The French revolution cut Louis-Léopold Boilly’s career into two distinct halves. He was born in 1761, in a small village near Lille; in his twenties, he set off for Paris, where he died in 1845. Here he established himself as a genre painter of the kinds of slyly erotic scenes synonymous with older artists like Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) and François Boucher (1703–70). In Comparing Little Feet (c. 1791), which opens this small but illuminating exhibition, two young women are at once intent on the size of their delicate appendages and oblivious to the gaze of the viewer, who is thereby freed to savour both careless décolletage and rounded thigh. The prurient focus is never in doubt, but Boilly lavishes an equal, almost perverse, care on the still life behind them: a glass bottle, a silver tumbler, a guitar. This gleeful combination of immaculate surface and seductive subject, drawn at once from the French rococo tradition and the work of the fashionable Dutch fijnschilders (literally ‘fine painters’) ground to a halt in 1794, when Boilly was denounced to the Committee of Public Safety by a rival for producing works contravening the morality of the new Republic.

Comparing Little Feet (c. 1791), Louis-Léopold Boilly. The Ramsbury Manor Foundation. Photo: © the trustees of the Ramsbury Manor Foundation

However, as this exhibition spanning genre, portraiture and urban life makes clear, Boilly was peculiarly adaptable. Shortly after his denunciation, he produced the sycophantic Triumph of Marat and, in 1798, his definitive portrait of the new France, The Meeting of Artists in Isabey’s Studio. Part conversation piece, part history painting, it unites the portraits of 31 artists, sculptors, engravers, performers and men of letters, in the studio of the titular miniature painter. This space, more elegantly classical than artistically disarrayed, is a space of masculine intellect and creativity. One critic complained of visitors to the Salon ‘lay[ing] siege to this picture’. The focus of popular attention was Boilly’s skill in capturing a likeness, but the critic highlighted an association that would become increasingly important, between Boilly’s work and the Parisian crowd.

If Isabey’s Studio is an immaculate, frieze-like arrangement of a crowd of contemporary artists, the later work Carnival Scene (1832) is a Hogarthian tumult of men, women and children from across the social spectrum, interwoven with costumed figures from the commedia dell’arte. Here and elsewhere, Boilly is intrigued by odd juxtapositions – those moments when disparate urban types might come together – and by how the city mediates those interactions. Fashionably dressed bourgeois mingle with working-class families and street urchins to watch a puppet show in The Poor Cat (1832). The hand thrust out to a family for payment in To Pass, You Pay (1803) is a brasher equivalent of the collection dishes held up by the children manning the titular homemade shrine in its pendant, The Little Chapel (c. 1803–04). In The Barrel Game (c. 1828), two men come together to share a light, and a grenadier embraces a young woman, while the men playing the game of the painting’s title strain to hit the table top at the other side of the composition.

The Meeting of Artists in Isabey’s Studio (1798), Louis-Léopold Boilly. Musée du Louvre, Paris Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux

Although in these paintings the crowd ebbs and flows in seeming hurly-burly, surface is still very much at issue, both in the tightly controlled, miniaturistic handling of paint, and in the figures themselves, many of whom are masked. It was Boilly who originated the term trompe l’oeil , which he gave as the title to a painting (now in a private collection) sent to the Salon of 1800. The current exhibition represents his visual trickery through works such as A Girl at a Window (after 1799), painted in grisaille to resemble an engraving. There is a peculiar irony to the idea of making a singular work of art resemble a mechanically reproduced print; it calls attention to Boilly’s conception of the modern artwork as a commercial object designed to circulate through the urban crowd, to be bought and sold, re-displayed and reconfigured.

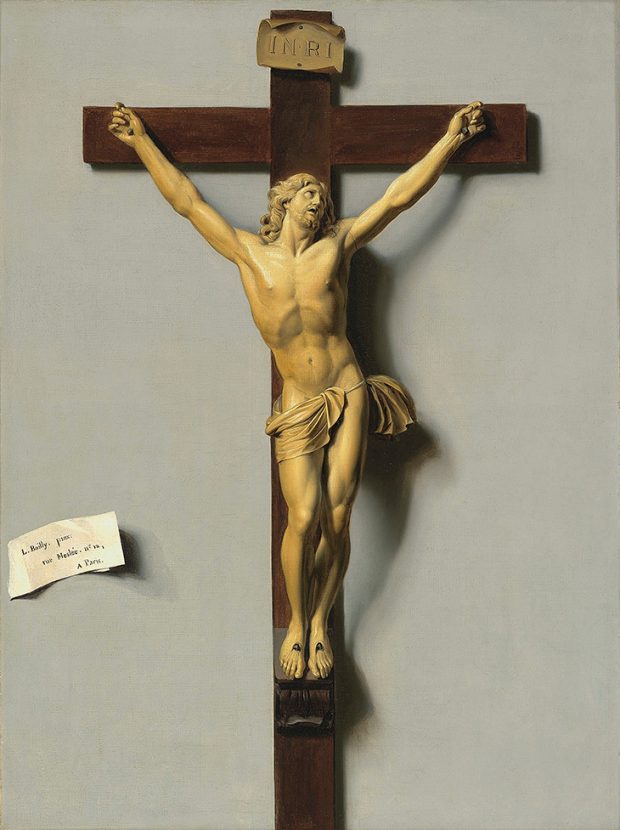

Boilly achieved significant critical success but seems always to have measured his own success in financial terms. At the end of his life, he claimed to have produced 5,000 portraits of bourgeois sitters, all in the same 32 x 17cm format – each, he claimed, dashed off in a mere two hours. The charismatic little canvas of the Comtesse François de Sainte-Aldegonde (c. 1800–10), displayed here, makes the volume of commissions easy to believe. But Boilly’s commercialism reaches blasphemous heights in this exhibition’s closing work, A Trompe l’oeil Crucifix of Ivory and Wood. The brushstrokes describe every material feature of the object, transforming a baroque ivory crucifix into a modern still life object. The traditional ‘INRI’ is complemented by a brazenly self-promoting painted cartellino: ‘L. Boilly pix: rue Meslée, no 12, À Paris’.

Trompe-l’oeil Crucifix of Ivory and Wood (1812), Louis-Léopold Boilly. Jean-Luc Baroni, London. Photo: courtesy the owner

‘Boilly: Scenes of Parisian Life’ is at the National Gallery, London, until 19 May.