 1892, and they instantly forged an intense but complicated romantic bond, united by their increasing dissatisfaction with the insularity and conservatism of Russian art. The situation hardly changed when long overdue reforms at the Imperial Academy in 1894 resulted in the appointment to the faculty of Repin and other artists from the Association of Travelling Exhibitions, which had once been the voice of opposition. Repin had once dabbled with Impressionism, but he remained loyal to the Association’s entrenched realist methods. One portrait Werefkin painted of a Lithuanian Jew induced him to draw comparisons with Velázquez, and even to admit envy of her luminous technique, but his effusive praise only served to deepen her sense of despair. As a subscriber to all the latest art magazines from abroad, she was able to acquaint her circle of friends with the names of Manet, Whistler and Monet, further inciting their restless curiosity about developments outside Russia.

An opportunity to escape the stagnant pond of Russian artistic life arose when Werefkin’s father died in early 1896, leaving her with a substantial pension as long as she remained unmarried. This was not a problem for an unconventional woman who had painted herself androgynously wearing a home-made sailor shirt, paint- brushes in hand. She had an apparent revulsion towards sex, stemming from her experiences assisting a country doctor in caring for hundreds of village women who were suffering the consequences of the crude male predatory behaviour she routinely observed. So Werefkin subli- mated her desires into an all-consuming dedication to art, which she persuaded her impecunious common-law spouse Jawlensky to share. The couple decided to plunge themselves into the vortex of cosmopolitan modern ideas swirling around Europe by moving to Munich, which had long been Europe’s most important artistic centre after Paris. In the 1890s the city’s lively cultural scene made it a mecca for writers and musicians such as Thomas Mann and Richard Strauss, while the community of more than a thousand full-time painters and sculptors attracted a constant stream of foreign students to its Academy and private art schools. The foundation of the Munich Secession in 1892 had only added to the city’s cachet.

Autumn (School) (1907), Marianne Werefkin. M. Werefkin Foundation, Ascona

Taking a cook and a young servant girl with them from Russia, Marianne von Werefkin and Alexej von Jawlensky, as they now styled themselves, settled in two adjoining flats in the bohemian quarter of Schwabing, turning one into a studio. From there it was only a 10-minute walk to the private art school set up in 1891 by the Slovenian artist Anton Azbe, where Jawlensky enrolled, along with several other Russian expatriates, including Kandinsky. After completing a portrait of Jawlensky soon after they arrived in Munich, Werefkin herself now stopped painting completely. Instead she sacrificed her creative energies to supporting and furthering Jawlensky’s career, believing fervently in his genius. She would not paint again for another ten years, but this was far from a fallow period for her. In 1897 she accompanied Jawlensky, Azbe and two Russian artist friends on a momentous trip to Venice, began to explore theories of colour and formed a new incarnation of the early 19th-century Lukasbund (Brotherhood of St Luke), intending to emulate its quest to restore spiritual values to art. Werefkin created a hospitable Russian atmosphere in their new home, complete with samovar, making it a magnet for diverse members of the large expatriate community in Munich, from diplomats to ballet dancers; but she also established a salon which acquired renown as an uncompromising forum for the exchange of progressive ideas.

In 1899, on one of her regular long trips back to Russia, Werefkin no longer had any compunction about infuriating her former teacher Repin by promoting what he perceived as Western decadence. Two years later, as she slowly formulated her new worldview, she began writing an unusual diary in French, in which she combined deeply personal reflections with ecstatic meditations on the creative principle, identifying it with the divine. Art is the cherished ‘stranger’ addressed as a lover in Werefkin’s remarkable Lettres à un inconnu; it is a tragic irony that while she rejoiced in her chaste relationship with Jawlensky at the beginning of her diary in 1901, seeing it as an expression of her artistic ideal, in real life he was forming a relationship with their 20-year-old servant girl, Elena Neznakomova. The Werefkin household spent the summer of that year in Russia as usual, but then found themselves immediately retracing their steps in the autumn when it transpired that Elena was pregnant. At the end of 1902, when the potential for scandal had blown over, the ménage à trois finally returned to Munich, but with little change to their domestic arrangements. Jawlensky’s son, born the previous January, was presented as his nephew, and Neznakomova continued to wait at table.

Werefkin somehow managed to overcome her deep sense of betrayal and forgive the man she had regarded as her soulmate, and in 1903 and 1905 she and Jawlensky made two important trips to Paris, where Gauguin and Van Gogh’s treatment of colour made a particularly deep impression. In 1905, sensing that she had now fully articulated her new artistic credo, she also brought her Lettres à un inconnu to a conclusion. When she returned to painting in 1907, she was no longer the ‘Russian Rembrandt’ touted by Repin who sought to imitate nature, but an emerging Expressionist artist committed to expressing ‘that which does not exist’. Through her wide reading of the literature and religious philosophy of Russian Symbolism, Werefkin had come, like her contemporary, the composer Alexander Scriabin, to a theurgic belief in art’s capacity to transform life itself, bringing humanity into contact with the divine. The fundamentally mystical outlook she developed was concentrated not on seeing or thinking, but on feeling. Werefkin regarded emotion as the driving force behind creation, and the key to expressing the transcendent spiritual reality lying beneath the banal surface of daily life. Beginning with works like Autumn (School) of 1907, the figures and representational details in her striking new visions of modern life, painted mostly in tempera rather than oils, were radically simplified. Having become a fervent believer in the autonomy of art, Werefkin now began an intense exploration of non-naturalistic colours, shapes and forms as a means to express her world view.

Self-portrait 1 (c. 1910), Marianne Werefkin. Lenbachhaus, Munich

Werefkin’s most productive period began in 1908. After four years away, Kandinsky returned to Munich with his former student and now partner Gabriele Münter, and they formed a close partnership with Werefkin and Jawlensky, spending three crucially important summers with them in the Bavarian village of Murnau. This was the time when Werefkin’s so-called Pink Salon was at its most vibrant and guests could almost feel the force of her extraordinary intellectual energy. It was Werefkin who instigated the discussions that led in 1909 to the four friends becoming founding members of the Munich New Artists’ Association (Neue Künstlervereinigung München), with which they aimed to promote work that other institutions in the city found unacceptably modern. Münter, 17 years younger than Werefkin, was clearly rather intimidated by the imposing ‘Baroness’ (as she was nicknamed in a nod to the titles of the Baltic nobility). She painted Werefkin in 1909 wearing one of her signature flamboyant hats, which she described looking like ‘a wagon wheel, with all manner of things piled upon it’. Werefkin herself painted a famous self-portrait in a hat the following year, giving herself scorching red eyes. Like Kandinsky, she and Jawlensky still maintained close connections throughout this time with Russia, where the artistic scene since the 1905 Revolution was becoming increasingly dynamic. As well as making regular visits, they sent work to progressive exhibitions held in St Petersburg, Odessa and Kiev, and also to the first infamous ‘Jack of Diamonds’ exhibition, which formally launched the young Moscow avant-garde. Werefkin was one of only five female artists represented, along with her younger Russian contemporaries Natalia Goncharova and Alexandra Exter, and Erma Bossi and Gabriele Münter from Munich.

In 1912 Werefkin exhibited 43 works at a gallery in Wuppertal, where they were hung next to paintings by Munch, whom she revered; in 1913 she received the distinction of being included in the First German Autumn Salon at Herwarth Walden’s gallery Der Sturm in Berlin, commonly regarded as the most important exhibition of modern art in Europe before the First World War. In early 1914 she travelled back to Russia to stay with her brother, now governor general of Vilna, and gave a lecture at the city’s art school in which she defended her deci- sion not to follow Kandinsky into abstraction. Following the example of all greats of the past, she argued that ‘one must have one’s feet planted firmly on the ground in order to move forward. We therefore do not deny life, do not depart from it.’ Life naturally became difficult for Werefkin and Jawlensky immediately following the outbreak of war, which forced them into exile in Switzerland. The Revolution brought the abrupt cessation of her Russian pension, and five years after that came the final ending of her fraught relationship with Jawlensky. Although Werefkin no longer lived in a Russian milieu, and as an Expressionist artist continued to produce work of a cosmopolitan modernist character with no nationalist allegiance, she nevertheless remained true to her roots. She maintained close contact with those members of her family who lived in emigration, and shortly before her death in 1938, she was given extreme unction by Ivan Kurakin, a former fellow member of the Russian nobility who had become a priest. Werefkin was buried according to the Orthodox rite, to the sound of Russian funeral bells. It is striking that when Stefan Zweig met her at the end of her life, he perceived her as someone ‘Russian to the depths of her being’.

From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.